Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

A HISTORY

OF

LOVE AND HATE

IN

21 STATUES

PETER HUGHES

When the light dove parts the air in free flight and feels the airs resistance, it might come to think that it would do much better still in space devoid of air.

IMMANUEL KANT

Critique of Pure Reason

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Lone and Level Sands

O n 22 May 1538, a large crowd gathered in the sunshine as an extraordinary procession made its way through Smithfield in London. The site had witnessed many executions of heretics and dissidents, including the disembowelling of the Scottish knight, William Wallace and the beheading of Wat Tyler, one of the leaders of the Peasants Revolt. But never before had it seen such a strange double execution as that about to take place.

A month earlier, Thomas Cromwell, chief minister to King Henry VIII, ordered the removal of a large wooden statue from a remote Welsh church. He did so in support of the kings wish to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon and to hasten the break with Rome and the Papacy that this would entail. Relentless in his destruction of Catholic idolatry, Cromwell arranged for the statue of Saint Derfel Gadarn (Derfel the Mighty) to be transported to London.

In Welsh folklore, Derfel was one of seven warriors who survived the fateful Battle of Camlan, at which the legendary King Arthur is said to have died. Perhaps haunted by the experience, Derfel entered the monastic life and died in 660. By 1538, the saints statue at his church at Llandderfel had become a focus for pilgrimages and this was sufficient reason for Cromwell to order its removal.

At the same time as Derfel Gadarns statue was making its way from the Welsh mountains to London, John Forest, a Franciscan friar and confessor to Catherine of Aragon, was sentenced to death for his refusal to acknowledge King Henry as head of the Church in England.

On 22 May, friar and statue had a gruesome meeting.

It began, according to an account by Father Thaddeus, with the statue being carried by eight men, and three executioners holding it tight with ropes, in the manner of a criminal condemned to death. The statue was thrown onto a pile of wood above which the chained figure of John Forest was suspended in a cage.

Hugh Latimer, the bishop of Worcester, gave a sermon urging the condemned man to recant. When he refused, the bonfire was lit. The vast crowd watched as the statue and Friar Forest turned to ash, fulfilling an ancient prophecy that claimed the holy image of Derfel Gadarn would set a forest on fire. The life of a man and the statue that symbolised his identity and values, were consumed in the same fire.

Almost 500 years after the burning of John Forest and Derfel Gadarn, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley and his friend, the banker Horace Smith, wrote competing sonnets based on a passage from the Greek historian Diodorus Siculus. In his Bibliotheca Historica, Diodorus described three statues discovered in the tomb of an Egyptian king, one of which bore an inscription, I am Ozymandias, king of kings; if any would know how great I am, and where I lie, let him surpass any of my works.

Of the two sonnets written about this great ruler, Smiths is forgotten, while Shelleys is one of the most famous poems in the English language:

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.

The vanity of the king of kings, his command to his enemies to despair at the scale of his power, contrast with the lone and level sands that stretch far away. This return of power to the dust from which it rose is the spectre behind every throne and Ramesses II dedicated his life to defying that dust. He erected so many statues and shrines to magnify his glory, that his builders ran out of stone. Undaunted, he ordered them to destroy the temples, monuments and statues of his predecessors and requisition the stone for his own use. It culminated in four enormous 21-metre-high statues of himself at the entrance to the Temple at Abu Simbel in the far south of Egypt. Inevitably, his labours were in vain. By the time an antique traveller came across the remnants of his greatness, all that remained were two vast and trunkless legs of stone.

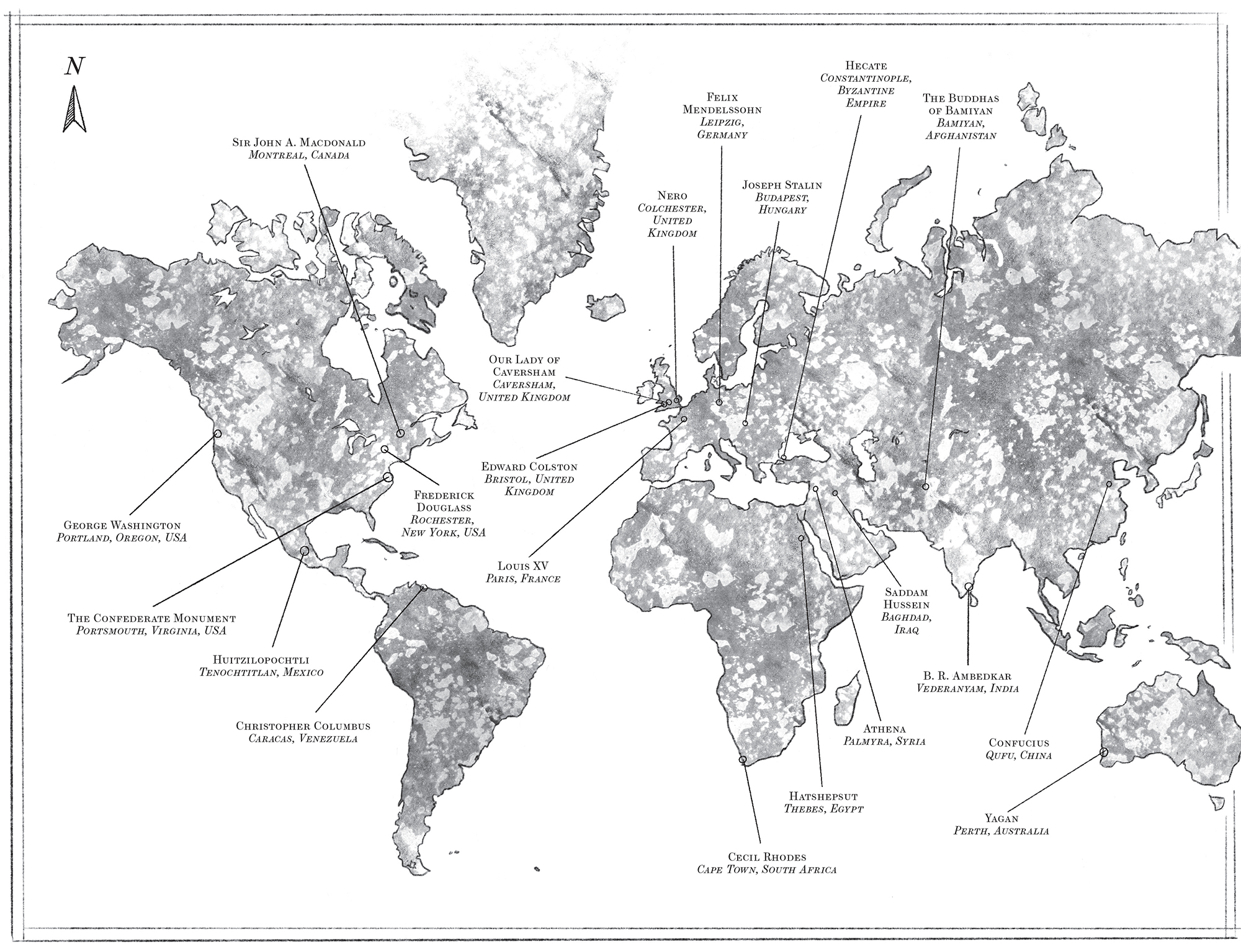

When serving the grandiose fantasies of tyrants like Ramesses II, Joseph Stalin or Saddam Hussein, statues dominate, impress and intimidate. and no society can survive the endless excavation of past injustice. Collapse is inevitable, fuelled by a retreat into identity groups whose self-love and cohesion are predicated on punishing those they accuse of harm and oppression. The destruction of statues is a marker of this collapse.

Yet, for much of our lives, we give little thought to the statues that surround us. As the historian David Olusoga claimed, statues for the most part dont matter. We walk past them every day, theyre grey, and theyre boring. They stand as harmless historical relics. Most of them, he concluded, are benign and theyre benign to me but I can accept that some of them are not benign to other people. However, Olusogas grey and boring statues have a sting in the tail. Whenever social cohesion fractures, they leap out from the background of our lives. Whether we protect or destroy them, they become the stone and steel on which we carve our warring identities.

Today, even as the facts bear witness to the progressive tolerance shown by liberal democracies, mobs gnaw at the imperfect foundations that keep our societies standing. We are like the travellers in Charles Baudelaires poem, The Voyage, who set out to relieve the monotony of their lives only to find, at each destination, an oasis of horror in a desert of ennui. The travellers end their voyage longing to die, to plunge into the depths of the Unknown to find something New. This bleak vision describes the psychological consequences when we cannot accept the failure of reality to bend to our hopes and expectations. Faced with this frustration, narcissists grow impatient with the slow pace of change. They imagine, unlike Baudelaires travellers, they can eliminate the horror and injustice of this life without having to enter the next one. Full of revolutionary fervour, they are blind to the lessons of history. They dream of toppling statues, erasing hierarchies and eliminating injustice. The ruinous outcome is everywhere the same.