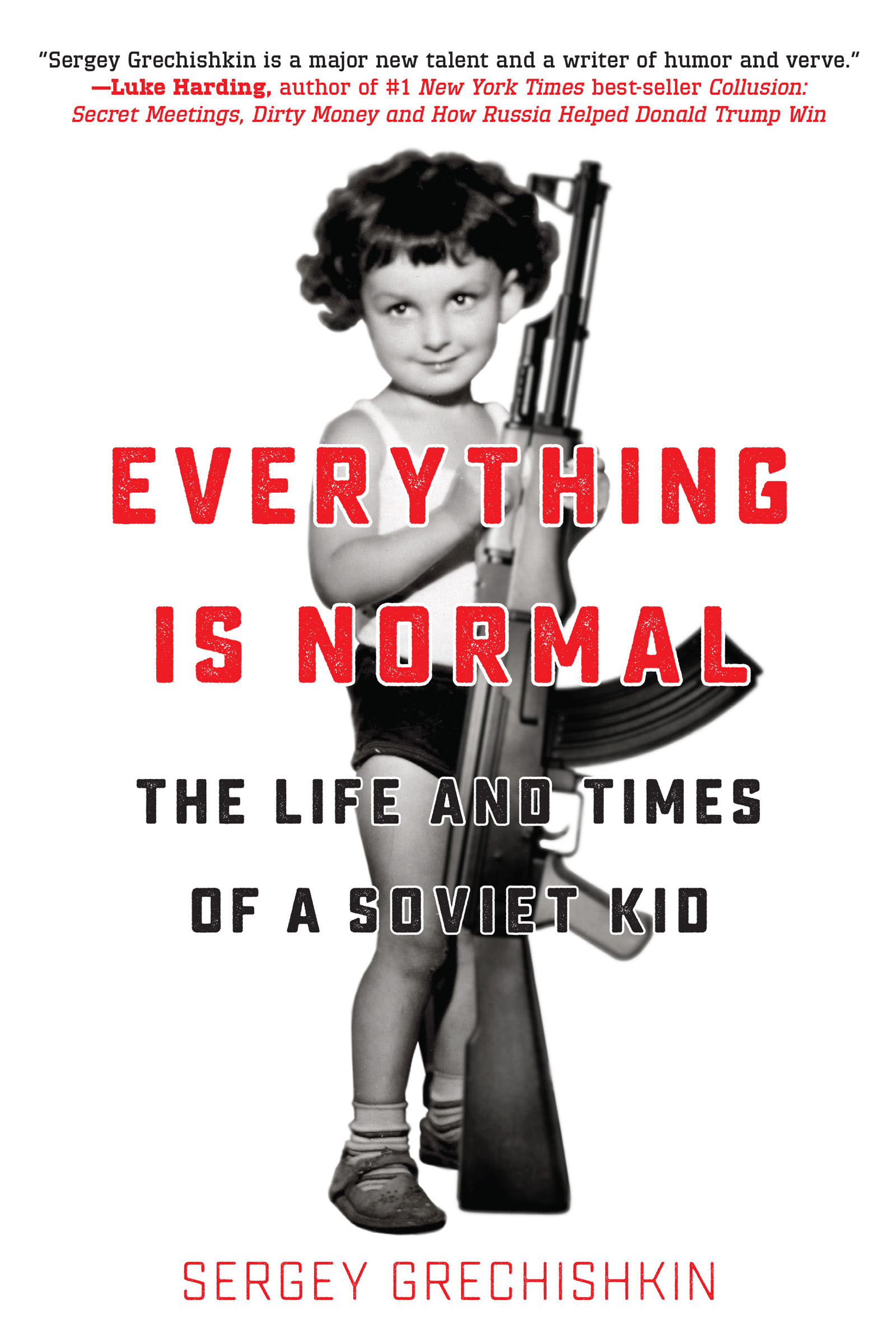

Copyright 2018 Sergey Grechishkin

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Inkshares, Inc., Oakland, California

www.inkshares.com

Edited by Matt Harry

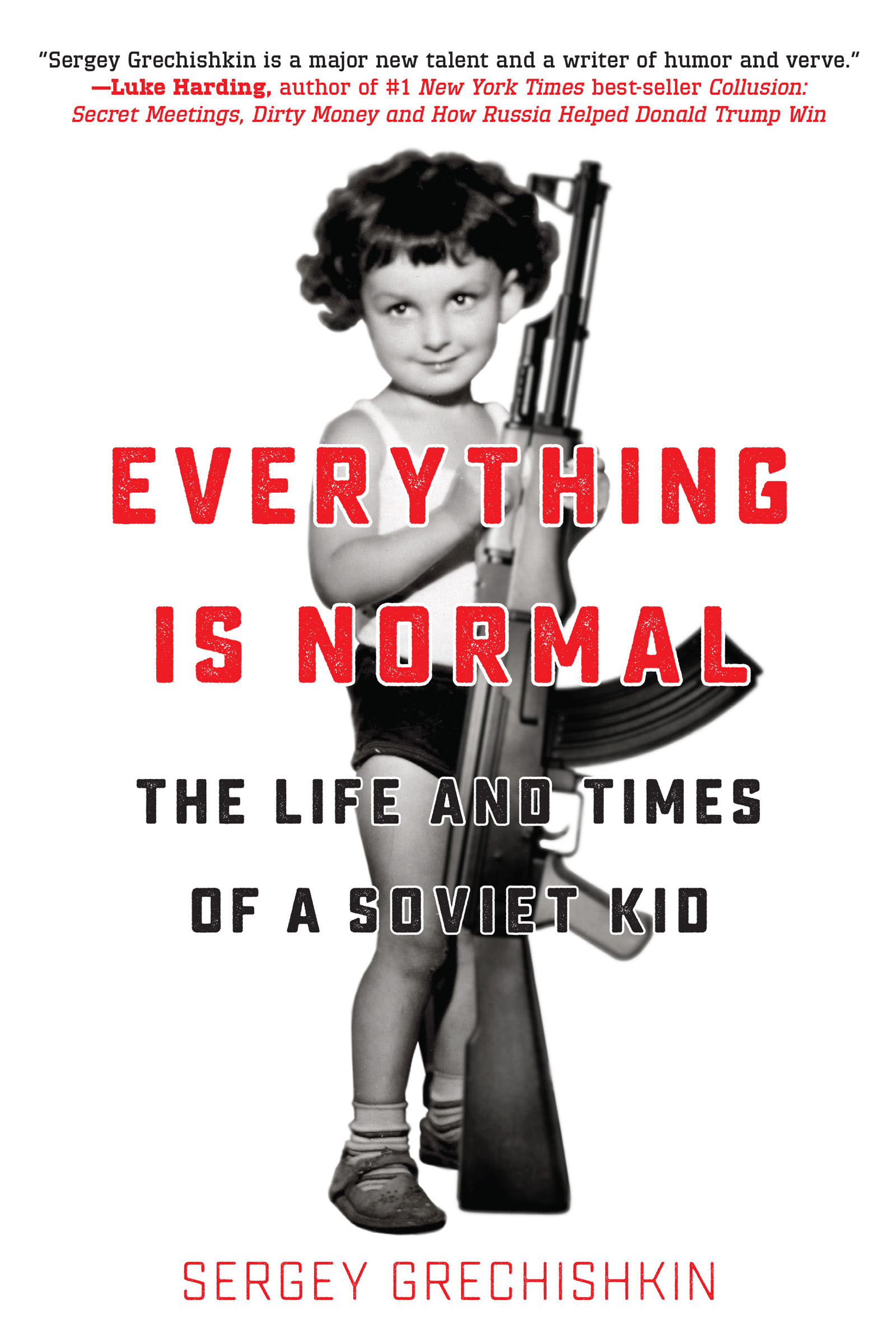

Cover design by CoverKitchen | Interior design by Kevin G. Summers

ISBN: 9781942645900

e-ISBN: 9781942645917

LCCN: 2017955464

First edition

Printed in the United States of America

To my children: Mike, Alex, and Zoya

CONTENTS

NOTE ON IMPERIAL VS. METRIC MEASURES:

1 meter = 3.28 feet = 39.4 inches

1 kilometer = 0.62 miles = 1,093 yards

1 liter = 33.8 fluid ounces

1 kilogram (or kilo) = 2.2 pounds

1 foot = 0.3 meters

1 mile = 1.6 kilometers

1 pint = 0.56 liters

1 pound = 0.45 kilograms

NOTE ON SOVIET PRICE LEVELS IN THE EARLY 80S:

Money in:

40 rubles/month university student scholarship

120200 rubles/month typical salary, whether for a janitor, an engineer, or a ballerina

600 rubles/month salary of a government minister or senior Communist Party official

Money out:

1 kopeck box of matches; glass of soda water without syrup; pencil; slice of bread

2 kopecks local call on a pay phone; newspaper; monthly Komsomol membership dues; glass of tea with sugar; twelve-page school notebook

3 kopecks glass of soda with syrup or glass of kvass; tram ride

5 kopecks subway ride; childrens paperback; pretzel

10 kopecks glass of tomato juice; 1 kilo of salt; 1 kilo of potatoes; one amusement park ride; cinema ticket (child)

12 kopecks bar of childrens soap; 1 kilo of carrots

15 kopecks one game on an arcade machine

20 kopecks 1 liter of gasoline or milk; ballpoint pen; taxi fare for 1 kilometer; ticket to public baths; loaf of rye bread

22 kopecks cream pastry from Sever bakery

27 kopecks bottle of Soviet lemonade

40 kopecks haircut (child); 1 kilo of rice

45 kopecks bottle of Pepsi-Cola

50 kopecks lottery ticket; packet of Bulgarian cigarettes; packet of Soviet chewing gum

90 kopecks 1 kilo of sugar; ten eggs

1 ruble bottle of Troynoy cologne; rental of bed linen on a train

1.10 rubles 1 kilo of bananas

1.50 rubles monthly landline phone charges; packet of Marlboro cigarettes

2 rubles 1 kilo of beef, pork, chicken, or mutton; 1 kilo of zefir candy

2.90 rubles 1 kilo of sausages

3 rubles Kiev cake; 1 kilo of cheese; hardback book; monthly electricity bill; pair of Soviet-made pantyhose

3.60 rubles 1 kilo of butter

4.70 rubles 0.5-liter bottle of vodka (Andropovka)

5 rubles two hours of private tutoring; foreign-made plastic shopping bag with a Marlboro logo (black market); packet of foreign-made cigarettes (black market)

10 rubles foreign-made audio cassette; MoscowLeningrad train ticket; monthly rent for an average apartment

20 rubles 1 kilo of roasted coffee beans

35 rubles plain gold ring; Soviet-made calculator

45 rubles Soviet-made vacuum cleaner; Soviet-made skateboard

96 rubles Soviet-made folding bicycle

100 rubles a Bible (black market)

155 rubles Soviet-made cassette tape recorder

200 rubles foreign-made brand-name jeans, e.g., Lee, Levis (black market)

250 rubles foreign-made brand-name sneakers, e.g., Reebok, Nike, Adidas (black market)

700 rubles Soviet-made color TV

7,200 rubles Soviet-made car (Lada VAZ-2106)

Anekdot

n.: the most popular form of Soviet humor, a short story or dialogue with a punch line, often politically subversive. Being simultaneously independent from and parasitically attached to mass cultural production and authoritative discourse, the anekdot served as a template for an alternative, satirical, reflexive, collective voice-over narration of the Soviet century.

Many of the anekdots under this books chapter headings were once punishable in the USSR by up to ten years of forced labor under article 58 of the criminal code (Anti-Soviet Propaganda). This article was used freely to put critics of the Soviet government behind bars. Today, of course, things are very different in Russia. Now its article 282.

Seth Benedict Graham, A Cultural Analysis of the Russo-Soviet Anekdot (PhD diss., University of Pittsburgh, 2003).

August 19, 2011

I got the call at 7:18 a.m.

My career in finance in London had turned me into a miserable early bird. Vacation or no vacation, 7 a.m. found me sorting through emails.

At the time, I was sitting on the edge of the infinity pool at our Tuscan vacation house. My wife and kids were still asleep upstairs, so I was free to dangle my feet in the water and quietly survey the hills and vineyards surrounding me.

In spite of the view, my heart was uneasy. Back in Saint Petersburg, Russia, my grandmother was ailing. The home attendant who I had hired for her a few years ago had been reporting a steady decline in her health for the past several weeks.

I was working through the avalanche of work emails that had inundated my Blackberry overnight when suddenly the screen flashed the name of Grandmas home attendant.

I knew it right away.

The conversation lasted only a minute or two. As predictable as the news was, it still managed to shake me. On one hand, I had spent my entire childhood in anxious dread of Grandmas death. Some small, subconscious part of me must have still expected her to remain in my life forever. And yet another, more disquieting part of me felt liberated.

After hanging up, I sat there with my legs in the cool water.

Out of nowhere, a memory came back to me, as vivid as though it had happened the other week.

Grandma, a daughter of a tsarist admiral, always knew exactly what to do, and when to do it, and to whom things should be done. Her appearance matched her clout. A tall, somewhat heavyset woman, she never used any makeup and she wore her hair shortas she said, la Deanna Durbin. She had blue eyes and a prominent nose, which held up a pair of large, thick-framed spectacles.

It was freezing cold, but I was snug in my lambskin coat and ushanka fur hat. It was a proper hat, with ear-flaps made of rabbit fur. When I was in kindergarten, the only hat I owned looked like a girls bonnet. I was small for my age and really looked like a girl, so this was even more distressing. To make me feel better, Grandma had taken a metal and enamel army officers badgewheat sheaves framing a red star and the Soviet hammer and sickleand sewed it to the front of the hat. But this new ushanka didnt need any badgesit was a proper big boys hat.

The next day I was turning nine. That made me practically a grown-up. I would have a party, and all my friends would come overat least all the ones Grandma deemed admissible into the house, by virtue of their good breeding and manners. We would eat pastries from the Sever bakery, play with Konstruktor construction blocks, and watch diafilmscolored filmstrips with pictures and captions that we projected onto a wall.

Next page