Published by Otago University Press

Te Whare T o Te Wnanga o tkou

533 Castle Street

Dunedin, New Zealand

www.otago.ac.nz/press

First published 2020

Copyright Paul Star

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-98-859242-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-99-004825-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-99-004826-5 (Kindle mobi)

ISBN 978-1-99-004827-2 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Editor: Imogen Coxhead

Index: Imogen Coxhead

Author photograph: Adrienne Mulqueen

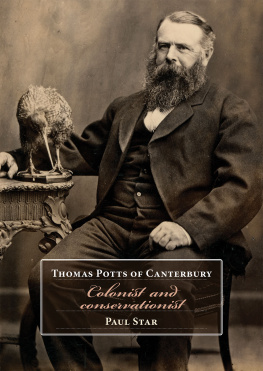

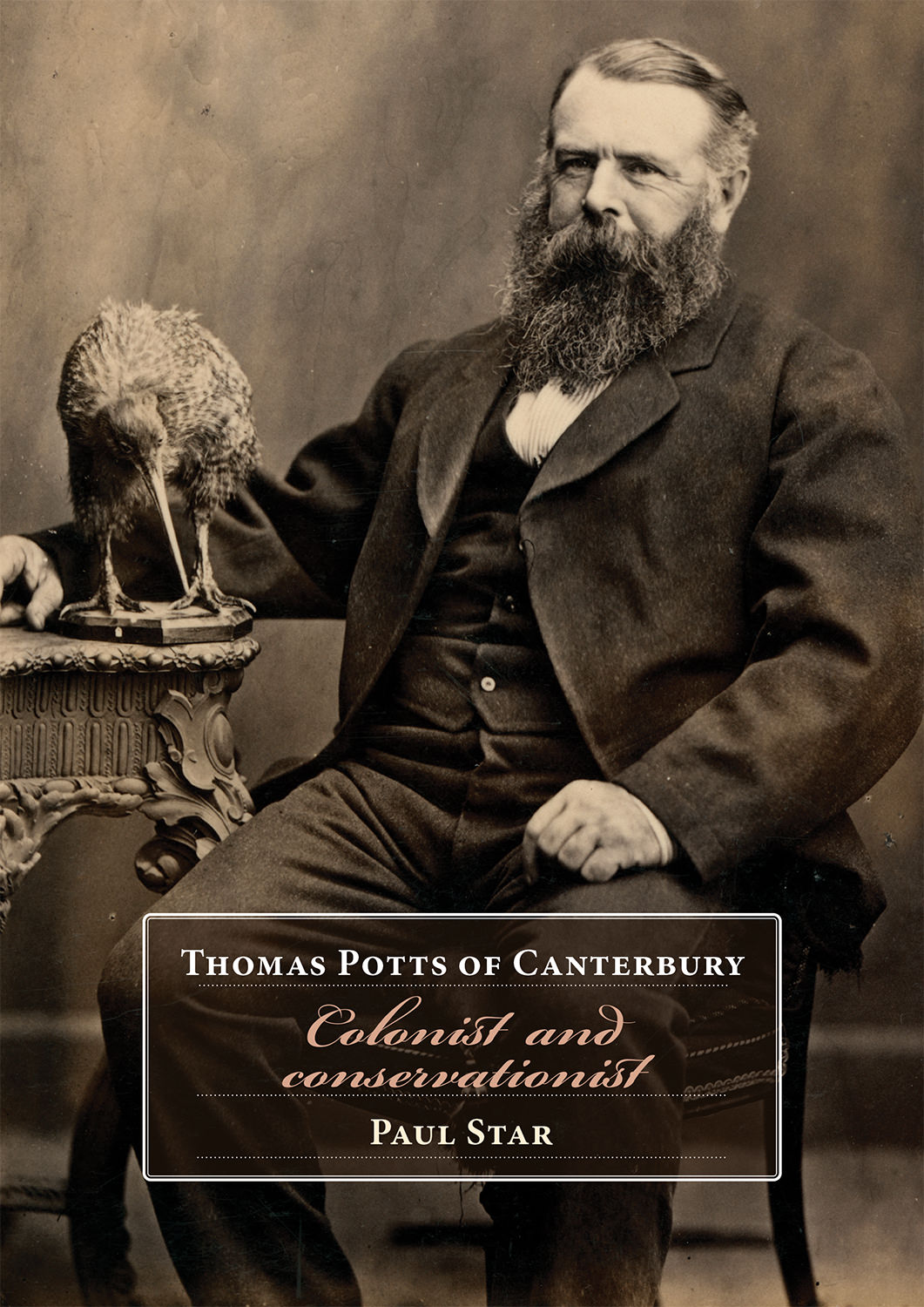

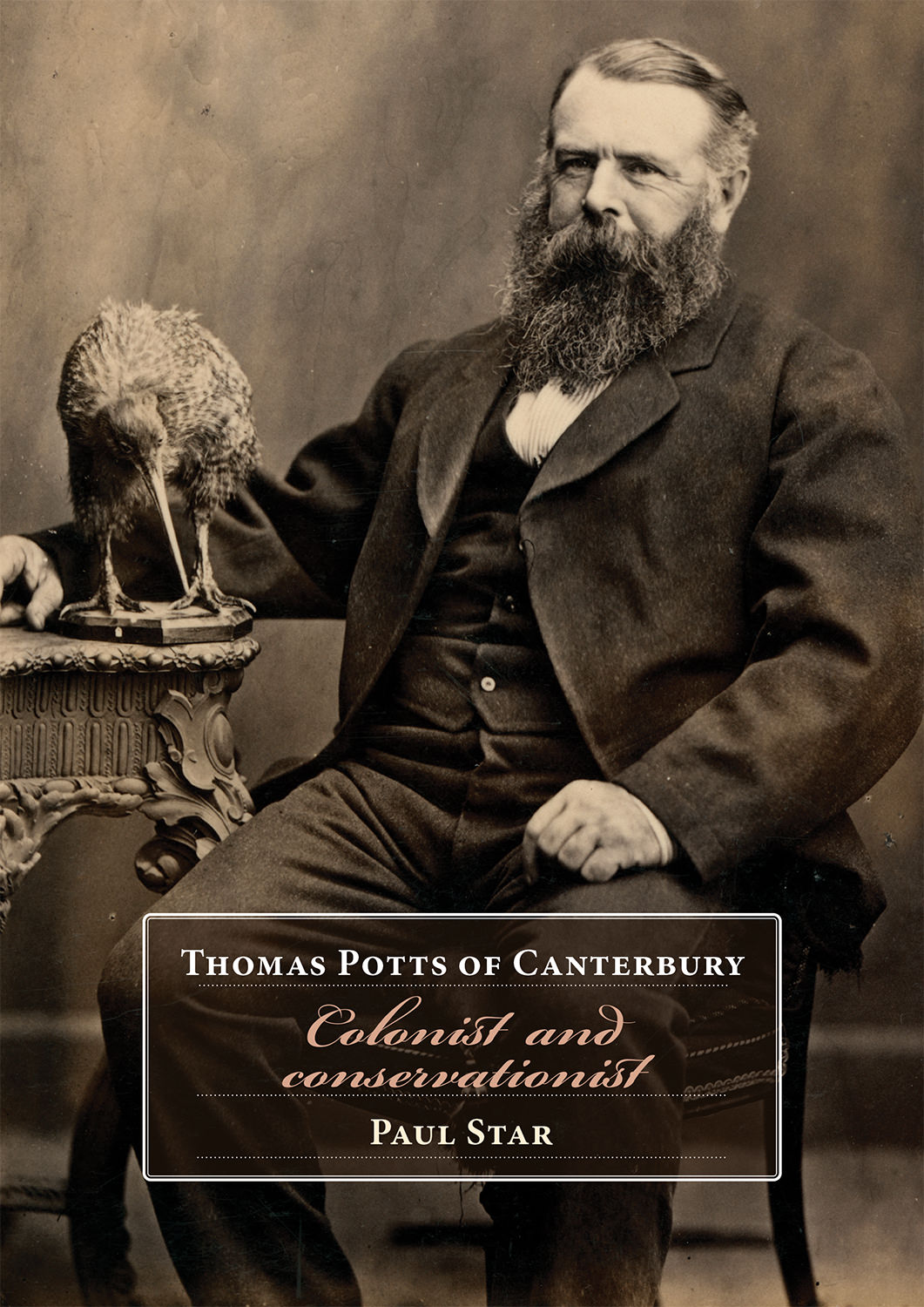

Cover illustrations: A relaxed Thomas Henry Potts in his fifties with a stuffed specimen of the great spotted kiwi, Apteryx haastii. Hocken Collections, Uare Taoka o Hkena, University of Otago: Box-025-002, S19-203a; Celmisia angustifolia, collected in the Ashburton Mountains by T.H. Potts. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: SP046568

Ebook conversion 2021 by meBooks

Contents

I n about 1858 naturalist Thomas Henry Potts (18241888) protested against the destruction of stands of ttara on the Port Hills near Christchurch. A decade later, as a member of Parliament, he made forest conservation a national issue. Through his journalism he raised the idea of protecting native birds on island reserves, and he argued that New Zealand should have national domains or parks. As a pioneering colonist, acclimatist and runholder, however, Potts own actions, as first described in his early diary, threatened the very environments he sought to maintain. His lifes narrative is engaging and his writings have their charm, and both also inform us on the problems we still face in balancing development and conservation. This book is about, and partly by, Potts, and through him about New Zealand and the course and consequences of its European settlement.

Very few colonists anywhere wrote or spoke in sufficient detail for us to chart their personal acclimatisation to a new environment. It is partly the rarity of such detail that justifies examination of the anxieties this involved. Knowing about these few people becomes more relevant as others adopt the attitudes and understandings that they were the first to voice. Over a century after the colonists have passed away, respect and protection for indigenous biota has become an intrinsic component of the national identity of New Zealand and other ex-colonies.

At present Herbert Guthrie-Smith of Ttira, a settler and station owner from the late nineteenth century, is virtually alone among New Zealanders in receiving recognition for his environmental records and ruminations. A generation earlier, however, Potts also noted changes to Aotearoa New Zealands environment, and expressed more trenchant concern about them. Thomas Potts of Canterbury is designed to give the man and his writing the prominence they deserve.

In Part One I describe and interpret Potts life, beginning with his early years in England (182453) as a prelude to the account of his later years in Canterbury, New Zealand, from 1854 until his death in 1888. His fascination with the changes going on around him particularly in animal and plant life, and in landscapes is what makes Potts special. What I have written reflects this, for I refer not only to Potts life, but also to New Zealands natural environment and what he made of it. My account explores the subjects that interested Potts and how he came to be possessed by them. At the same time, I leave room enough to display Thomas Potts the man.

Part Two presents a selection of passages from his diary (185558), kept while living near Rockwood in inland Canterbury, close to present-day Windwhistle and some 80 kilometres west of Christchurch. At the time, this placed him close to the edge of European settlement. The poem by Potts that opens this part of the book was written in his diary in 1856 and provides the title for my selection. Here, Seeking a stranger-land can refer not only to Potts search for an understanding of his new home, but also to our search for an understanding of Potts and his environment. Potts use of the term stranger-land may have stemmed from his reading of Tennysons popular poem, In Memoriam (1850), which includes the line We live within the strangers land, and itself references the biblical text I have been a stranger in a strange land.

I know of only one other occurrence of the term in the nineteenth century in a letter written in 1854 by Isabella Gascoyne, a reluctant emigrant whose family is the subject of the memoir Strangerland by English writer Helena Drysdale. Coincidentally, Gascoyne came to New Zealand on the same voyage as Potts: in a retrospective article about that voyage he referred to her as Mrs. G.:

There was an excellent female barometer amongst the passengers, whose spirits rose and fell in exact sympathy with the weather her custom was to make herself as disagreeable and unamiable as possible to the other lady passengers, that is during fair weather, but let the sea get up, the ship creak and strain and tumble about a bit, Mrs. G. became an angel for kindliness and good nature, only breaking off to pray aloud for mercy on her soul outside her cabin; very often at the cuddy doorway When the sea moderated, her fretful temper made her as intolerable as ever; a civil remark or a smile from her warned her fair neighbours bad weather was coming, and to look out for squalls.

Potts was a superb observer, both of the natural environment and as here of human quirks, and nothing reveals Potts own character more than his own writing.

None of these volumes has been published, but Thomas Potts diary is the one that cries out to be in print. Time and again he breaks free from the straitjacket of listed weather changes, stock movements, gardening and farming activity, visiting and visitors that are the sum total of many such records.

Potts journal is perhaps most valuable for its many references to a natural environment during a time of great change. It also provides a rare and vivid description not only of what pioneering life on an early Canterbury station entailed, but also of what it was like. Almost immediately, he makes himself (pottering about in a purposeless manner) and his wife Emma (risen this morning from the wrong side of the bed) real to the reader as fellow humans.

Part Three, Still Out in the Open, is a selection from among the essays Potts wrote in the final few years of his life (188288), mostly from Governors Bay in Lyttelton Harbour. These essays provide a counterpoint to the content of his journal, written three decades earlier when he was a young man in a very young settlement. By the 1880s he was, in his own eyes, an old man reflecting on the old times of the 1850s and the changes that had taken place to the environment, and to the inhabitants of Canterbury, both Mori and Pkeh.

Next page