Table of Contents

The One That Got AwayChris Ryan was born near Newcastle in 1961. He joined the SAS in 1984. During his ten years he was involved in overt and covert operations and was also Sniper team commander of the anti-terrorist team. During the Gulf War, Chris was the only member of an eight man team to escape from Iraq; three colleagues were killed and four captured. It was the longest escape and evasion in the history of the SAS. For this he was awarded the Military medal. For the last two years he has trained potential recruits for the SAS.He is also the author of the bestsellers Stand By, Stand By, Zero Option, The Kremlin Device, Tenth Man Down, The Hit List, The Watchman, Land of Fire, Greed, The Increment and Blackout , as well as Chris Ryan's SAS Fitness Book and Chris Ryan's Ultimate Survival Guide , published by Century.He lectures in business motivation and security and is currently working as a bodyguard in America.

Also by Chris Ryan Stand By, Stand By

Zero Option

The Kremlin Device

Tenth Man Down

The Hit List

The Watchman

Land of Fire

Greed

The Increment

Blackout

Ultimate Weapon Chris Ryan's SAS Fitness Book

Chris Ryan's Ultimate Survival GuideIn the Alpha Force SeriesSurvival

Rat-Catcher

Desert Pursuit

Hostage

Red Centre

Fault Line

Blood Money

Hunted

THE ONE THAT

GOT AWAY CHRIS RYAN

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.ISBN 9781409060321Version 1.0 www.randomhouse.co.uk

This edition published by Arrow Books in 20037 9 10 8Copyright Chris Ryan 1995Introduction Copyright Chris Ryan 2001Chris Ryan has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988 to be identified as the author of this workThis electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaserFirst published in the United Kingdom in 1995 by Century www.rbooks.co.uk Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British LibraryISBN: 9781409060321Version 1.0

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following:Duff Hart-Davis for all his encouragement, patience and valuable time that he spent on this project.All my family and friends for the patience and understanding they showed me throughout this whole adventure.My editor, Mark Booth and his team at Random House for their help and hard work.Last but not least, Barbara Levy, my agent, for pointing me in the right direction.

for Sarah

IN THE BEGINNING I believed,But found the time for doubting.He made no sound,I heard the Devil shouting.I wanted peace,I did not want the glory.I walked in Hell,And now I tell my story.I sing sad song,I did not write the music.I find sad wordsWaiting just inside my mind.I played my part,But seldom did I choose it.I held a gun,I did not want to use it.Call it fate or destiny

By either name, it troubles me.And now,If you should look into my eyes,

By chance you might just see

A sad, sad soul that sheds its tears,

Yet lets the heart go free.And in between the two of them

If you should read my mind,

You'll know the soul still sheds its tears,

For deeds left far behind.But if you see the eagle there,

Then don't ignore the dove,

For now that all the killing's done

There's nothing left but love.J. Miles

Glossary

| AWACS | Airborne warning and control system aircraft |

| Basha | Sleeping shelter |

| BCR | Battle casualty replacement |

| Bergen | Haversack |

| BG | Bodyguard (noun or verb) |

| Casevac | Casualty evacuation |

| CO | Commanding officer of the regiment |

| Comms | Communications |

| DF | Direction finding (equipment) |

| Director, The | Officer commanding Special Forces, generally a brigadier |

| DPM | Disruptive pattern material camouflage clothes |

| E & E | Escape and evasion |

| ERV | Emergency rendezvous |

| FMB | Forward mounting base |

| FOB | Forward operating base |

| GPS | Global positioning system (navigation aid) |

| GPMG | General-purpose machine-gun (Gympi) |

| Head-shed | Headquarters |

| Int | Intelligence |

| Loadie | Crewman on RAF military flight |

| LUP | Lying-up position |

| Magellan | Brand name of GPS |

| MSR | Main supply route |

| NBC | Nuclear, biological and chemical |

| OC | Officer commanding the squadron |

| OP | Observation post |

| PNG | Passive night goggles |

| PSI | Permanent staff instructor |

| REME | Royal Electrical Mechanical Engineers |

| Rupert | Officer |

| RTU | Return to unit |

| RV | Rendezvous |

| SAM | Surface-to-air missile |

| Sangar | Fortified enclosure |

| Satcom | Telephone using satellite transmission |

| Shamag | Shawl used by Arabs as head-dress |

| Shreddies | Army-issue underpants |

| SOP | Standard operating procedure |

| SP Team | Special Projects or counter-terrorist team |

| SQMS | Squadron Quartermaster Sergeant |

| SSM | Squadron Sergeant Major |

| Stag | Sentry duty |

| TACBE | Tactical rescue beacon |

| TEL | Transporter-erector-launcher vehicle |

| U/S | Unserviceable |

| VCP | Vehicle control point |

| Weapons |

| 203 | Combination of 5.56 calibre automatic rifle (top barrel) and 40mm. grenade launcher below |

| .50 | Heavy machine-gun |

| 66 | Disposable rocket launcher |

| GPMG | 7.62 medium-calibre general purpose machine-gun Minimi |

| 5.56 | calibre machine-gun |

| M19 | Rapid-fire grenade launcher |

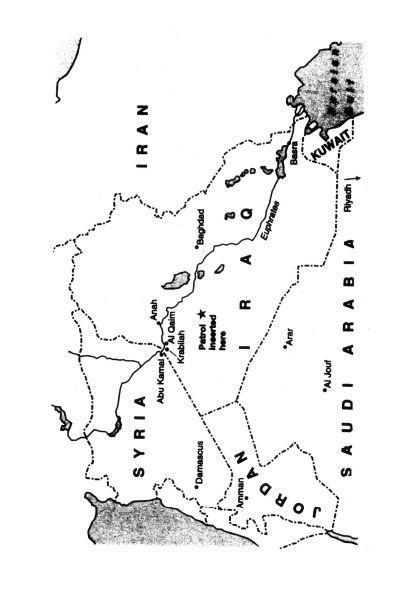

Introduction Ten years ago I walked out of the Iraqi desert. For the last two days of my escape, hallucinations of my two-year-old daughter, coming and going in waves, had given me the strength to carry on. Since then, back in England, I've sometimes been more lonely than I was in the desert, but it's still the thought of Sarah that pulls me through.I know it sounds daft, but when I think back to those seven days and seven nights, the first thing I remember is the cold. When you're on an exercise, particularly in Wales up on the Brecon Beacons, the weather can get pretty foul, but you always know that if there's a risk of exposure, you can knock on a farmhouse door and you'll be given shelter.In the Iraqi desert there was no hope of relief.When I was hidden and should have been able to relax a little bit, it was worse. Because I was stationary I was not generating any body heat and so became more prone to hypothermia. When sheer exhaustion overtook me, I would be woken almost immediately with my body convulsing in uncontrollable shivers.But even then I was coping because I knew what I had to do. Although I had nearly reached the limits of my endurance, both mental and physical, I didn't go over the edge. I stayed alert. I avoided capture. I made the border and I crossed it. Paradoxically, the real problems for me started when I was over the border, in Syria and safe.What happened then seems like a bad dream. There were none of the feelings I expected, such as relief or exhilaration. I wasn't even sure that I was in Syria for a while. When I found a house belonging to a poor peasant family, I had to contend with an old man trying to get his hands on the gold coins we were given to bribe our way out of trouble not the reception I was hoping for. The driver who gave me a lift to the nearest town told me that it was a bad war and I shouldn't be there. Once in the town, I found myself being chased down the street by a lynch mob. I was shuffling like a geriatric and it was just by luck that I was able to duck into a police station. Even there the atmosphere was ultra hostile. Uniformed and plain clothed security police rifled through my kit before dressing me in Arab clothes and driving me off into the desert. There we rendezvoused with a Mercedes full of Syrian secret police who first of all threatened to drive me back to Baghdad, then staged a mock execution, blindfolding me, making me kneel and putting a gun to the back of my head.In retrospect I can see what was happening. Syria might have been a member of the Gulf War coalition, but for years the government had been feeding its people a load of anti-western propaganda. What's more, the people clearly did not like the idea of British soldiers killing their cousins just over the border.All through my escape, following Standard Operating Procedures had given me a sense of purpose and reinforced the sense that I was doing a good job. As soon as I was on safe ground, I let my guard down and control slipped out of my hands. I lost all sense of proportion and could not shake off the sense of danger. By the afternoon and into the evening, I still hadn't slept. Safe in Damascus, the Syrians had me fitted with a new suit and shoes. That just sparked off a fit of paranoia; I was terrified that they were going to parade me in front of a press conference and I would be revealed as a member of the SAS. Basically my mental circuit board had overloaded and was knackered.As well as being a nervous wreck, I was a physical one as well. I had lost thirty-six pounds in weight towards the end of the walk my body had been feeding off itself to keep going. My gums had receded so far that the roots were exposed, making me look like a vampire. Every time I chewed, my teeth wobbled and the gums bled, so with every mouthful I was tasting my own blood. For years afterwards I couldn't look at a rare steak without feeling sick. My feet were shot to hell, my fingernails were floating on pus, and my mouth was burning because I had drunk effluent from a yellow cake processing facility.When I got back to the Regiment, everyone started slapping me on the back, and saying that it was the longest escape and evasion in SAS history. My attitude was simply that escape and evasion was something I had been trained to do. I had followed SOPs and they had worked. End of story. So when I was asked to talk about it, I did, but all the time I was wondering why. I just wanted to get back to soldiering. When they offered me the chance to go home, I refused and said that I wanted to get stuck in again. That response was nothing to do with bravery or a sense of duty. It was to do with losing a grip on reality.Eventually I did get home. It was a fine day blue skies, a few high clouds. The minibus drew up in the quadrangle at headquarters where Jan, my wife, was waiting for me. I saw her but instead of hugging her or anything, I told her to wait while I went off to see the doctor. She insisted on coming in with me to find out what my real condition was. She was sick with worry because the SAS rumour mill had been in full swing, and, according to the Chinese whispers, I was radio active and had lost my teeth and hair. In the doctor's surgery whenever she tried to hold my hand, I kept pushing her away. All I wanted to do was play everything down. I told her it was no big deal, I was just back from a job. That night I did tell her about the escape but my attitude was still: what's the fuss about?Things went from bad to worse. We went away for the weekend and all I could think was that I'd rather be anywhere else. At home, I didn't even want to have anything to do with my daughter Sarah. As I say, in the desert it had been visions or hallucinations of her that had got me through the roughest patches and sent me on my way to the border. Back home, none of that seemed to matter. I went from not wanting them around, to wishing they would get out of my life, to actually coming close to hating them. I didn't shout. I wasn't violent. I was just nasty. If I came home in a bad mood and Jan had cooked tea for me, I'd say: I'm not eating this crap, and go out drinking with the lads. If Sarah wanted to play, I couldn't handle it and just pushed her away. It was frightening; the feelings just crept up on me.As far as the Regiment was concerned, this was business as usual. The divorce rate in the SAS is astronomical and your mates aren't going to take you to one side and tell you you're neglecting your family. Even so, the Sergeant Major saw I was acting strangely and told one of my mates, Kevin, to keep an eye on me. Naturally, Kevin let me know straight away. But now I had paranoia to deal with as well. Because I felt that people were watching me, I felt I had to prove more than ever that I was the soldier I used to be and I drove myself to show I wasn't cracking up. Of course it all came out somewhere and, once again, my wife and daughter had to take the strain. Being deployed on an operation in Zaire was a relief.In retrospect it was the worst thing I could have done and things could easily have gone pearshaped. I was like an unstable bomb ready to go off at any time and nearly did. In the book I describe how a little incident at the airport a stroppy customs official trying to get heavy with some harmless clay masks I had in my suitcase brought on a full-scale, uncontrollable panic attack. What I didn't go into then were incidents far worse than that.To say it was hot in Zaire doesn't describe half of it. For the most part the skies were overcast, the atmosphere heavy and oppressive, the air hazy. The capital seemed to be crumbling. We got our food from a supermarket down the end of an old dirt track. All the buildings, it seemed, were run-down it didn't matter whether they were the old colonial ones or the modern concrete boxes. Half the shops were closed; people brought stuff in from the shanty town or the countryside outside and sold it on blankets by the road.We were tasked initially with evacuating the embassy staff to Brazzaville, just across the border in the Congo Republic. However, shortly after we got there the mission changed to ensuring the embassy was secure, defending it if necessary, bodyguarding the British ambassador, and planning and securing his journeys. It was a nervy time for two main reasons. The situation on the ground was highly volatile. Basically the Zairean army wasn't getting paid and the soldiers went on a rampage of looting whenever they felt like it. All the other nations had pulled their embassies out of the country even the South Africans were laughing at us for staying.The second reason was the equipment we were given. When the job had come up, we had done an appreciation of what was needed: landmines, Claymores, 66 Rocket Launchers, Gimpies, pistols and boats. Instead we were just given a pistol each and an MP5 sub-machine-gun. For me, this brought back the nightmare of the Gulf. Now, it's true that no one can beat the SAS, or the British Army in general, at getting the job done and improvising with the tools available. Time and time again we pull the rabbit out of the hat. But that's no reason for deploying troops with inadequate equipment. It had gone wrong in Iraq, the patrol had been compromised and men had died because we had the wrong equipment. In Zaire I could feel the whole history repeating itself around me and maybe that triggered fears, deep down, that we were going to be left high and dry again. I started to act strangely.There was a diamond trader out there quite respectable, not a rogue by any means and he got pretty friendly with us. He was buying from the mines then bringing the uncut diamonds back to the city. He told us all about it, probably thinking he could trust us because we were a professional outfit working for Her Majesty's Government. The long and short of it was that I remember sitting down with the lads and saying: 'Let's do him. We'll wait until he does a big buy and then we'll do him.' Of course we didn't, but I had it in my head.A lot of the time during that posting I was having waking hallucinations. I would be looking at one of the guys and suddenly a bullet hole would appear in the middle of his forehead, and half his skull would shatter and disappear. It all happened silently, like in a dream. I wanted to tell my mates what was happening, but I knew I couldn't I guessed what their reaction would be. I started to think that maybe I could see the future and that I was foreseeing all our deaths.As the situation in Zaire went critical, the expat community started to pull out and the embassy staff was slimmed down. That left a lot of dogs around, household pets that people couldn't, or didn't want to, take with them. I don't know how it started but suddenly I became the solution to this problem. People started bringing their dogs round to the embassy and asking me to deal with them. I knew what they meant they wanted them put down so I dispatched them. In the normal run of things I love dogs and the real me would have been telling these people to sling their hooks and face their own responsibilities. I would not have been digging holes, shooting the poor bloody mutts and burying them.It was while we were planning one of the ambassador's journeys that the most frightening thing happened. During the recce we passed a market. I asked my mate Dunc, who was driving, to pull in. On one stall was a wooden carving of a man sitting down holding a stick. I saw it and thought: I've got to have this. So I started bargaining with the stallholder. I got the price down a bit, then realised I'd come out without any money, so I told the guy that I'd drive to the embassy, pick up my money, come back and collect the carving. But he was so desperate to make the sale, he asked if he could come with us to the embassy and wait outside while I went in and got the five dollars. We said it would be fine, he got in and we started on our way back.The road back to the embassy ran alongside the Congo river, which is very deep and very fast, and there was only a narrow strip of land between us and it. Suddenly I thought: I'm not going to pay this man for the carving. So I put my hand on my pistol and said to Dunc: 'I'm going to shoot this bastard and throw him in the river.'Without batting an eyelid Dunc said: 'It's going to make a fucking horrible mess and there's no way I'm going to help you clear it up.' Right then I had one of my hallucinations. I saw a bullet go into this guy's head, I saw the door stanchion and the window covered in blood and brains and bone fragments, and I thought: 'He's right. I can't be dealing with all that.' When we got to the embassy, I went inside, picked up the money, and gave it to the guy. He handed over the carving and legged it down the road. It was then I realised that he spoke English and had understood every word I'd been saying!After Zaire it was off to Buckingham Palace for the medal. A dreadful day. Jan and I were not talking. It felt like the whole day was spent in silence. I couldn't see why I was being singled out, or the other guys from Bravo Two Zero for that matter. There were soldiers who'd stayed more than 40 days behind enemy lines, taken part in big actions and done a lot of real damage. They didn't get medals. Stan didn't get a medal, Dinger didn't get a medal. As far as I was concerned, the bravest man in B squadron was the commander of one of the sister patrols who'd aborted the mission as soon as he saw the real conditions on the ground no cover, nowhere to establish an OP and almost no chance of doing damage to the enemy without risking everyone's life. In the Regiment it is carved in stone that the man on the ground makes the decisions but it's typical of the whole mess that the patrol commander was hauled over the coals. His career has suffered as a result of doing the right thing.Four months later, the situation with Jan got so bad that we separated. I stayed in Hereford; she took Sarah off to Northern Ireland to be near her parents. We had to mortgage ourselves up to the eyeballs and our finances were so tight that she kept having to call me up for extra money a new pair of shoes or clothes for Sarah. I even resented her for that.What was happening to me? The current phrase is Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Before I went to the Gulf, if someone had said they were suffering from stress, I would have told them to get a grip and move on. The Regiment is terrified of becoming like the United States Delta Force where the men have to fill out forms about how they felt after every exercise. While I wouldn't want things to go that far, the attitude here is that if you let the shrinks get one foot in the door, you'll be Deltafied. It just isn't British. So while I was quite happy to admit I'd broken down and cried several times during the escape, and even that it had helped me, my attitude was: 'That's finished, now let's crack on to the next thing.'What I still think is that whatever stress you've been under, how you react to it will depend on the sort of person you are. If you've got a weak side, a selfish side or a dark side, that's going to come out, the same way it does when you're drunk. You have to confront it and not use the trauma as an excuse.People with strong belief systems cope with battle, fear and torture better than people without them, and it's possible I would have dealt with my stress better if my confidence in the Regiment hadn't taken such a knock. The SAS is supposed to do two things really well: getting the job done and looking after its own. With the Bravo Two Zero mission it failed on both counts. The intelligence was rubbish no patrol could have succeeded with the information we had. The radio frequencies we were given would have worked in Kuwait but we were a long way from there. The TACBEs were designed to reach AWACS planes up to 75 miles away, but they had forgotten to tell us that there were no AWACS within 300 miles. Needless to say, no one had told the AWACS control centre either. It's even possible that HQ did hear one of our requests to get lifted out and ignored it. All this was churning around in my head and needed an outlet, but the Regiment is simply not set up to deal with psychological fall-out after an action. In fact I'd say it doesn't give a damn. To be fair, I bought into this attitude.I remember hearing a radio programme in which explorers and mountain climbers people who could push themselves to extremes said that they'd been bullied as children. It rang a lot of bells. I'd had the crap kicked out of me for three years at my school and I spent my days wondering if I was going to get set on that day, and if I was, how I could escape getting hurt. It used to happen by the school gates, and people would wait there to see me getting beaten up.When I joined the TA, part of the reason I worked so hard was to get away from the old me the one that got pushed around. I found the harder I pushed and the more I achieved, the greater the distance grew between the new me and the old me. I took up judo and found out two more things. Firstly I could look after myself. Secondly the fear of getting hurt was far worse than the hurt itself. When I met those bullies again, and I did, it was me who had the upper hand. I knew that if they came at me I could drop them, so I started goading them. I felt different powerful and ten feet tall. In other words I had become a bully myself.That side of me came out under stress. Basically, I was throwing my weight around, challenging people to have a go at me so I could drop them when they did. But, thank God, I had learned something else: if you need to change, you can. It was up to me to do something about it. No one else could.After Zaire I was posted to the Training Wing, selecting and training potential SAS members. This was probably the best move for me. I couldn't have handled more active assignments. I was always on a knife-edge of violence, until something happened that changed me back to an approximation of my old self. The memory is very vivid and clear. I was on jungle training in Brunei. It was morning, I had just woken up and was sitting on my A-frame, having a brew with John best man at my wedding and my daughter's godfather.Suddenly it was as if I had been right down in a foggy valley for a very long time and now I was up and out of it and in the sunlight. I saw with complete clarity how I had been with everyone for the last year. My reaction was to put my head in my hands and say: that wasn't really me. It was like remembering a drunken evening and realising you've been a complete idiot, except in this case it wasn't an evening but a whole year. John said he'd been trying to talk sense into me all that time but I hadn't been listening. The worst of it, as far as I was concerned, was that I had effectively deserted my daughter. Immediately I set about trying to make that right. Although my relationship with Jan had taken a hell of a pounding, she moved back and we began to try to stitch things back together.I started seeing a lot of things in other areas of my life more clearly. Professionally, my career as a soldier was beginning to level out and a few things happened that made me realise it was time to move on. Firstly, after I came back from Brunei I broke my ankle in a freefall accident and the doctors said that my days of running around with a Bergen were numbered. Secondly I began to have doubts about the selection process. As a selector, there are rules to follow and standards to meet, but basically you have been through it all before and are looking for certain qualities. There's an unbroken line, a tradition that runs through the Regiment that is about finding a balance between being cut throat and a good team member, as well as having deep reserves of initiative, determination and single mindedness. My worries were that those qualities were being diluted by two factors. Firstly, I saw a good officer being failed because he was too young. I don't know whether it was professional jealousy or a sense of just being hidebound, but as far as I was concerned he should have been in. At the same time there were other cases where the Regiment seemed to be playing the numbers game overlooking shortcomings in some recruits because it was short of manpower.Whether my judgements were right or wrong, it was clear I was out of step with the whole set-up.Another factor came into play when a young lad I had passed into the Regiment was killed in Bosnia. He was a good soldier I'd seen him under pressure and I knew how hard he worked. What was significant about this was the way it hit me I kept on thinking that if I'd failed him, he'd still be alive.In the SAS you have to give 100 per cent. Everything has to be black and white. You're not brought into a trouble spot just to be a presence or keep the peace. You are put there to sort out a situation quickly, and usually with violence. The SAS soldier does not think about death in any moral sense. For many of us, the opposite is true. You move heaven and earth to get into a situation where you can put rounds down. It's the reason you put yourself through selection. It's what you are trained to do.Losing your mates is a way of life, however contradictory that seems. The deaths aren't always on active service the first soldier I saw killed was during a training exercise in Botswana. The next was a guy I shared a room with. He'd been selected for mountain training and just before he went off I remember telling him how I wished I was going too. I put it out of my mind, but then bumped into someone from the Regiment at a petrol station who told me that my roommate and another guy had taken a 2,000-foot dive over a ledge. And that was more or less it. I heard it, I was shocked, then I adjusted and got on with my life. What else can you do? Between 1984 and 1995, 18 men from the Regiment were killed, a figure that's probably gone up to about 25 now. That's a high attrition rate, percentage-wise. There are not that many in the Regiment, even when it's up to strength. When I was young I just thought: it's not going to be me. It's going to one of those grizzled old veterans that I talked to in the mess people who'd seen action in Oman back in the sixties and seventies. Suddenly, I had survived long enough to be a veteran myself and I felt I had the devil sitting on my shoulder. I couldn't shake the thought that it was going to be me next, and when you've got that mindset, you can't give 100 per cent any longer.I knew that it was time to get out.Sometimes it seems that London is full of SAS guys looking for the big bodyguarding contracts the 1,000-a-day jobs. The joke is that about half of the men doing it aren't even SAS and there's no way of checking up. Because the Regiment is secret, there's no central registry. One bodyguard I know about claims to have been a major and has even awarded himself the MC. He was nowhere near the SAS, never won a medal as far as I know, but he still gets away with it.I found out pretty quickly that bodyguarding a businessman or a film star is very different from bodyguarding in the SAS. For a start you're not just a bodyguard. You're a companion, a driver or someone to fetch the kids' pizza. When you give advice, there's no guarantee that anyone's going to take it and, if you make a fuss, you're out of a job. It took me three months to realise that it's not a glamorous way of life; it's just boring. I worked solo for a shipping tycoon, then joined a team, then did a few more jobs, but it was always the same story. Whether I was training a local team to guard an oil depot in Africa or training a police unit in surveillance skills, whether I was living in a five star hotel with a Michelin starred restaurant or living rough in a camp in the bush, I felt frustrated. Very quickly I began to wonder if I'd done the right thing.Then I was approached by a TV company who wanted to make a film about the patrol and my escape and evasion. I said earlier how I'd never really seen the importance of what I'd done, and I still don't properly understand the fascination with Bravo Two Zero; the SAS has been in action all over the world and countless books have been written about it, by historians, journalists and former SAS soldiers. But I was steadily getting accustomed to telling my story admittedly to military audiences. Soon after I had come back from Iraq, I was called into the CO's office and told that General de la Billire, or DLB as he's known, wanted to include my story in his official history of the SAS's involvement in the Gulf War. It wasn't a good time for me to start bringing it all up again, but it was put to me that DLB was a general and if I refused 'it could be detrimental to my career.' Officers have a fine way with words.My story got a lot of publicity it was selected for serialisation in the Daily Telegraph and soon after that the television company approached me and I agreed to go and talk to them. That was the start of my new career, as a writer.We all met in the director's home in London. The way they put it was like this. They told me that they wanted to make a dramatised, realistic version of the story from my point of view. I thought that sounded good and when I ran the idea past the guys I was working with, they all agreed. When the time came for the screenplay to be written, I took two guys with me who had worked with everyone in the patrol and they put their views of the various characters down on tape. I wanted the account to be clear and objective.While the film was in production an endless process I wrote The One That Got Away. The book was a big success and a real education for me. For a while, life became a round of interviews, and I was naive enough to think that every book got this sort of attention. I was still a bit of a wreck staying in a hotel up in Liverpool before going on Richard and Judy I spent half the night trying to wedge the door shut with the wardrobe. That was one of the effects of being exposed and vulnerable night after night during my escape. I simply could not sleep unless my bedroom door was locked and barricaded.I was also naive about the tricks that interviewers use for example, getting you into the green room a couple of hours before you're due to go on so they can ply you with alcohol. Before one TV interview, the guy asked me if there was any part of my story I felt sensitive about, so he'd know to steer clear of it. I told him, gratefully, that I didn't want to go into one of the events on the march because it was still pretty raw. The next thing I'm miked up and he's sitting across from me. While I'm still trying to get over the fact that he's wearing more make-up than Barbara Cartland, the first question he hits me with is about this exact thing!For the most part, the book was very well received. People bought it and no one from the patrol had any problems with the way I described events. With the benefit of hindsight I would have written some things differently I come across as more cocksure than I would like and I could have written about some incidents in ways which would have softened the impact on other people's feelings. Perhaps I took a bit too much for granted about how much every person in the SAS has a strong, basic respect for every other person in the Regiment, for example but there was no adverse reaction. It was when the TV film was broadcast that the shit hit the fan.When the producer and director had told me that they wanted to present my story as a true, dramatised version, what I never realised was quite how wide the gap can be between truth and drama. The problem is, once a TV programme's out there, the memory sticks. What's more, people assume that I OK'd it, when the opposite is true. I was credited as the military advisor, and on my visits to the set in South Africa I spent most of the time arguing with the way that events were being presented. After the film was shot, I was promised time in the editing suite which somehow never materialised. The version seen on the screen may have been dramatic but it wasn't the truth as I saw it. I know the TV film hurt some people pretty badly, and I'm sorry about that. I was asked to tell my story and did. I never thought it would be taken out of my hands in that way.There's a myth that because we're members of a small, elite Regiment we all get on. That's not the case. Just like any walk of life, the important thing is not how much you like people, but how well you work with them. SAS soldiers are not selected for being nice guys they're selected for getting a job done.So on any mission you've got a group of strong-minded and independent guys united only by a common aim of killing the enemy. It's a fine balance: you've got to pull together, but ultimately it's what each individual brings to the party that will make the mission a success. When things go wrong, the best way of clearing the mess up is to give everyone the chance to say what happened from their point of view. That means things might not go wrong in that way again.Within the Regiment, debriefs are important, no-holds-barred events. They follow the same structure: the Officer Commanding runs through how the operation or exercise was meant to go down. Then it goes down the chain, with everyone putting in their bit. That's when it gets interesting. If there was a problem the OC will ask why it happened. Someone will point and say: Because he wasn't in the right place. That guy will come back: Well I wasn't there because I was held up by this joker. Then people start to swear blue murder and the arguments start. But at the end of the day, even though the hardest thing a guy from the Regiment has to do is admit they made a mistake, you'll get a pretty clear idea of what actually happened and the chance to learn from it.The system isn't foolproof. There was an action in the Gulf where a vehicle was giving covering fire to men on foot who were in contact with the enemy. As soon as the vehicle itself started to draw fire, the driver took it into cover. During the debrief the driver was actually accused of cowardice by his gunner, but that was all hushed up because medals were on offer and the squadron sergeant major didn't want anyone rocking the boat. Now you might ask: why drag it all up? But the point is that a soldier who cracks under pressure might do so again. Debriefs let you learn from mistakes in the cold light of day and make damn sure you don't repeat them.For reasons it's hard to get to the bottom of, there was no real debrief and no chance to thrash things out together after Bravo Two Zero. As a result the cloud hanging over the mission has never been dispelled. Mistakes were made all the way up the chain of command. Maybe too many people were threatened by a debrief?The official attitude to the patrol had always been a mess of contradictions. On the one hand, some members of the patrol were threatened with disciplinary proceedings when they came back to England; on the other, they awarded four of us medals and gave us all a 1,000 payment. What does that tell you? That they made a misjudgement in the first place then tried to make up for the error of their ways? Or that they realised that disciplinary proceedings might throw up a lot of uncomfortable facts? Then there are the books. You have senior regimental figures slagging us off for writing about our experiences, when we were actively encouraged to do so by the then Commanding Officer of the Special Forces, General de la Billire. Even Field Marshall Lord Bramall suggested I have a crack at it.Considering everything, it's not so surprising that so much controversy has surrounded the various accounts of the patrol. Those of us with a story to tell are pretty strong-minded, and the version of events each of us has is the one we want to stick to. Mind you, when they're not on active duty people in the Regiment are always having a go at each other. For example, men on anti-terrorist duties are put on the Two Pint Rule that's the most they're meant to drink in a night but it's fair to say that they don't always keep to it. If someone sees them, they'll wait until the Officer Commanding or Sergeant Major is in earshot before launching into some story about how they saw so-and-so the night before, staggering around town at two o'clock in the morning with a bird on each arm. It thins out the competition.So when Mark the Kiwi, a member of our patrol, says his new book will expose Andy MacNab for having a 'selective memory', it's par for the course. And when the book is blocked by an injunction in New Zealand, and his co-author Stan says in court that I made up some of the events in The One That Got Away, it's typical SAS behaviour. It doesn't matter that he had already been captured and was hundreds of miles away when these particular events took place. It doesn't matter that I persuaded the rest of the patrol not to abandon him in the wadi after he collapsed with dehydration, yelled at him when he wanted to give up, and urged him not to put his life in the hands of an Iraqi goatherd because he thought the lad had an honest face. This is just the way SAS guys are. Besides, he's got a book to publicise and wants to get his name in the headlines.But the most painful thing to deal with has been the flak I caught from Vince's family about the way I presented him. The first thing I want to say on the subject is pretty straightforward: they objected to the way he was depicted in the TV film, and so did I. That film has been an albatross around my neck and I wish it had never been made. The second thing I want to say is that Vince Philips was a sergeant in the SAS, which means he was an exceptional professional soldier and a man to be reckoned with. SAS sergeants are the most able soldiers in the best fighting unit in the world; I thought my respect for him on that score would be taken for granted. By a series of administrative errors he ended up in a situation he should never have been in. I repeat, that is no reflection on his abilities as a professional soldier even Roy Keane has to sit on the bench for the odd Manchester United match. Different people are selected for different missions and Vince ended on the wrong one. This is not just my opinion. It's written down in black and white in the secret, official SAS report which is signed off by the Commanding Officer, goes into the SAS Registry and becomes part of the regimental archive. In fact it's clear that Vince was transferred to B squadron because at the time we were not operational. We were a support unit to replace battlefield casualties from A and D Squadrons. The problem was, once the decision had been taken to send us operational, no one thought to move Vince on again. Maybe the people who made the decision didn't know about the state of affairs; maybe they didn't pick up on it; maybe they thought, wrongly, that he would shake down in his new environment. Whatever the case, it was certainly not the only mistake that was made, but as far as Vince was concerned, it was fatal.I can't take back anything I wrote about the patrol and wouldn't want to. It's the truth as I know it. What I can do is give more details. We had lost contact with the rest of the patrol and spent the night in freezing conditions that we were not prepared for. With Stan coming out of severe dehydration and Vince feeling the cold worse than either of us, it was up to me to lead the patrol. My cold weather training in Bavaria should have been enough to teach me that, if someone is going down with hypothermia, you tie them to you. But I didn't. If I'd been up a mountain in deep snow, I would have done, but we were in the middle of the desert and cold was the last thing we were expecting. On top of that, there were so many other things to think about. We were trying to navigate by dead reckoning, with small scale maps that dated back ninety years, and stay on the alert for enemy contact. Of course in Escape and Evasion exercises you have always got to avoid contact, but for us it was doubly important. Our hands were like blocks of ice and we couldn't have used our weapons effectively. If we had come across any of the enemy, or even been spotted by them, our choices would have been stark: surrender or die.Though not suffering as badly as Vince, Stan and I were probably hypothermic too, and the reason we didn't go down like Vince could be a matter of any number of factors. Stan was wearing thermal underwear the reason he'd dehydrated earlier and that must have staved off the worst of the weather. I was carrying a lot of muscle, which probably helped me. It's been said that Vince should have been in better shape than either of us because he was a marathon runner in prime condition, but that doesn't save you from the cold. If anything, the very fact that he didn't have an inch of spare flesh meant he lost heat quicker than either of us, and then had fewer fat reserves to draw on. As for the rest everything that went on in the wadi what can I say? The official report backs up everything I've written in the book. I'm sorry it may not be comfortable reading, but it must stand.When you're tasked with a mission in the SAS, you go in and do it. Now I look at the Gulf War and wonder at the way the world is. We were selling arms to the Iraqis almost up to the last minute. I'm sure our intelligence must have noticed Saddam's armies massing on the Kuwaiti border, but no one did a damn thing until he went in almost as if we were saying: They're just Arabs; we don't take them seriously. Now you look at the No Fly Zones and the sanctions, and wonder when it is all going to end. We won a massive victory in the Gulf and then mishandled the peace. The difference between me now and me then, is that as a soldier, I couldn't afford to spend time thinking about rights and wrongs. Older and wiser, you can't help but do it.The SAS has a problem in terms of its public profile. It's a victim of its own success. That's got nothing to do with my book, or Andy's. Ever since men wearing black balaclavas went through the windows of the Iranian embassy on Princes Gate, the SAS has been a celebrity regiment, and something the public feels good about. It's a funny old thing the most secret regiment of the British Army is also the most widely publicised.One thing I am certain of, though, is the quality of the British Army in general and our Special Forces in particular. I still get a kick from reading about the way the army handles itself. When I read about actions like freeing the captured platoon in Sierra Leone, my admiration is boundless.I miss it I miss the company and I miss the craic. All through this story, my daughter Sarah has been the most important figure in my life. More than anything else, the shame I felt at the way I had been treating her forced me to take a hard look at my life and move in a new direction. Now I listen to her if she tells me I'm away too much, I try and do something about it. It's a question of re-evaluating responsibilities.Sarah's twelve now. She's fearless and very competent, whether she's doing a bungee jump, putting her hunter through its paces or piloting my ultralight aircraft. She's drawn to that sort of thing and does it for the buzz, not because she feels she has anything to prove. When people ask whether I'd let a son of mine go into the Regiment, I tell them the truth: I've got a beautiful daughter with more balls than the average guy and she's cleverer than me. If she craves adventure, I'd like her to have a job that would give her the freedom to do what she wanted. If she wanted to go into the army or special forces, I'd say good luck to her, but advise against it for a number of reasons. I'm worried about the forces in general it seems that governments want to make the same rules apply inside them as should apply in the rest of society. I don't think that works. The single most important thing for soldiers is effectiveness; anything compromising that is wrong. Within the SAS, I'm worried that it's becoming a bit top heavy with officers. When it was set up, there were always going to be officers and ranks, but there was never meant to be any distinction between them in terms of respect. Officers had one role and were chosen for their ability to do it; the men had other roles and were left to handle the operational side. The regiment was more or less run by the RSM and the SSMs and they formed a bridge between the soldiering skills of the NCOs and the more tactical skills of the officers. As long as a balance is maintained, the system works. But as soon as the Ruperts get the upper hand and that's what is happening now the NCOs are being told what to do by people with less operational experience and lower levels of soldiering skills than them. And that won't do.I'm not part of the SAS now; I'm a father with all the responsibilities and rewards. We like to keep a low profile, and keep the Chris Ryan of the books at a distance. It's not always successful a supply teacher at Sarah's school who had some connection with my publishers was reeling off a list of their authors, and Sarah was brought up short when she heard my name. After that she came with me to a talk I gave. I'd never really sat down and talked her through what I had done in the Gulf and now she was hearing it in detail for the first time at the age of twelve. While it was odd for her to find out about this world that other people knew all about and she didn't, she says she saw me in a new light and felt really proud. That means the world to me. But for the most part, thank God, I'm boring old dad who dances badly and needs a lot of help with the computer. To be honest, that suits me just fine.