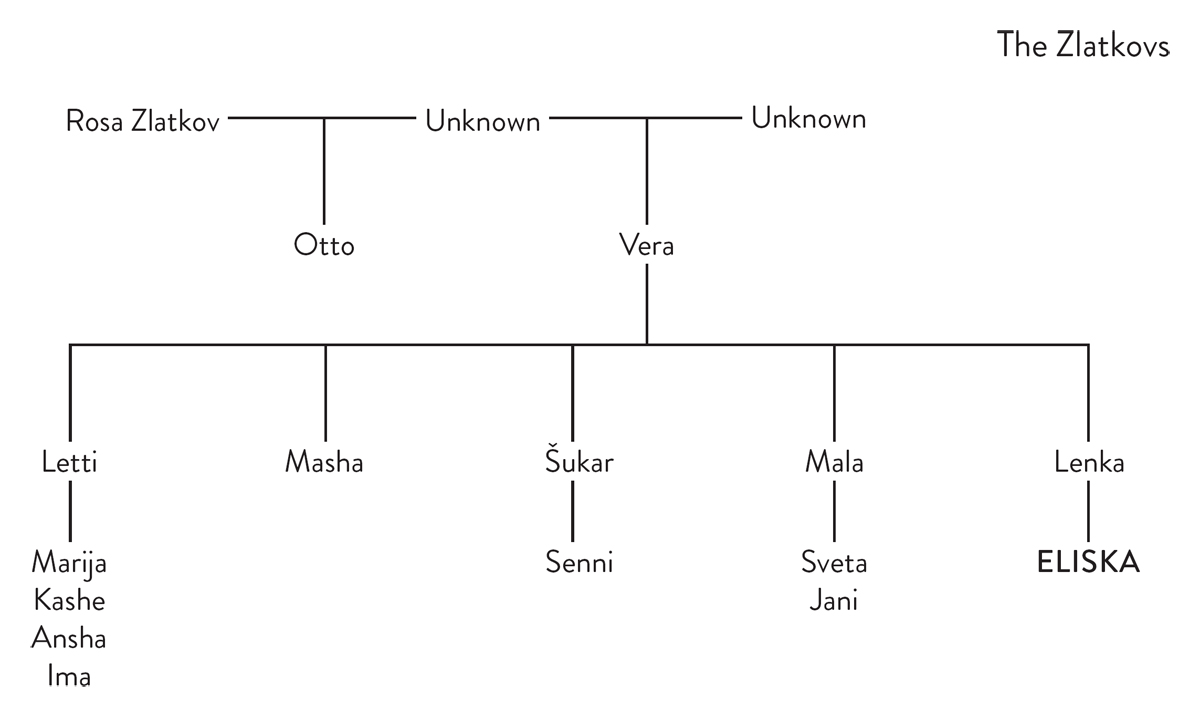

My mothers side of the family are Romani. Gypsies. No baby-snatching and tambourines, just resilient souls and richly coloured skin. I look most like them, with my brown eyes and scars. I dont have the richly coloured skin, though. Instead of deep bronze or golden ochre, I came out the colour of sunflower oil and, thanks to childhood malnutrition followed by years of low iron levels, Im now the shade of an off-brand Simpson.

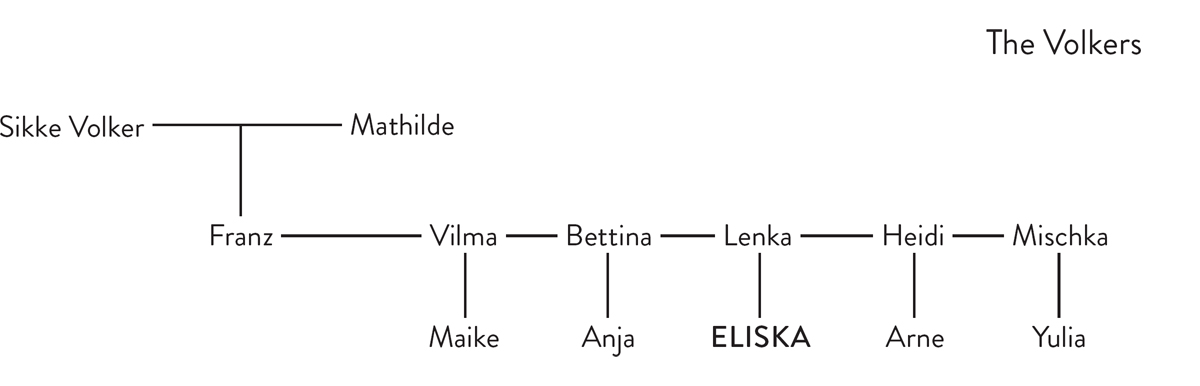

I was born in the nineties to a 13-year-old girl called Lenka Zlatkov. If this were a TV series, wed grow up like sisters, understanding each other on a deep level and bonding over common interests. Ma would sit, engrossed in me, hugging a cup of tea while I painted my nails and moaned about my friends. Maybe wed even go clubbing together.

In reality, having a mother barely a decade older than you isnt fun. Ma was at best a frenemy and at worst the reason I slept with a penknife under my makeshift pillow.

Outwardly, Lenka Zlatkov was beautiful. Typically defiant, instead of looking haggard and rundown in the bleakest of living conditions, she flourished. All of five foot four, but with a mouth that would give a town crier a migraine, she was a fiery Gypsy woman with attitude. Her thick, glossy hair was as rebellious as she was, preferring to fall down the sides of her face instead of staying in the plaits shed weave. The coral-coloured lipstick brightening her full lips and stolen kohl pencils lining her creamy brown eyes, combined with her wild wavy hair, made Ma look radiant. I loved watching her relaxing; shed sit with her eyes closed, swinging her foot out of the window mindlessly as the scraps of sun that reached us bounced happily off the three gold hoops hanging from her long, wide nose. During these moments, Id ache to be just like her, to be as effortlessly beautiful as that. Even the stretchmarks branched over her stomach, legs, shoulders and arms were fascinating to me; she was so unashamed of them that I was almost proud when, years later, I discovered the same faded vine-like marks on my own body. As if we were both part of the same tree that marked us with its long, winding arms.

As lovely as she was to look at, she was the polar opposite to be around. All the gentleness suggested by her soft coral smile vanished as soon as she spat out her trademark snide comments, and the scathing insults for which she was famed. When she was about to savage someone verbally, Lenka had a signature look: shed raise her left eyebrow over slightly narrowed eyes and bite the inside of her bottom lip, whilst smirking enough to flash a glimpse of her gold tooth. She reminded me of a coiled viper waiting to strike. That look meant Ma was about to make someone cry.

I was never spared her tongue lashings in fact, she worked out some of her best material on me. How I reacted to an insult determined how often shed use it on other people. She once said I had a toad-face and I wailed for hours, only to find my cousin Sveta wailing at our Auntie Lettis feet the next day, because Lenka had called her toad-faced too. Sensitive soul that I was, I began weeping next to her because I felt guilty.

Lenkas hysterics and talent for verbal abuse were inherited from her mother. Id grown up seeing my Grandma and Ma inches away from each other screaming wildly, then, minutes later, lazily chatting away.

All my aunties were treated harshly, but for Ma it was worse. While her sisters joined the family business in their mid-to-late teens, Ma was put to work at the age of 11 because she kept irritating my Grandma with the amount of food she ate.

It was Mas career that was her great love. Lenka Zlatkov was, and tragically still is, an international saleswoman. India, Hungary, Romania, a dodgy month in Ukraine, and back home Ma has worked in some exotic locations. Selling herself.

She is a prostitute. Not the perfectly coiffed, too-many-teeth-in-her-face, Julia-Roberts-in-Pretty-Woman type, but the penknife-in-her-bra-lining, abortion-scars and knuckle-duster-hidden-in-her-plaits type. Shes more likely to knock a man out and rob him blind than fall in love with him, and all with that signature smirk on her beautiful face. Its probably how she managed to afford a set of knuckle-dusters in the first place.

At 11, Ma started to travel with my Grandma all over our city and the neighbouring ones to sell herself. She was a favourite with all the white men trawling the streets looking for some #Gypsylove.

Shed recall with glee how many men wanted her and how they couldnt even wait long enough to find a room: theyd have her behind buildings, in cars, or down rubbish-cluttered alleys. In Mas mind, it was the ultimate compliment that these men dressed in their clean clothes would risk the filth just to have her.

Any normal 11-year-old would be distraught, but not Ma. The few times shed told me about the start of her illustrious career, shed speak with a kind of arrogance. It validated her, having men pay for her. It was the reason she bounced around with that theatrical walk of hers a cross between a shampoo advert and a salsa performance, all hair flips and hip-swaying.

It wouldnt be fair to say it was her work that made our relationship so volatile; my cousins and their mothers had wonderful relationships, despite the work. It was my permanently self-absorbed, escapist haze and Mas resentment of me that made for such a sour mix.

As I grew older, the verbal warfare got worse and worse. Ma would say the nastiest things to me. I always kind of knew she wasnt fully serious; it was just her manner to express herself by flinging savage threats and crushing insults, her arms thrashing as violently as her words. The usual dramatics of a Gypsy mother.

One day I will cut your tongue out of your mouth!

I wish I had ripped you from my womb when you first started feeding off me. Leech!

All you have to offer is a tight hole!

Eventually, the shock of her banshee episodes wore off, and I stopped caring. Living where we did made us bulletproof to verbal insults in any case. We were subjected to the worst racial abuse on a daily basis and after a while, instead of gasping and recoiling at the savagery of the insults, we just rolled our eyes and sighed at the lack of originality.

This was our relationship: shed say some foul shit, Id either cry or be sarcastic back and it would all be forgotten within a few hours.

The physical fighting took longer than a few hours to get over, however.

From the way shed get up in the morning and dance outside whilst oiling her hair, to the way shed batter me with her shoe for doing the same, Ma was an enigma. There were times, I have to admit, when Ma was completely justified in battering me. I was dopey, but I wasnt a timid child, and I wasnt a well-behaved child. I spent half my time daydreaming or making up stories, and the other half being dragged by my cousins to go stealing and fighting.

Id only ever steal food. I wish I could give you some Oxfam-leaflet line about only stealing enough to fill our starving, malnourished bodies but truthfully, instead of bread and water to survive, we stole doughy Roky rolls and ice-cold bottles of Kofola cola.

Id fight because Id inherited my dads fists and Mas tongue not the best combination. I took great pleasure in chasing the little white kids who were brave enough to peer around the corner to our neighbourhood and scream Rats! The Nazis are coming! A good Gypsy is a dead Gypsy! The look on their faces as a gaggle of dirty, brown Gypsy kids rounded the corner with makeshift catapults and pockets full of rocks ready to launch at their milky white legs still makes me cackle to this day.