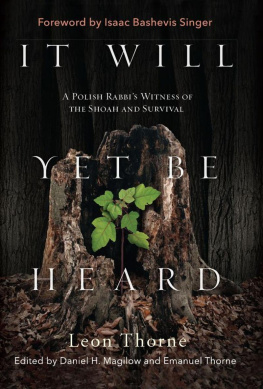

It Will Yet Be Heard

It Will Yet Be Heard

A Polish Rabbis Witness of the Shoah and Survival

Leon Thorne

Edited by Daniel H. Magilow and Emanuel Thorne

Foreword by Isaac Bashevis Singer

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW BRUNSWICK, CAMDEN, AND NEWARK, NEW JERSEY, AND LONDON

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thorne, Leon, 19071978, author. | Magilow, Daniel H., 1973, editor.

Title: It will yet be heard : a Polish rabbis witness of the Shoah and survival / Leon Thorne ; edited by Daniel H. Magilow.

Other titles: Out of the ashes

Description: New Brunswick, New Jersey ; London : Rutgers University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003441 (print) | LCCN 2018022576 (ebook) | ISBN 9781978801660 (epub) | ISBN 9781978801684 (web pdf) | ISBN 9781978801653 (hardback)

Subjects: LCSH: Thorne, Leon, 19071978. | World War, 19391945Personal narratives, Jewish. | BISAC: HISTORY / Holocaust. | BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Religious. | RELIGION / Judaism / History. | POLITICAL SCIENCE / Political Freedom & Security / Human Rights. | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Jewish Studies.

Classification: LCC D811.5 (ebook) | LCC D811.5 .T48 2018 (print) | DDC 940.53/18092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003441

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2019 by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

This book is dedicated, in deep humility, to those heroic martyrs who perished in the European ghettos and concentration camps because they were Jews and because they lived Jewish lives. They died as the world looked passively on. May this book serve to remind mankind of what happened to themand may they know, in heaven, that they are remembered, their stories told, their experiences recalled, and their heroism extolled.

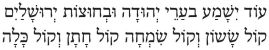

It will yet be heard in the cities of Judah, and in the streets of Jerusalem.

The voice of joy and the voice of gladness, the voice of the bridegroom and the voice of the bride.

Jeremiah 33:1011

Contents

In the 1961 preface to the first edition of his memoir, Rabbi Leon Thorne (19071978) justified publishing this remarkable autobiographical account of his life during the Holocaust and its immediate aftermath with a curiously defensive tone. Thorne noted that by the early 1960s, there were already thousands of magazine articles and hundreds of books and plays and poems and true-life accounts of Jews wartime experiences. Nevertheless, he added, No life is like another and no man has lived another mans life. I feel that what happened to me was different in spirit if not in detail from what others lived through.

Both before and after the Holocaust, Thornes life was one steeped in Jewish learning and tradition. Born in 1907 in the oil boomtown of Schodnica in Eastern Galicia, then part of the Hapsburg Empire, he studied philosophy and theology at universities in Lemberg (Lww), Vienna, Wrzburg, and Breslau. He was ordained when only nineteen, and between 1945 and 1948, he served as a rabbi to surviving Jewish communities in Rzeszw, Poland, and Frankfurt am Main, Germany, before immigrating to the United States in 1948. Thornes wartime memoir indeed stands aparteven among the scores of accounts that have appeared since 1961. His Holocaust experiences were not those of a secular Jew who suffered in the larger and better-documented ghettos and camps like Warsaw, d, Auschwitz, and Dachau. Leon Thorne was a religious man who instead confronted death in places with relatively unfamiliar names like Schodnica, Sambor, Drohobycz, Lemberg, and Janowska. Memoirs of this sort are comparatively rare among firsthand accounts of the Holocaust.

The New Yorkbased Yiddish newspaper Der Tog first serialized Thornes story. It was originally written in German and later translatedsometimes awkwardlyinto a heavily edited English version that appeared under the title Out of the Ashes in 1961. Further editions appeared in 1976, yet the memoir never found a wide readershipnot only because the Holocaust had yet to become the household word it is today but also because the book appeared quietly through Rosebern Press, a small publisher in New York. Thorne himself felt that the translation did not entirely represent his experiences accurately, so in the mid-1970s, he began to revise and expand a text that he had first written in German while hiding in a bunker, perhaps fearing that no readers of Yiddish would survive the war. To this first part, which conveys the desperation and immediacy of a memoir composed in the middle of a genocide, Thorne later added a second part with additional stories of the Holocaust and its immediate aftermath. This subsequent historical treatment, written decades after the fact, is a memoir as well but also a witness account and a work of history by a trained scholar.

Unfortunately, Leon Thorne died in 1978 before he could publish the expanded text, thereby depriving posterity of a rich and deeply moving account of the Holocaust and its aftermath. His view of his experiences as unoriginal might technically be true but only because the single-minded determination of Germans and their auxiliaries to murder every Jew has standardized the sorts of horrors that readers encounter in Holocaust memoirs. Many of the episodes Thorne recounts resonate closely with classic texts by Anne Frank, Elie Wiesel, Primo Levi, Art Spiegelman, and others that have found broad audiences. But Thornes work provides insights into the Holocaust that few other books can. We see the events through the perspective of a religious man who not only served as a Jewish chaplain in the Polish Army but also witnessed antisemitic violence during and after the Holocaust and who helped smuggle Jews out of the ruins of postwar Europe. Beyond these unique experiences, his work adds nuance to commonplace understandings of moral behavior in the Holocaust not only of perpetrators but also of victims.

Part I begins and ends in a claustrophobic hidden bunker underneath a Polish peasants stable. It depicts familiar scenes and characters of the survivor memoir genre, as it documents Thornes time in the ghettos of Sambor and Drohobycz and in the Janowska (or Janover) forced labor camp in Lemberg (Lww). In part I, we read troubling reports of sadistic and capricious camp guards, heart-wrenching accounts of the murders of entire families, and passages that emphasize that those who did not experience the Holocaust personally can never truly grasp it. Part II begins in the immediate hours after liberation when Thorne and his companions emerge like the living dead from their underground hideout. Their initial joy of liberation soon collides with the reality of the mass destruction that surrounds them. In words that capture the conflicting emotions of survival, Thorne writes, We envied our dead loved ones who no longer had to cope with a world left cold and barren by war. I recalled the words uttered by the prophet Ezekiel when he found himself in the midst of the valley of dry bones: And He said to me: Son of Man, can these bones live? And I answered: O Lord, Thou knowest.