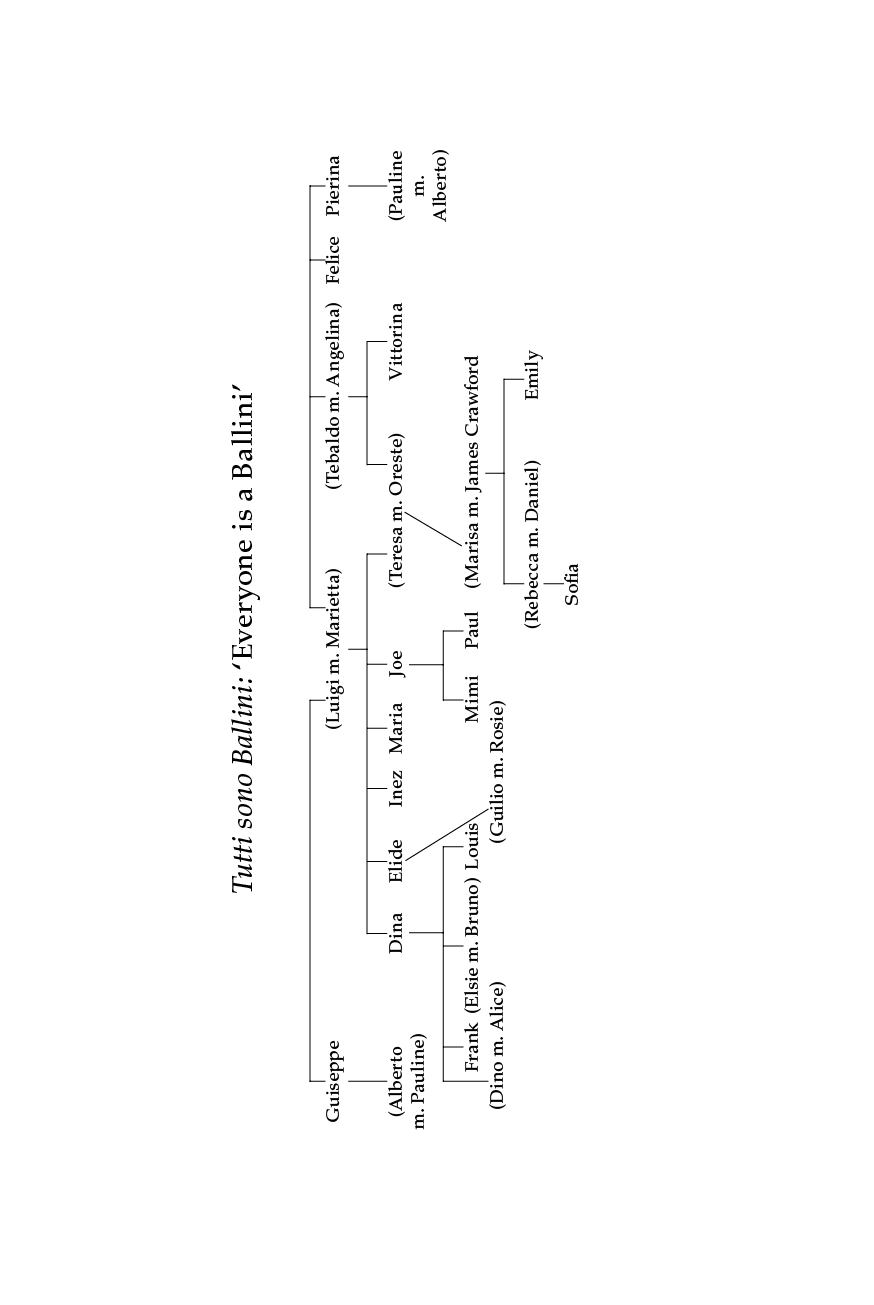

Dr Rebecca Huntley is a researcher and author with a background in publishing, academia and politics. She holds degrees in law and film studies and a PhD in gender studies. Rebecca is the executive director of The Ipsos Mackay Report and the author of two books, The World According to Y: Inside the new adult generation and Eating Between the Lines: Food and equality in Australia .

Rebecca is a regular contributor to essay collections, magazines, newspapers and online publications and is a feature writer for Vogue Australia . She is also a sought-after commentator on social trends on radio, in print and on television, is married with a young daughter and lives in Sydney.

Contents

To my nonna , my mother, my sister, my daughter...

Australia

Australia

young smiling land

circled by the oceans

are you listening to me?

I have broken my heart

to understand you, to know

the blood in your veins,

to draw new things

from the gardens of your poetry.

You know, this voluntary exile

now is a sweet fusion

between past and present

between reality and a dream

between grass and dirt.

With the passing of time

something in me has been extinguished

and then it has risen to enlighten me

in the dusk of the evening.

Integration

is discovered little by little

like the words

of a great love

Australia of my heart

Mariano Coreno

When this war is finished, if the story [of internment] is ever published, it will astound decent honest Australian people.

The Hon. Cecil Nugget Jesson

Labor Party Queensland parliamentary representative for Kennedy (193550) and Hinchinbrook (195060)

Prologue

February 2011

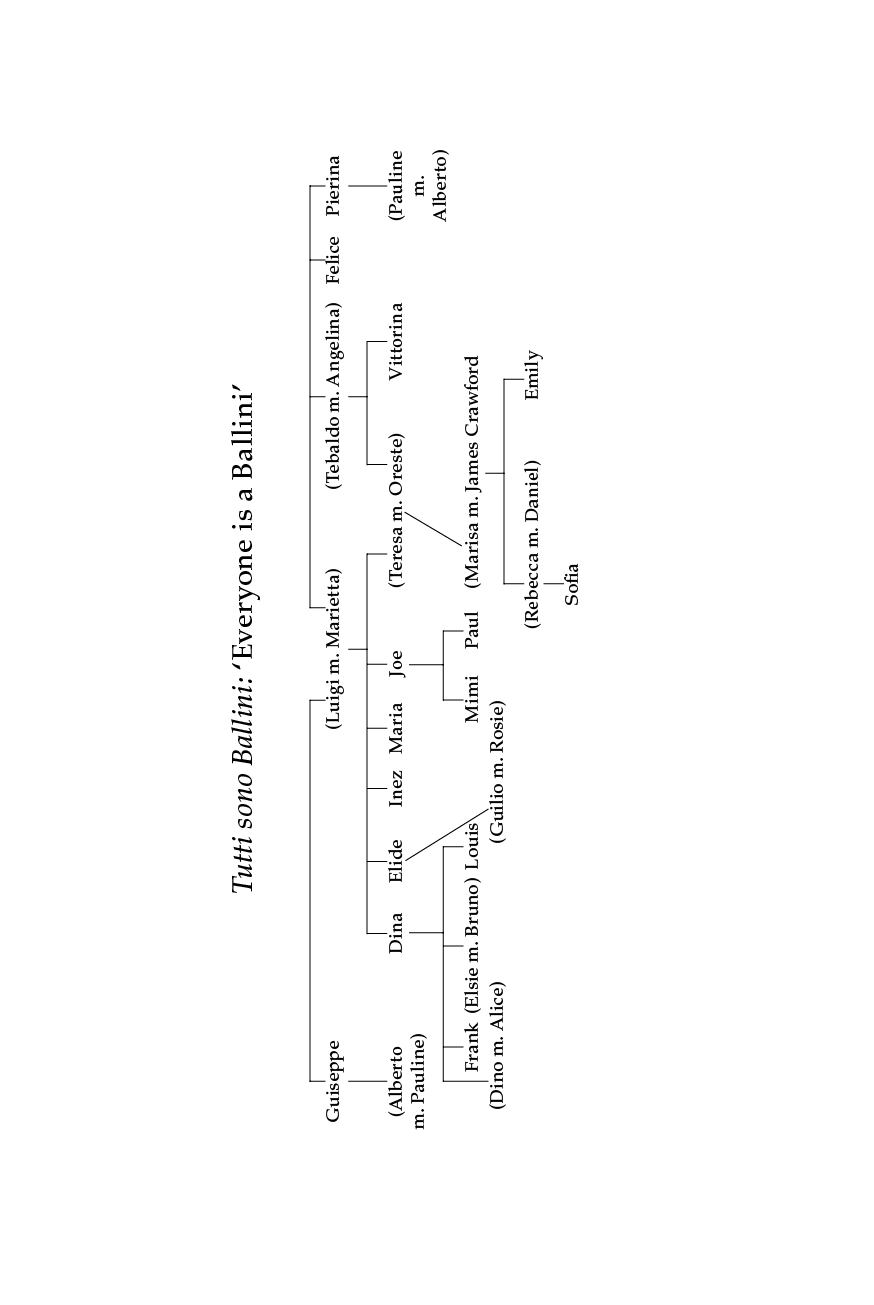

I am sitting at my kitchen table with my mother on a humid summers day. I am talking to Mum about the past asking her questions about her childhood, everything she remembers about her relationship with her mother and grandmother. But she is not listening to me. Her attention is on my three-year-old daughter Sofia, who is busy twirling around on the polished wooden floorboards in new cotton socks. Sofia stops her ballerina dance abruptly and disappears into her room, emerging half a minute later with some soft toys that she piles onto her grandmothers lap.

Grazie carina! Bella bambina! my mother says in a high-pitched, affectionate voice. Voi un biscotto? Si? Ecco-la! Mum takes a sweet biscuit from the plate on the table and gives it to Sofia, who immediately shoves it into her cherubic mouth.

Di grazie Nonna, grazie Nonna.

Grazie Nonna , Sofia says in singsong Italian, spitting crumbs on the floor. I watch this interaction and try to stifle a small surge of resentment. In just a few seconds Mum has spoken more Italian with Sofia than she has with me in forty years. I think back to the time when I was taking lessons to improve my Italian language skills, how my mother rebuffed all my requests to get her to talk to me in her first language. Yet she speaks happily without prompting to my daughter.

The little surge subsides when I realise that talking to Sofia must be easier than talking to me. The love between grandparent and grandchild is a joyful thing, clean and uncomplicated. Mum can speak Italian to Sofia and it can be fun, a game between them. She can be a nonna and all nonnas speak Italian to their grandchildren. There is no sadness or regret, just love and biscotti.

My mothers mother my nonna spoke Italian to us from time to time when we were children. I recall she was a different person when she spoke Italian more confident, opinionated, and vivacious than when she spoke English. I wonder whether, if I had been able to really talk with her in her first language, I might have got to know her better. I wonder whether I could have asked more questions about her life and understood the answers.

Growing up, I always saw Nonna as a relatively uncomplicated person, content in her role as housewife, with no greater aspirations than to support her husband, raise a happy daughter and help that daughter raise even happier daughters. When my nonna died I found out she was a different person than I assumed, with a history full of moments of heartache and bravery. In my attempts to find out about her life, I found out more than I could have anticipated about love, loss, identity, family and the unbelievable things people do in times of war.

The Train North

August 2000

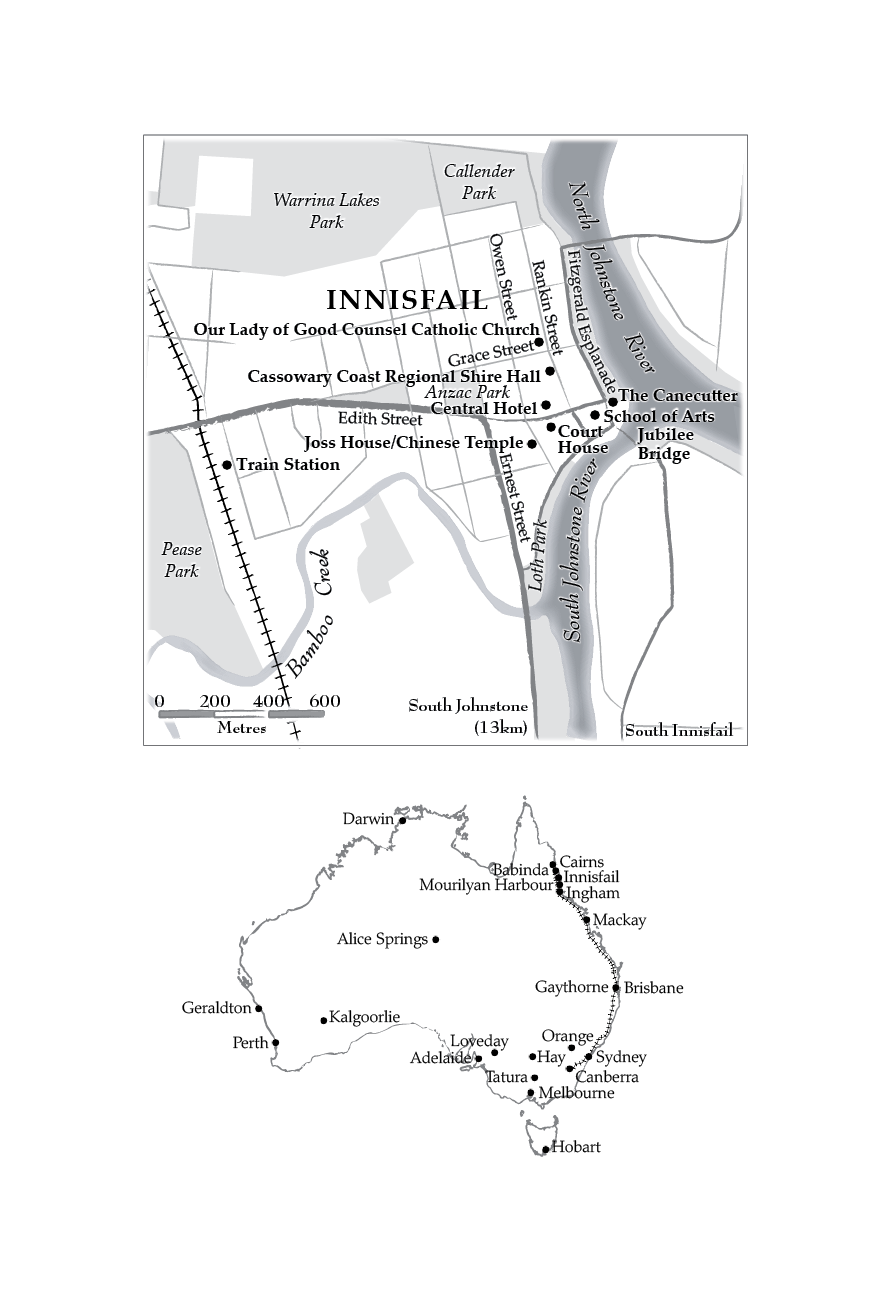

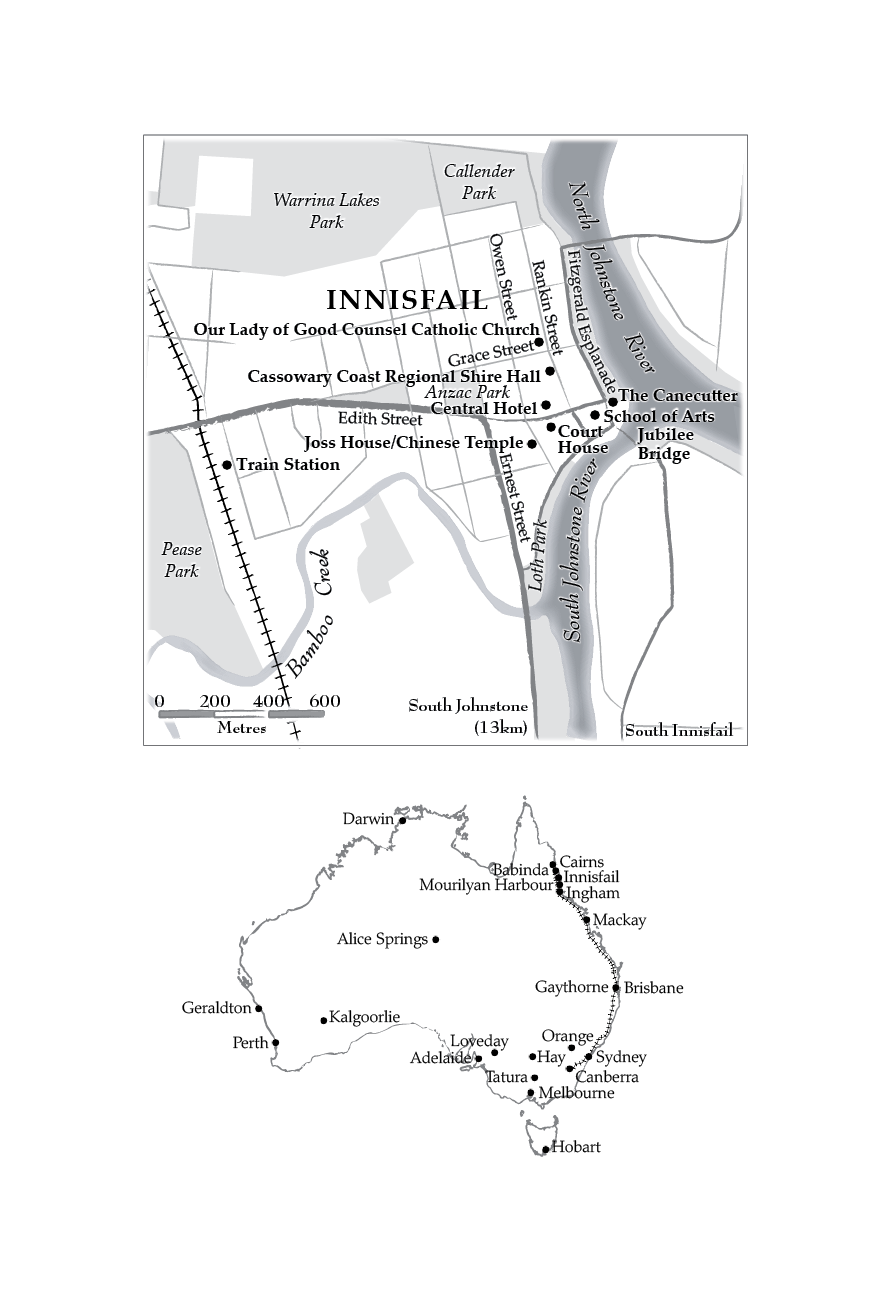

The Canberra train station looks almost deserted when my taxi pulls in to the rank. As I emerge from the back seat, the cold morning air has the effect of the first coffee of the day. Suddenly I am awake and ready for the challenge of getting from Canberra to Innisfail in north Queensland in time to see my grandmother. Inside the passenger waiting room there are a number of travellers already assembled, despite the fact the train to Sydney wont be leaving for another forty-five minutes. A few people are lined up in front of the Country Link office and so I join them in the queue, shifting my weight from foot to foot with nervous impatience.

When it is my turn to sit down at the booking desk I am in a confessional mood. I tell the Country Link lady opposite me that my grandmother my nonna is unwell; in fact, we believe she is dying and I need to see her as soon as possible. I want a ticket home to Sydney as well as a return ticket from Sydney to Innisfail. The Country Link lady doesnt comment on my revelation. Perhaps she thinks I am looking for a discounted fare, like the airlines give for emergencies and bereavements. She repeats the name of my destination to confirm she has it right Innisfail and then starts tapping away on the keyboard, her face turned intently towards the static and glow of the computer screen.

In the minute or so she spends typing I offer up another confession, namely that while the situation with my nonna is urgent, Im not one for plane travel. I tell her about my fear of flying, a phobia I developed in my mid twenties despite a childhood and adolescence spent in planes travelling around the country and the world. I am pouring my heart out but she says nothing. She just keeps typing, her only response the sound of the clicks of her varnished nails on the plastic keys. Who can blame her? There is a crazy person sitting in front of her who is desperate to get to her dying grandmother three thousand kilometres away and she is taking a train.

After a minute or two, the Country Link lady turns away from her screen to give me the computers diagnosis. I can get an overnight train from Sydney to Brisbane this evening. There is a sleeper available but I will have to share with another female.

Thats fine, I tell her. I will have a few hours wait in Brisbane and then I can catch The Sunlander , which travels from Brisbane to Cairns, stopping off at Innisfail. There are no sleepers but there are lots of first-class seats left. The good news is that on the trip back there is a single sleeper free from Innisfail to Brisbane. After another short stay in Brisbane and a bus ride over the border, I will be able to have a sleeper to myself again and I will arrive in Sydney the next morning. I will be on trains almost as long as I will be in Innisfail.

Next page