And you shall teach them diligently to your children, and you shall speak of them when you sit at home, and when you walk along the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise up.

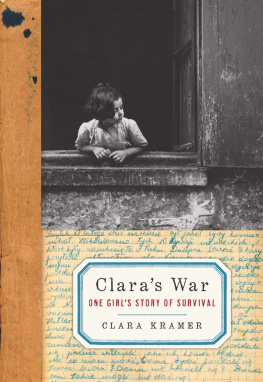

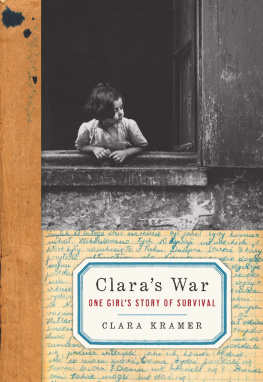

Writing this book was like walking out of my kitchen door in Elizabeth, New Jersey, and straight into my home in Zolkiew. Although the events in this book happened over 60 years ago, they have never left me. As with many survivors, I relive them in the present.

I am 81 years old, and I am one of the lucky ones. Ever since the day I left the bunker, I have done my best to live a worthy life. I have dedicated myself to the teaching of the Holocaust. The privilege of surviving comes with the responsibility of sharing the story of those who did not.

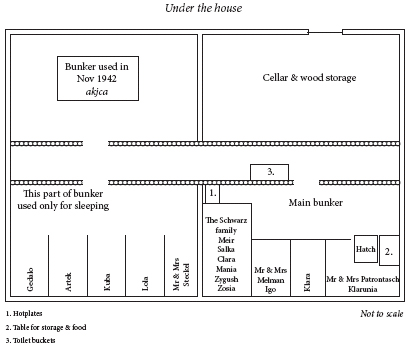

Everything in this book is as I lived and remember it, although I have taken the liberty of reconstructing dialogue to the best of my recollection. I have also used the spelling and names most familiar to me. During the 18 months I spent in the bunker I kept a diary which today is in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC. There was little light and less paper and only one nub of a pencil to write with. I documented as much as I could in my diary, but although I often spoke about my life, the idea of writing it never occurred to me. Thank you to Stephen Glantz for encouraging me and for taking this journey with me back to Zolkiew. And thank you for capturing my life so beautifully on paper. I am so grateful that my great-great-grandchildren will be able to meet those of us who came before.

From my memory to theirs, and to yours.

Where the beginning of a chapter is in italics, it is an extract from my diary.

Clara Kramer

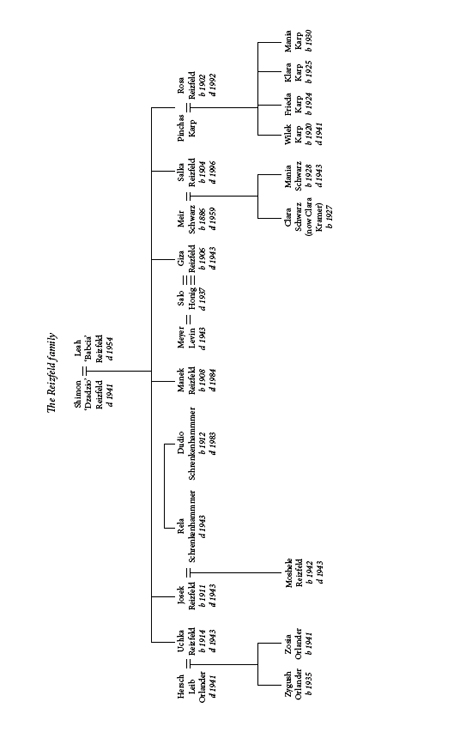

1 September 1939

M y entire family was camped out on blankets and goose-down bedding in the apple orchard behind Aunt Uchkas little house. Out of all my aunts, Uchka was my favourite. Not even ten years older than me and not much taller, she was more like a best friend. Zygush, her three-year-old son, scampered about the orchard picking up fallen green apples. His father Hersch Leib was on his heels, but only managed to catch his shadow. After 20 minutes or more, Uchka finally intervened, handing her little baby Zosia to Babcia, my grandmother, and reaching out to capture the laughing boy as he ran by.

Zygush didnt understand that he shouldnt be laughing or running or having a good time. He would only be quietened with the traditional bribe of a cookie. For him it was just a night-time picnic like those we enjoyed on Paradise Hill. He didnt know that Poland had been invaded by the Nazis that morning while we had been sleeping. Poor Mr and Mrs Gorskis house, on the outskirts of town and surrounded only by ripening rye and wheat fields, had been bombed. There were still planes flying above us headed for Lvov just 35 kilometres away. Even though the noise of the engines was deafening, none of us said a word. In my 12 years of life, I could not think of another time my family had sat together in silence. But we were all petrified that the pilots might hear us and attack us instead. When my restless little sister Mania had run out from under the apple tree to get a better look, Mama hadnt dared raise her voice and had had to resort to feverish gestures to get her to sit back down.

I didnt know who had first come up with the idea that we should all sleep outside, but the idea had travelled faster than gossip up and down our streets. After what had happened to the Gorskis we were afraid to stay in our homes. We had rummaged the closets for our old feather beds, which Mama and Babcia decided could get filthy. After we had packed up some bread, fruit and cheese, the nine of us who all lived together in the same house had walked the kilometre to Uchkas. Our town seemed to have been spilt in two. One half, loaded with blankets and food, was making an exodus, while the other half stood staring, dazed, wondering if they should join us. As we passed near the Gorskis, I was filled with a morbid curiosity. I had never seen a bombed-out house before and wanted to go and look at it, but Mama wouldnt hear of it. She didnt want us separated. In typical fashion Mania had ignored her and already run ahead to Uchkas, while I was stuck walking at a snails pace. Babcia and Dzadzio, my grandparents, who were portly and only walked distances in considerable pain, kept telling us not to worry about them and go on already. But Mama didnt want her parents to be alone if there was another bombing.

Mama was nicknamed Salka the Cossack because she went through life as if she were mounted on a horse, wielding a sword at any of lifes problems. She could manage anything from her kitchen table. But no matter how much we talked and talked and talked, trying to make sense of the new reality, today was a day of questions without answers.

Across the fields and in all the pastures and farms surrounding our small city of Zolkiew, dozens of other families were getting ready to sleep under the stars. Even though it was a warm September night, with the air fragrant with the scent of newly mown hay, no one could sleep. But eventually exhaustion had triumphed over fear and, in ones and twos, everyone but me had succumbed. I had never been a nervous and anxious girl; I was the quiet, studious daughter. But as I watched and listened for more planes to come, I felt I would never be able to sleep again.

In the distance I could make out the silhouettes of Zolkiews baroque church spires with their pregnant onion tops and golden domes. Not a light was on, and my familiar town looked eerily deserted, almost haunted. It felt as if the wars shadow had physically darkened our town. Our family had been here in this corner of Galicia in south-eastern Poland for ever. I couldnt imagine living anywhere else. We had been rooted here longer than most of the white birch and the Russian pines that formed the islands of forest in the steppe. I had never heard Dzadzio and Babcia speak of another place in our familys history.

As long as I could remember, my family moved and lived in a pack. You couldnt turn around in our little stone house without bumping into somebody. Now, spread out under the apple trees, sleeping in piles, huddled together on the feather beds, using each other as pillows, we resembled a pack more than ever. The only one missing was Aunt Rosa, who lived in the thick forests of central Poland. When Aunt Rosa had got engaged to her husband Pinchas, Babcia had gone into mourning. Rosa was the prettiest of the sisters and Babcia had always said she could have had any man she wanted in town. It wasnt that Pinchas, a timber merchant, wasnt a catch any mother wouldnt brag about, it was because he lived on the other side of Poland in Josefow and she would have to leave Zolkiew.