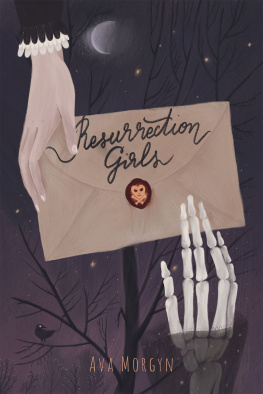

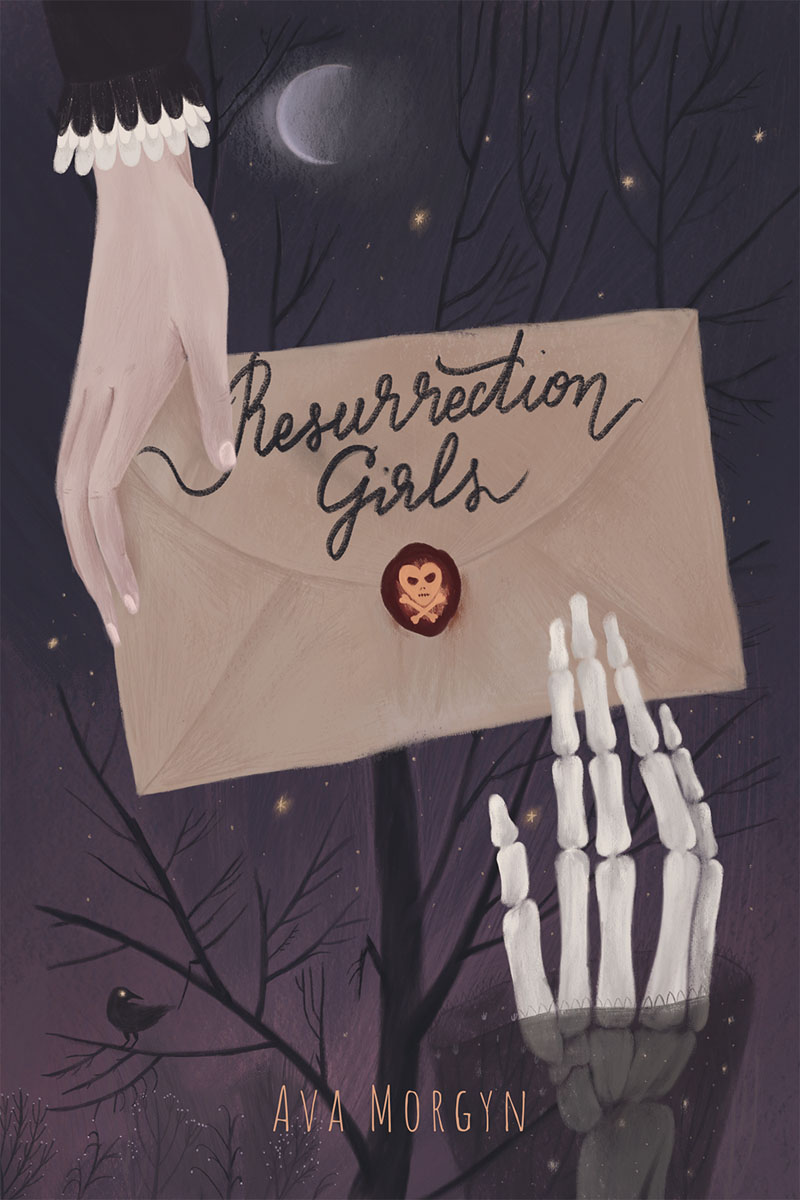

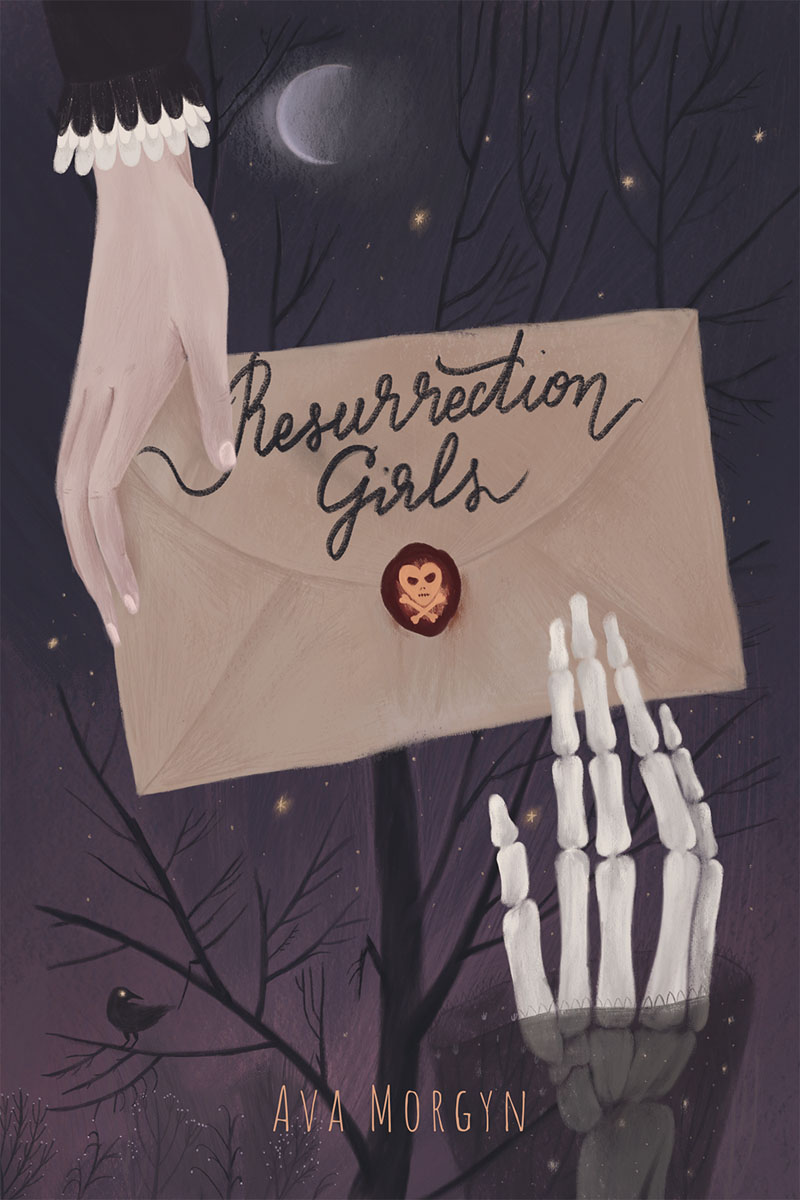

OLIVIA FOSTER HASNT FELT ALIVE since her little brother drowned in the backyard pool three years ago. She barely speaks to her father, and her mother has become the neighborhood shut-in, dulled by pills that Olivia steals and takes when she feels overwhelmed.

Then Kara Hallas moves in across the street with her mother and grandmother, and Olivia is immediately captivated by these three generations of enigmatic women. Drawn to Karas intoxicating presence, Olivia is taken in even by her morbid habit of writing to men on death row. Together, they sign their letters as the Resurrection Girls.

Kara awakens something deep in Olivia that gives her the strength to confront her familys dark unraveling. But as Kara helps her take steps to reconnect with her parents, Olivia realizes that her new friend is touched by a different kind of darkness. The Hallas women embody something strange, magical, and deadlyand Olivia has enough experience with death to know its pulling her in.

Albert Whitman & Co.

100 Years of Good Books

www.albertwhitman.com

Printed in the United States of America

Jacket art copyright 2019 by Albert Whitman & Company

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Text copyright 2019 by Anna Sweat

Hardcover edition first published in the United States of America in 2019 by Albert Whitman & Company

ISBN 978-0-8075-6942-9 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8075-6941-2 (ebook)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 LB 24 23 22 21 20 19

Cover artwork by Anastasiia Rafaienko

Design by Morgan Beck and Aphelandra Messer

For more information about Albert Whitman & Company,

visit our website at www.albertwhitman.com.

100 Years of Albert Whitman & Company

Celebrate with us in 2019!

For Evelyn.

We are one heart.

CHAPTER 1

The summer they moved in was the hottest on record since 1980. June, July, and August raged with hundred-degree days and the kind of steam-pot humidity Houston had come to be known for. Despite the wall of urban perspiration that greeted every citizen at every door, every morning across the city, we were knee deep in an unprecedented drought that had meteorologists twittering like canaries in coal mines. Looking back, maybe I should have known. Maybe the heat and the droughtthe boilwere all signs, if you believe in such things. By then, however, by that desperate, cloying, relentless summer, my family had ceased to believe in anything.

It was three years to the day that the moving truck pulled into the cracked, weed-ridden driveway across the street. There was something wrong with June 9. Something that set that day apart from others. Something that caused it to stew in its own juices. A day of ferment. Three years before, on that same fated date, my three-year-old brother had drowned in our backyard pool. My parents had since had it filled ina great, devastating show of jackhammers, wheelbarrows, and truck beds full of soil. The final act in a tragic play we were now trapped in. The closing curtain: a layer of fresh-laid sod. Our yard was now a giant grave to all the memories we would deny, all the words we refused to speak.

You could never trust a day divisible by that many threes.

And so, when their sixteen-foot moving truck pulled in across the street with Haul It Your Way plastered down the side in faded orange-and-blue letters, I should have known a mountain of shit was coming our way. I should have seen the cracks beginning to mark the dam and read our fate in their design. But it was hard to see past the curtain wed closed over our lives, past the green lawn, where my little brother had once played and died, past the giant oak withering in our front yarda testament to summers brutalitypast the smothering heat and the suffocating grief that surrounded us like the ash of Pompeii. Its a wonder I noticed them at all.

Of course, they were pretty hard to miss. From the beginning, there was something separate about them. They and June 9 deserved each other.

I was sixteen, with no car, which meant I was trapped inside the hollow, ringing, soulless structure we once called home. School was out, and without my studies to throw my energy and attention into, I was restless. I prowled. I stirred within the confines of our house with dust motes for company. My mother was upstairs in her room, locked behind her blackout curtains, wandering the land of the dead in a haze of OxyContin and Xanax. Thats what she paid the ferryman withprescription drugs. At best, they made her absent. At worst, they made her mean. My dad waswell, he was out. In truth, I didnt know where he was when he wasnt at work and wasnt at home. Neither my mom nor I did. He was just gone mostly. And when he was home, he wasnt present, so it didnt matter.

That house across the street had been vacant for years. It was a foreclosure. A Victorian wannabe with wood siding and a wraparound porch that made it seem older than the other houses on our street. The last family whod lived there, a widowed mom with four kids, whose husband hung himself in the master bedroom, left it completely trashed inside. Once when I was a kid, long before Robby died, my mother used her real estate license to get the code on the lockbox. Curious and nosy, we let ourselves in and looked around.

Shame, shed said, running her squared nails over holes in the Sheetrock and gouges in the countertops. Mom was polished then. Professional. I watched her key in the code and used it to sneak back in. I would dare myself to go up to the master bedroom, get as high as the top step on the staircase, then the moment Id hear a noise of some kinda squeak or a groango running back out again.

We thought the tragedy and the banks high asking price had rendered it untouchable. That was before we understood the ease with which tragedy could strike, before our own personal family tragedy blossomed like a corpse flower in our midst. Now, the two homes squared off across from each other, both vacant for all intents and purposes. Both haunted by their own ghosts.

Until they moved in.

Three women. Correctionthree generations of women. A single mom, her daughter, who looked roughly my age, and the rheumatic grandmother, blind in both eyes and frail as bat bones. I watched them unload the moving truck from between the blackout curtains in my mothers room, her gentle, drug-induced snores sounding like prayer bells. The women watched as their movers hauled mattresses and vanities, potted plants and marked boxes in through the front door. I wondered if they knew the truth about this place, about the man who swung from their rafters and the ghost of a family buried in the yard across the street.

Mostly, I wondered what they were like. The old woman stood on the front porch smoking a cigar, craning her clouded, sightless eyes up to the window where I watched, as though she could smell me. Behind her, the daughter loitered in the open doorway, leering at the moving guys, her crop top barely covering the underside of breasts far more developed than my own. And the mother failed to notice or care. She smiled, the look radiant and full of an eastern wind that had long since drifted from our sails. What was it like to smile in the face of tragedy? To look at the wreckage and seepossibility?

Next page