Contents

Pagebreaks of the print version

Guide

To Margarita Castell Martinez, my mother,

and to Mark Solovey,

for helping me navigate the world.

And to the youngest in our family:

Marta, Aitana, Judit, Aitor, Valeria, and Naia.

I hope they will thrive in their own unique

ways and help construct a better world

that values diverse ways of being.

INTRODUCTION

A T TWELVE YEARS OF AGE , a girl named Jessy invents the following system:

Sun with clear sky: four doors

Sun with one cloud: three doors

Sun with two clouds: two doors

Sun with three clouds: one door

Sun with four clouds: zero doors

Jessica Park, Clouds and Doors (1970).

The girl also classifies days into twenty-nine different types, depending on the presence or absence of clouds and the suns position in the sky. She names each day: In summer, dayhigh is a day with high sun and no clouds. In winter, daynothing refers to a clear sky. The state of the sky also has affective consequences: the sun brings her happiness, while any cloud will ruin her mood. When she gets up in the morning, Jessy rushes to look at the sky. Terrifying surprises are always possible. It could be a dayhighdarkcloud day. Despondency, sadness, and despair will follow.

Over the years, Jessy establishes diverse relationships within her system. The different types of days correlate with numbers, flavors, and gum wrappers. The number 3 is rainbow-colored when cloud has color outside looks like rainbow and white inside, her mother tells us. The system also helps Jessy organize and evaluate other experiences in her life. She assigns four doors and no clouds to hard rock music. Why? Because it brings her such intense pleasure that she needs to put four doors in between her and the sound to make it bearable. She allocates two clouds and two doors to classical music. For her evening meal, she measures the green juice she pours into her favorite green cup. The amount shell drink depends on the clouds in the sky that day. The idiosyncratic character of this system reveals the unique mind of its creator, Jessica Park.

Born on July 20, 1958, Jessica Park was delivered by the local doctor, Edmund Larkin, in North Adams, Massachusetts. Her parents, Clara and David Park, took her home to a comfortable house with many books, a piano, and a garden in nearby Williamstown. Her father was a physicist at a prestigious college. Her mother was a homemaker who wanted to teach literature and write poems and essays. Her sisters Katy and Rachel and her brother Paul welcomed their new baby sister. They were eager to play with her and teach her what they knew. But Jessy, as her family called her, did not seem interested in learning from them. She did not seem to need any of them.

Jessys mother, Clara, described her at one and a half years of age:

We start with an imagea tiny, golden child on hands and knees, circling round and round a spot on the floor in mysterious, self-absorbed delight. She does not look up, though she is smiling and laughing; she does not call our attention to the mysterious object of her pleasure. She does not see us at all. She and the spot are all there is, and though she is eighteen months old, an age for touching, tasting, pointing, pushing, exploring, she is doing none of these. She does not walk, or crawl up stairs, or pull herself to her feet to reach for objects. She doesnt want any objects.... One speaks to her, loudly or softly. There is no response. She is deaf, perhaps.

Having watched her daughter intensively over the previous months, Clara noticed certain things she never saw in her other children. Jessy seemed happy, but her mother started to feel uneasy about the solitary nature of her happiness. Clara spent much time playing with Jessy, but also observing her carefully and taking detailed, precise notes about her behavior. One of Claras closest friends was a psychologist. She had suggested Clara record some observations about Jessys behavior. If the Parks needed to bring Jessy to a doctor one day, it would be good to have reliable written information about her. Later she would, in fact, show those notes to many doctors. They would not always appreciate her efforts.

Claras journey to understand Jessys unusual character started in earnest on May 15, 1961, when Jessys pediatrician told her parents that she seemed to be autistic.

In the early 1960s, the Parks took Jessy to a psychoanalytic clinic, hoping for suggestions about how to support her. Instead, the doctors blamed Clara for being the source of Jessys self-isolation. According to the experts in childhood emotional development, Clara was the prototype of a cold, refrigerator mother: an intellectual mother who starved her children of the natural affection they needed to develop properly. These experts saw Claras diligent efforts to study Jessys behaviors in order to figure out why she behaved so differently from her siblings as evidence of Claras intellectual and, therefore, misguided approach to motherhood. Additionally, the experts told her that there was very little they could do to help Jessy.

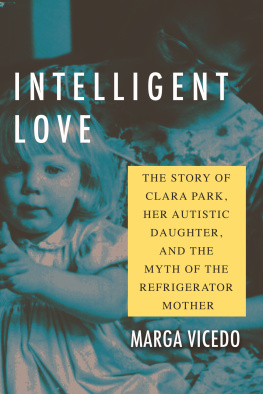

This book tells the story of Clara and Jessy Park, focusing on their struggles to find their place in the world as they fought against narrow visions of motherhood and autism. Clara was called an intellectual mother. Jessy was categorized as autistic. For a long time, both labels made them suffer deeply and restricted what they could become. But in their remarkable journey together, Clara and Jessy broke through the straitjackets of those labels, learning from each other and eventually helping each other to construct a life on their own terms. Exemplifying different ways of combining intelligence and love, Clara and Jessy also helped transform our understanding of what mothers and autistic people can do.

But what was autism? Autism, we read in textbooks, was discovered by Hans Asperger and Leo Kanner in the early 1940s. We will see that the story is more complicated, because what we consider autism to be is the result of various views and practices that were put forth, tried out, argued over, and modified from the 1910s to the present. During that period, ideas about autism changed in striking ways. Autism was first considered a symptom of a mental illness, then a psychopathy, later a developmental condition, and now a disability or form of neurodiversity.

Those changes were driven by a combination of research and changing social perspectives about how we should value peoples different neurological makeups (what is now referred to as neurodiversity). Scientific attention to autism as an independent condition has developed mainly since World War II through research and therapeutic work in several fields: psychiatry, psychoanalysis, psychology, and, more recently, genetics and neurology. The changing views about the nature and causes of autism also entailed new ideas about the treatments and social supports for autistic people. Just as importantly, this period witnessed profound changes in views about disability.

In the 1970s, disability rights activists and scholars in Britain and the United States criticized what they called the medical model of disability. According to its critics, this model privileges the role of medical experts who define disability as an individuals deficit or pathology. Assuming that disability has no value to the person or society, these experts call for a cure or treatment. Critics have powerfully illustrated how the medical model of disability leads to the stigmatization and disempowering of disabled people. Furthermore, the belief that people with disabilities need to be fixed or cannot function as full members of a community encourages what is known as ableism or discrimination in favor of more able-bodied or nondisabled people.