Landmarks

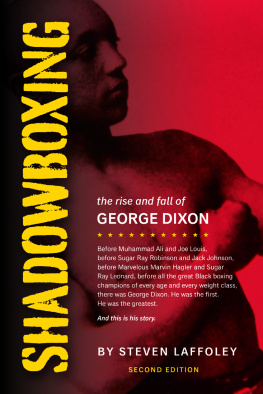

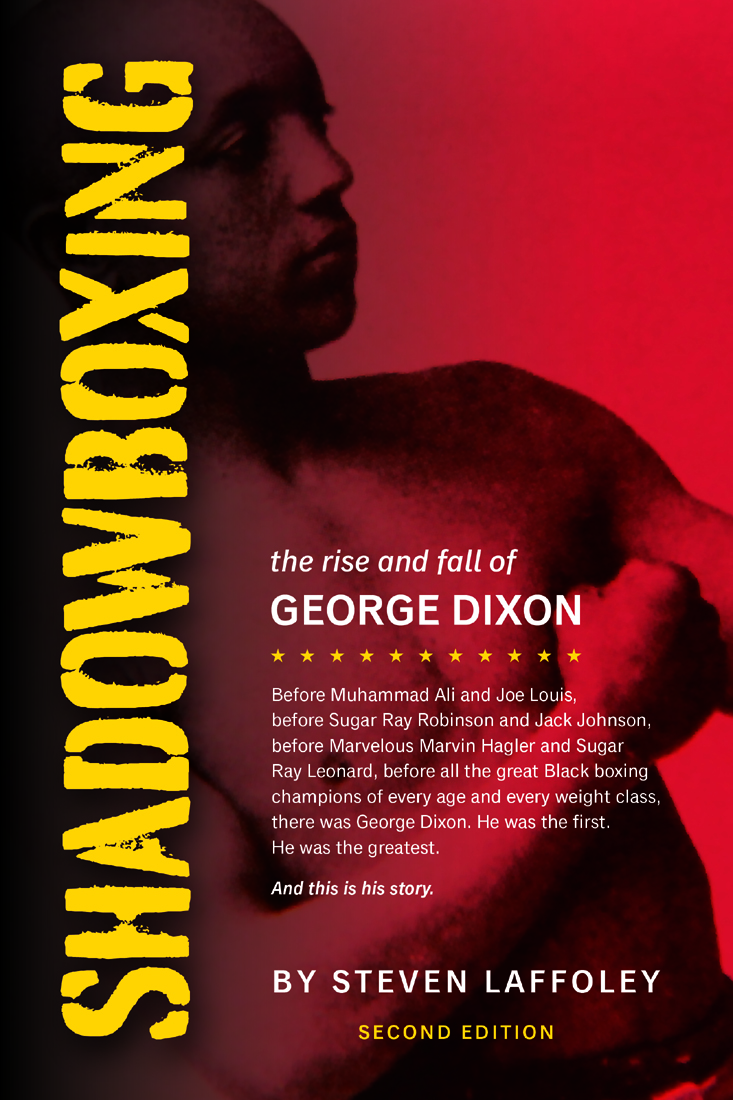

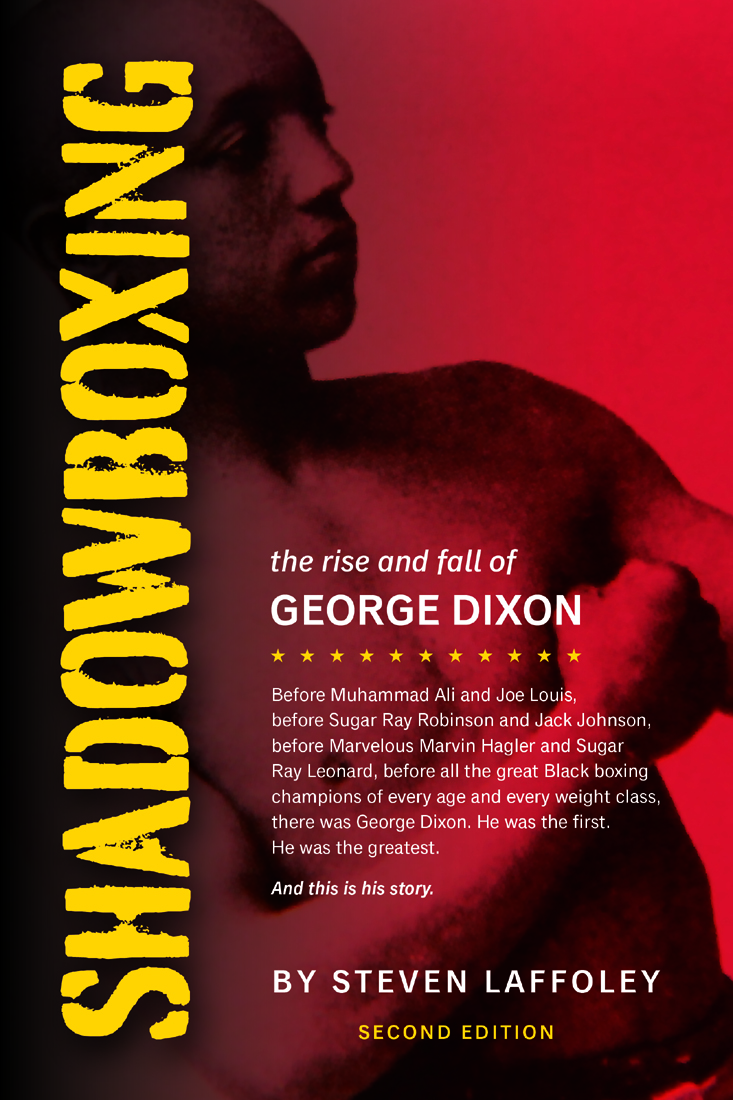

Shadowboxing

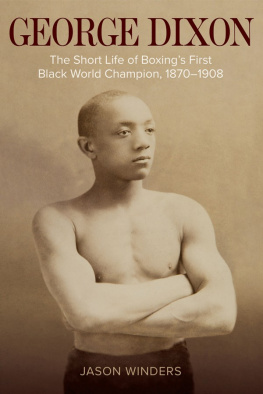

the rise and fall of George Dixon

Second Edition With an Afterword by the Author

Steven Laffoley

Pottersfield Press, Lawrencetown Beach, Nova Scotia, Canada

Copyright Steven Laffoley 2022

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or used or stored in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or by any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any requests for photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems shall be directed in writing to the publisher or to Access Copyright, The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (www.AccessCopyright.ca). This also applies to classroom use.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: Shadowboxing : the rise and fall of George Dixon / Steven Laffoley.

Names: Laffoley, Steven Edwin, author.

Description: Second edition.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20220138796 | Canadiana (ebook) 20220138842 | ISBN 9781989725870 (softcover) |

ISBN 9781989725887 (EPUB)

Subjects: LCSH: Dixon, George, 1870-1908. | LCSH: Boxers (Sports)CanadaBiography. | LCSH: Boxers (Sports)United StatesBiography. | LCSH: African American boxersBiography. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC GV1132.D59 L34 2022 | DDC 796.83092dc23

Cover design Gail LeBlanc

Pottersfield Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada for our publishing activities through the Canada Book Fund. We also acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Province of Nova Scotia which has assisted us to develop and promote our creative industries for the benefit of all Nova Scotians.

Pottersfield Press

248 Leslie Road

East Lawrencetown, Nova Scotia, Canada, B2Z 1T4

Website: www.pottersfieldpress.com

To order, phone 1-800-NIMBUS9 (1-800-646-2879) www.nimbus.ns.ca

For George Dixon

Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness.

W.E.B. Du Bois

The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

W hat follows are reflections and renderings drawn from first-hand accounts and second-hand recollections. All words quoted originate in newspapers of the day. All fights described are drawn from ringside reports.

Contents

I used to be a good fighter, but I dont know what I am now.

George Dixon (1908)

A n hour before midnight, on January 5, 1908, a yellow Taximeter Cab clattered west along East 27th Street in Lower Manhattan to First Avenue, where it turned left and stopped near the heavy double doors of Bellevue Hospital. The cab idled roughly as the driver stepped down from his high seat and opened the side door.

Three men emerged.

George Dixon the negro ex-featherweight champion applied last night at Bellevue Hospital for treatment, New Jerseys Trenton Times would report the next morning. He was accompanied by a white man and a negro.

The two men with Dixon each held an arm as they passed through the entrance doors into the reception area. Inside, they approached a low, wooden admitting desk, where the nurse on duty was seated. The nurse looked up at Dixon. No doubt, she was distressed by what she saw. Dixons eyes were clouded, his face drawn, his skin pallid. She turned and reached for a registration form. As she did, the physician on duty, Dr. Ransom Hooker, glanced up from his desk.

He recognized Dixon.

George, he said, what are you doing here? Last time I saw you, you were up at the Long Acre Athletic Club, and you didnt look much in need of health then. Dixon knew the club well, a poorly lit, decrepit warehouse on West 29th Street where second-rate boxers fought in a makeshift ring for a few dollars a night.

To tell you the truth, said Dixon, his voice weak, Im down and out.

Dr. Hookers face betrayed concern. He stepped away from his desk and helped Dixon to a nearby chair.

Dixon breathed heavily as he sat.

John Barelycorn has got me, Dixon said, and I am suffering from rheumatism.

Dr. Hooker nodded. He turned and retrieved the admitting form from the nurse. Then he sat down and wrote Dixons name across the top. He reviewed the questions.

Who is your nearest friend, George? he asked.

Well, Dixon said, they are mostly all gone now. But the best friend I ever had was John L. Sullivan. Hes the only man that would let me have money when I wanted it. Sullivan had been the first heavyweight boxing champion and was possibly the only boxer more famous than George Dixon in his prime.

Hooker began writing Sullivans name, when Dixon interrupted. But he doesnt live here.

Dixon looked to the floor and fell silent.

George, Dr. Hooker asked again, who is your nearest friend in the city?

Michael Harris, Dixon said after a moment. 256 West 41st Street.

Hooker wrote the name and address.

And where were you born, George?

I was born in Canada, Dixon said, but Ive been here for thirty years.

And your age? Hooker asked.

Thirty-seven.

Dr. Hooker looked up and stared for a moment at the man sitting in front of him. Dixon, feeble and exhausted, looked much older than thirty-seven. Almost reflexively, Hooker offered Dixon a piteous smile.

And your occupation, George?

Dixon looked at his hands. They were swollen and sore. He made a fist of his left hand and turned it slowly. I used to be a good fighter, he said, then a teacher in boxing. He hesitated and his eyes filled with tears. He slowly looked up at Dr. Hooker. But I dont know what I am now.

* * *

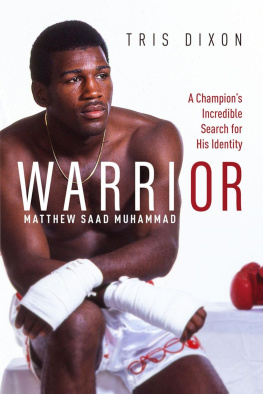

George Dixon was the finest boxer of his generation and arguably among the finest boxers ever. His accomplishments in the ring were extraordinary: the first Black boxing champion, the first Canadian champion, the first champion of multiple weight classes, and the first champion to lose and regain a title. In a twenty-year career, Dixon defended his title more than any other champion then or since and reportedly fought in an unprecedented eight hundred bouts.

Making these accomplishments even more astonishing was the context within which these achievements were earned. In an age when Black men were routinely lynched for simply being black, George Dixon publically fought and beat hundreds of white boxers across America, Canada, and Europe. He even married a white woman.

So, too, George Dixon was a great innovator. As much as anyone, George Dixon defined what we recognize today as the sport of boxing, introducing and refining many training and fighting techniques still used more than one hundred years later. Long- and short-distance running, the punching bag, shadowboxing, and any number of combination punches and defensive maneuvers the list of Dixons contributions to boxing is uniquely long.

Before Muhammad Ali and Joe Louis, before Sugar Ray Robinson and Jack Johnson, before Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Sugar Ray Leonard, before all the great Black boxing champions of every age and of every weight class, there was George Dixon.

He was the first.

And he was the greatest.

Renowned boxing historian and Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleischer once said of Dixon, For his ounces and inches, there never was a lad his equal. Even in the light of the achievements of John L. Sullivan, the critics of his days referred to Little Chocolate [George Dixon] as the greatest fighter of all time. I doubt there ever was a pugilist who was as popular during his entire career. [Dixon was] a marvel of cleverness, yet he could hit and slug with the best of them. He was fast, tricky, combative, canny, courageous, a master in every respect of the art of self-defense, a great ring general. His left hand was one of the best in the business. His double left to the body has never been equaled. His right was equally good.