Home Below Hells Canyon

GRACE JORDAN

UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA PRESS

Lincoln and London

Copyright 1954 by Grace Jordan

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 54-6332

International Standard Book Number 0-8032-5107-6

International Standard Book Number 0-8032-0946-0 cloth

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-5107-6 (pbk: alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-5303-2 (electronic: e-pub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-8032-5304-9 (electronic: mobi)

Bison Book edition reprinted by arrangement with the author from the edition published by Thomas Y. Crowell Company

T O M Y C ANYON N EIGHBORS

Contents

Authors Note

The following account tells of the years that we spent on a sheep ranch in the Snake River canyon in middle Idaho. Place names are factual, though the time sequence has occasionally been altered for better story telling. Names of incidental characters have in a few instances been changed; but those people described as our neighbors were truly such, and life without them would have been harder and surely less delightful.

For help in establishing forgotten facts, I am indebted to Ellen Edgington and Page Hosmer, who returned old letters to me; and to Patsy, Joe, and Steve Jordan for the use of their diaries.

G RACE J ORDAN

A t five-thirty, that March morning, it was still dark and quiet and the least bit cold along Snake River Avenue, as we transferred from taxi to dock, but in the warehouse of the Snake River Navigation Company of Lewiston there was activity and light. Captain Brewrink of the packet Chief Joseph, a lean, unhurried six-footer, relieved us of our hand luggage and gave us cheerful news. Unless something happens, he said, we can make Kirkwood tonight, say sixteen hours from nowthat is, if theres moonlight.

The Chief lay rocking on the dark breast of the Snake, and we who picked our way down the gangplank together were five: my husbands father, two children, I, and the baby in my arms.

Grandpa nodded and smiled. He was a solid man of solid counsel, who never asked idle questions, and he already knew a great deal about the eighty-six miles of white water that tumbled between Kirkwood Bar, our destination, and the Lewiston, Idaho, boat dock. He had known and lived in the adjacent country for thirty years.

Thinking of the long hours ahead of us, I was thankful for the big lunch hamper I had brought. It held fruit, sandwiches, cheese, hard-boiled eggs, cookies and chocolate bars, and before leaving the hotel I had been able to buy three quarts of milk for the children. Grandpa and I would have to drink river water.

The Chief was not provisioned, and it had no berths. The captain and his helper carried big lunchboxes, thermos coffee, and their own sleeping bags; passengers could do likewise. But the children and I had already made a long train and bus trip before reaching Lewiston, and we possessed no bedding. I could not imagine how we would spend the night if the Chief had too many stops to make or if clouds blotted out the moon. The boat had no lights except kerosene lanternslights were useless for running since they only made the water opaque.

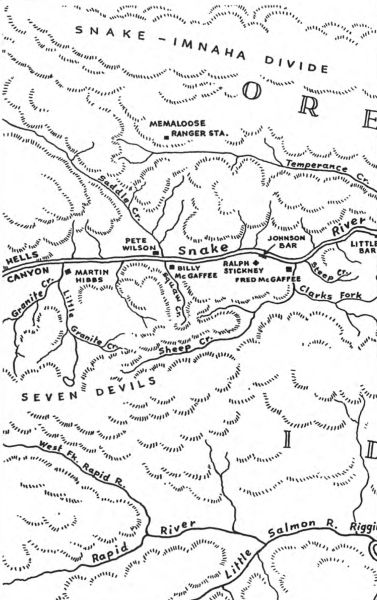

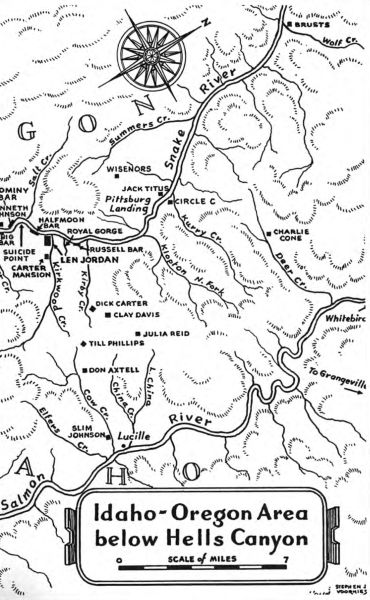

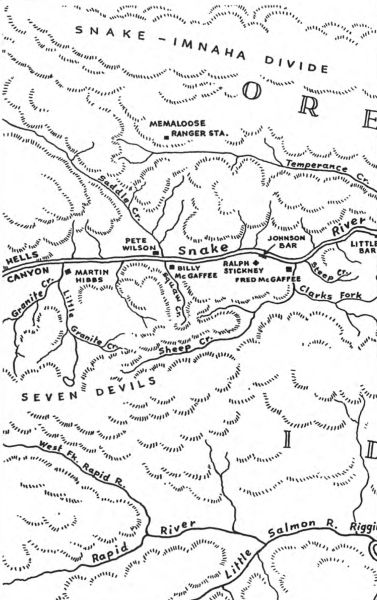

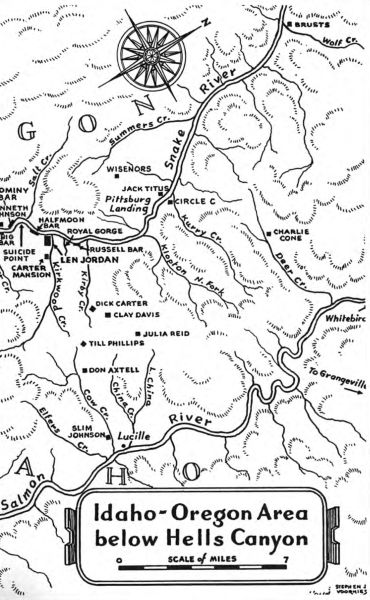

Kirkwood Bar was the sheep ranch which my husband and I, with a partner named Dick Maxwell, were buying. It lay in the Snake gorge, on the Idaho side, just below Hells Canyon, that deepest scar on North Americas face, through which the river is not navigable and where even foot travel stops. The business arrangements had been completed while I was with my parents, a days journey west of Lewiston; and though I knew something of sheep ranches, I had never seen one in the shadow of an impassable canyon.

It was spring 1933, and the financial shaking of the past three years had jolted the Jordans badly. In those years we had abandoned running our own stock and had managed for another stockman, sometimes doing on wages of less than a hundred dollars a month plus our living, and I longed to get where we could operate again for ourselves, regardless of any physical hardship such ownership might involve. I was not disturbed by the isolation one must expect at Kirkwood and the two children were almost as eager as I to reach the new place their father had described in his letters. They had seen him but once in the last six months, for he had been at the ranch since purchase was completed, carrying on in a bachelor atmosphere.

Patsy was a sturdy six, with a straight Saxon bob and candid blue eyes above enduring freckles. Everything interested her to an extreme degree. Joe, at three and a half, was faintly olive skinned, quiet, but neither passive nor defenseless. Neither of them was objectionably self-important, for we had been surrounded a great deal by hired help or had stayed with other people. Children living thus must learn that everybody has his own preferences, and these must be observed.

Steve, seven months old, had big eyes and long lashes, and one very effective tool, a wide smile. That smile had sufficed all of yesterday, on the train to Pendleton, where Grandpa joined us, and even through the long bus hours to Lewiston on the Snake.

In Lewiston, where Joe had shared his grandfathers room, we had only a short nights sleep. Before daylight we were dressed and packed so as to have breakfast and be at the dock for the six oclock departure of the boat, which made the canyon run only once a week. Breakfast did not benefit Steve much, for he was only half weaned, and the new sounds and faces in the cafe had distracted him from his cereal.

Our lunch hamper had been packed for thirty-six hours ahead of time, since I had known there might be no place or time enroute to buy suitable food. It was unthinkable to miss the weekly boat, and for two reasons. In the first place I was almost out of money; and in the second, the children and I had nowhere else to go. The failure of our bank a week before had wiped out my checking account, and I had, literally, only the money in my purse.

For traveling expenses, my mother had been able to secure twenty dollars in hard money for me; and a friend, appearing opportunely, had loaned me a five dollar bill. It looked as if we would make it to Kirkwood, where coin would buy practically nothing, but we might make it by only a neck. With gratitude I remembered that Grandpa had picked up the dinner check last night, and paid for breakfast this morning; but that was Grandpas way.

In the body of the boat we found seats on the benches running along two sides of the single compartment back of the pilothouse and serving as a step-down from the little deck. On the dock side, the canvases were rolled to admit freight and passengers. Through the slits on the other side I could get glimpses of the river as the light increased.

Here the Snake was broad and smooth, flowing down from between purple hills on the south, hills with vegetation at the waters edge but fairly bald above. On the opposite bank slumbered the little city of Clarkston, and farther down a bridge arched across between the two towns.

In the up-river coves a delicate fog floated, but beyond this and the bare hills unreality closed in, for there the stream made a bend, drawing a curtain on life above. On another trip I had been considerably above that bend, and I knew that the hills increased in steepness and that the arrogant Snake tore down between them in relentless power. But of the final barrier, Hells Canyon, where neither boats nor men but only wild animals had penetrated, of that I knew merely the stories I had heard. And Kirkwood lay just this side.

Next page