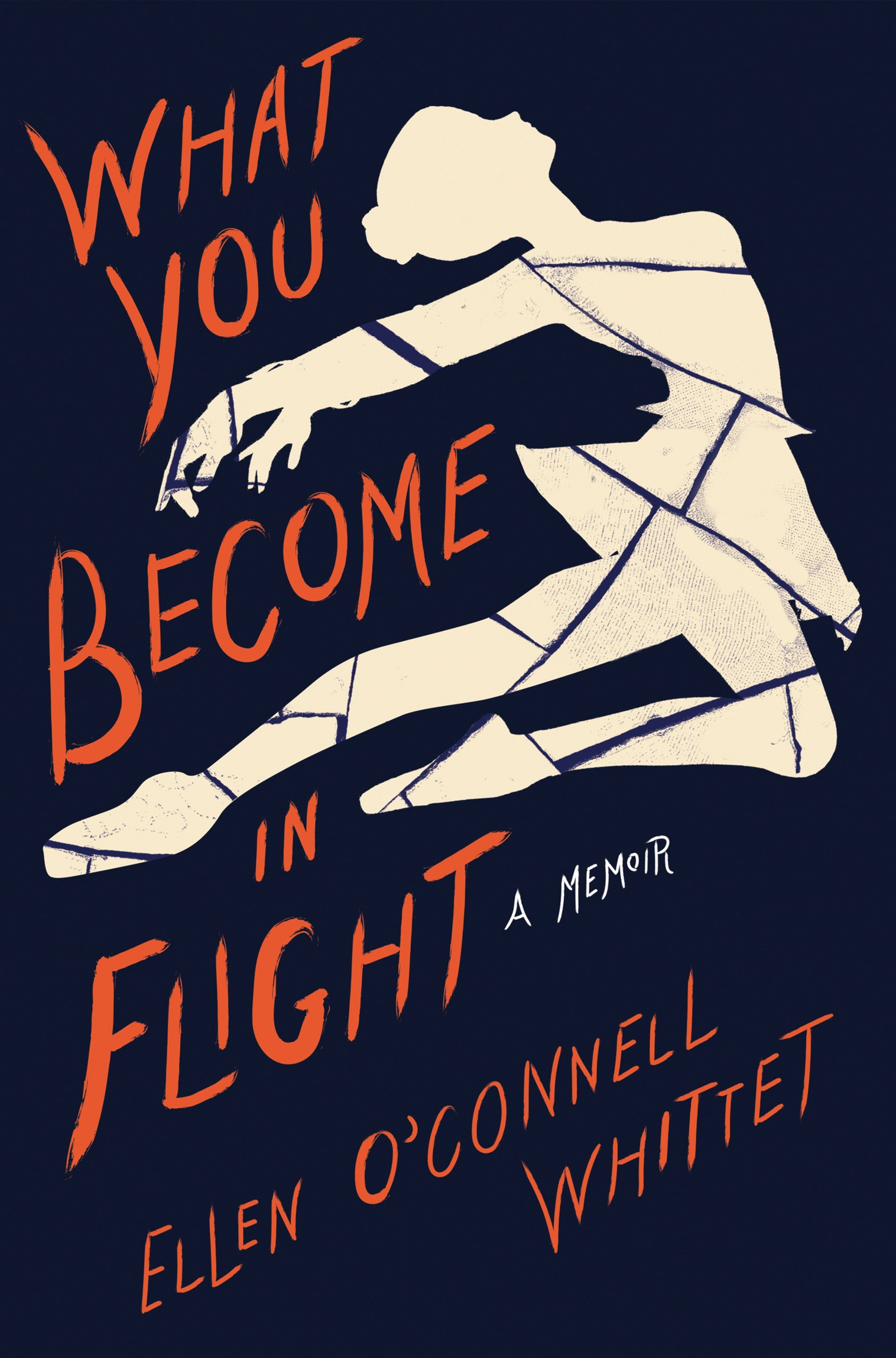

Praise for What You Become in Flight

Revelatory, honest, and wondrous. This is a story of constant becoming. Ellen OConnell Whittet shows us how to confront heartbreaking realities while remaining open. She teaches us the importance of paying homage to our past selves while growing. What You Become in Flight is about the power we harness when we let our losses inform us. I come away in celebration of lifes nonlinear path and the ways we struggle and learn to occupy our bodies.

CHANEL MILLER, author ofKnow My Name

I admire Ellens care in chronicling loss, the body, movement, pain. Her writing is wide awakeprose that holds on as a mechanism for taking flight. Writing that comes up against our fears; that carries out a beautiful working through.

DURGA CHEW-BOSE, author ofToo Much and Not the Mood

Piercing and poetic, Ellen OConnell Whittets memoir explores what happens when we lose a dream we feel like we were destined for. It is much more than a memoir about ballet; it is a memoir about being a woman with a body, about being a person with a hungry heart, someone searching for a place to belong. Whittet writes with astounding vulnerability and grace.

ANNIE HARTNETT, author ofRabbit Cake

An elegant and compelling knstlerroman that begins in the body and ends on the page.

MELISSA FEBOS, author ofWhip Smart

Ellen OConnell Whittets What You Become in Flight is an enthralling, smart, inspiring debut. As a serious ballet dancer, Whittet takes us to the limits of what she inflicts upon her own body, and then investigates the love, violence, fear and obsession that other people inflict upon her, both on and off stage. Here, were taken deep into the world of professional ballet, the grace, the broken bones, all at the hands of an acute observer willing to deftly marry the exquisite and grotesque. But Whittets story is much more than a ballerinas tale. She guides us through phobias, violences many forms, and the tales of other women in her family who form touchstones as her life unfolds into and then out of ballet, through relationships, passions, illnesses, and the biggest questions about what gives us the astonishing grace and strength required for everyday living. This is a beautiful book.

TESSA FONTAINE, author ofThe Electric Woman: A Memoir in Death-Defying Acts

Illuminating and lyrical. Fierce and delicate. Raw and romantic. What You Become in Flight is a true work of art; a contradiction of soft and rough, the grey area between black and white. This is a book not just for dancers, and not only for women. Rather, its a gorgeous lesson to consume, leaving you full of the complex feeling of what it is to be lifted high, dropped hard, and then build yourself back up. Ellen OConnell Whittets words will seep deep into you, fill your head with music, heart with empathy, and, ultimately allow you to understand what it is like to have had wings.

MIRA PTACIN, author ofThe In-Betweens: The Spiritualists, Mediums, and Legends of Camp Etna

What You Become in Flight

First published in 2020 by Melville House

Copyright Ellen OConnell Whittet

All rights reserved

First Melville House Printing: April 2020

Melville House Publishing

46 John Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

Melville House UK

Suite 2000

16/18 Woodford Road

London E7 0HA

mhpbooks.com

@melvillehouse

ISBN9781612198323

Ebook ISBN9781612198330

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019957459

Book design by Betty Lew, adapted for ebook

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v5.4

a

For my mother and father

Ballet is woman.

GEORGE BALANCHINE

Well, its a woman made by a man.

PAM TANOWITZ

Contents

Prologue

It all begins with ballet.

It was nighttime, late winter in California, and I was nineteen years old. That was the winter I decided to stop eating, and began to be noticed.

The ballet we were rehearsing was called Serenade, and I danced it with a tall blond named Peter, who could watch choreography once and memorize exactly what he had to do. It was the kind of ballet I was perfect for, without Martha Graham contractions or Balanchine pirouettes. It was rigid, restrained, correct, viciously classicala piece that could have been danced in France or Russia in the 1850s. It was something that my grandmother could have seen as a young woman, a way of time-traveling through centuries to watch prima ballerina Marie Taglioni dressed as the sylphide in Victor Hugos Paris, clad in white tulle and illuminated by gas lamps.

You run over to me and Ill do the rest, Peter had said to me. Just leave it to me. Off to the side of the mirrored studio, I stood in black stirrup tights and pointe shoes and waited. Peter was the poet and I was the muse, appealing to his melancholic nature as a Romantic-era hero. Although my dance held his attention, I existed for his character arc, not my own.

As the piece began, he crossed the stage in a diagonal, walking, reaching, uncoiling from spinning pirouettes into arabesques, landing from the turn with his leg extended behind him in the air. The light string music suggested the quiet regularity of rain just outside. I could almost hum along to it.

I ran forward and stopped, doing the steps Peter was dancing just behind me a few counts before he did them. Peter was close by but didnt quite touch me unless I leaned so far that he needed to catch me, or I turned so much that his hands would stop my waist, spinning me until I unfolded and caught the music with my body. Though witness to each other, our steps were not the same. Mine were a prologue to his. We were two birds flying next to each other, plunging in a compact series, never wandering apart, or varying our distance from each other, but keeping our place in the sky.

Stage right! The choreographer directed. Downstage! Look at her. Keep your eyes on him as he runs from you. Now run to him.

As a child, I had felt such joy and freedom when I danced, my limbs loose and always in the habit of pulling up and turning out. Dancing let me say something before I was any good at using words. That night in the studio, I tried to remember that, even though these days there was a tug in my hip flexor and a leg warmer wrapped around my tired left ankle.

I followed the choreographers instructions, running on the balls of my pointe shoes. Running in ballet is more like skimming the surface of the stage, the arms still positioned with care, the chest leading. We had been rehearsing this scene all evening, a loop of runs and leaps, and I was feeling tired. Though he didnt look it, Peter, who had been catching me all night, was also likely exhausted. Still, I ran to him, pushing for energy that would allow me to skitter toward a man who was supposed to catch and lift me.