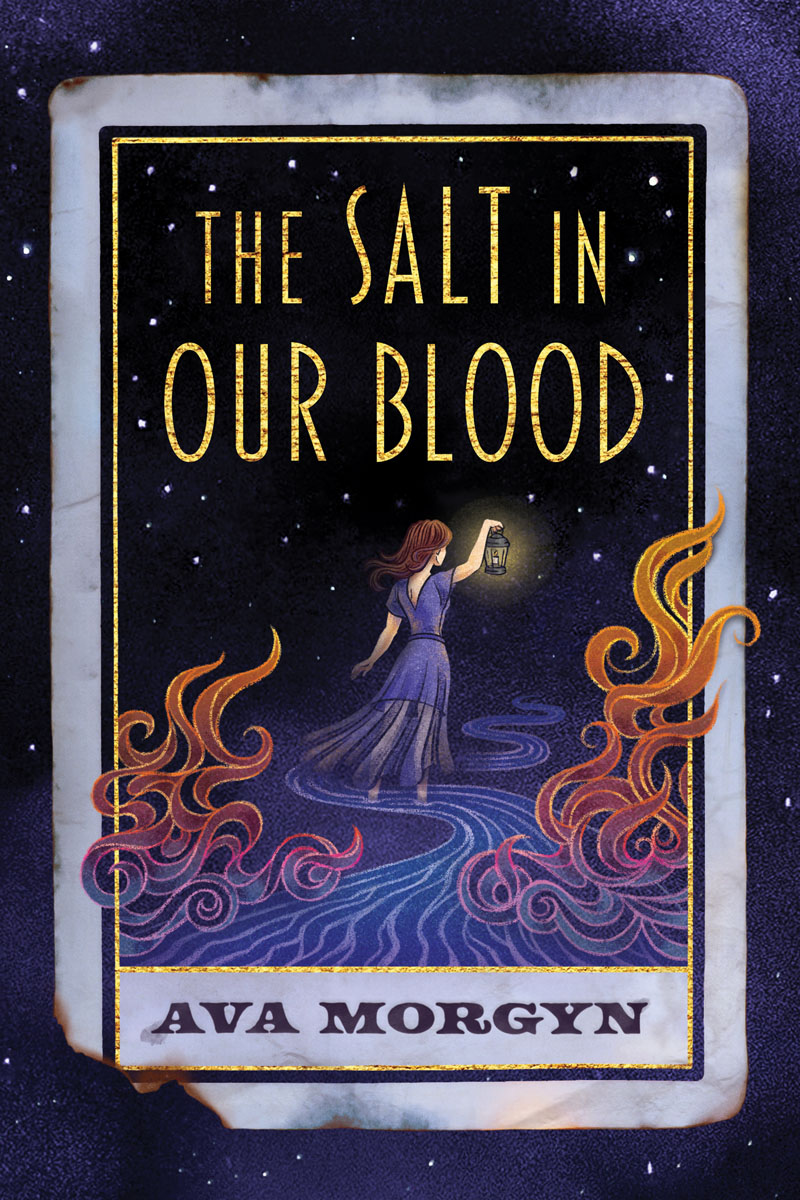

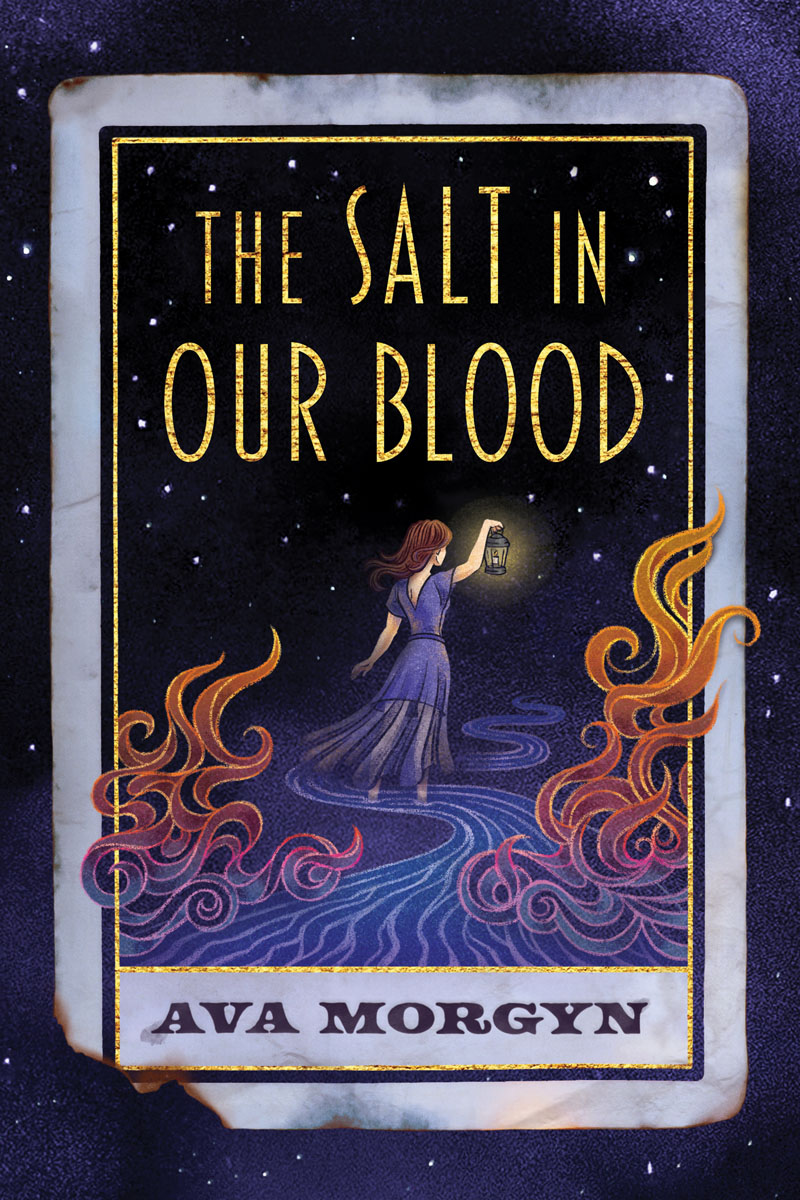

YOU CANT OUTRUN THE STORY THAT IS YOU.

Ten years ago, Cats volatile mother, Mary, left her at her grandmothers house with nothing but a deck of tarot cards. Now seventeen, Cat is determined to make her life as different from Marys as possible.

When her grandmother dies, Cat is forced to move to New Orleans with her mother. There she discovers a picture of Mary holding a baby thats not her, leading her to unravel a dark family history and challenge her belief that Marys mental health issues are the root of all their problems.

But as Cat explores the reasons for her mothers breakdown, she fears she is experiencing her own. Ever since she arrived in New Orleans, shes been haunted by strangely familiar visitorsin dreams and on the streets of the French Quarterwho know more than they should.

Unsure if she can rebuild her relationship with her mother, Cat is realizing she must confront her past, her future, and herself in the fight to try.

Albert Whitman & Co

More than 100 Years of Good Books

www.albertwhitman.com

Printed in the United States of America

Jacket art copyright 2021 by Albert Whitman & Company

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Text copyright 2021 by Anna Sweat

First published in the United States of America in 2021 by Albert Whitman & Company

ISBN 978-0-8075-7227-6 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-8075-7229-0 (ebook)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 LB 24 23 22 21 20

Cover art copyright 2021 by Albert Whitman & Company

Photography sourced from Unsplash (@domediocre, @nikhilmitra, and @yonkoz)

Cover artwork and book design by Aphelandra

For more information about Albert Whitman & Company, visit our website at www.albertwhitman.com.

For my mother, Ruth, and her mother, Mary, whose own story of estrangement inspired this book, and all the women who challenged me to be a better, more compassionate version of myself.

I.

I HAVE NEVER SEEN A DEAD PERSON BEFORE.

As I stand in the doorway of my grandma Moonys room, this thought floats across my mind. But her lifelessness is unmistakable. Something fluid has left her limbs, and they lay rigid at her sides. I cant say exactly how I know that without touching them. I am simply aware of an unyielding quality that wasnt there before. Her mouth is open, but her jaw is set at an odd angle. She must have been snoring again. Her lips are white, like bleached cotton. I look for the telltale signs of breathing, using my own pounding heartbeat as a measure, but there is no rise or fall of her chest beneath the sheet. Her eyes are closed as if in sleep, but even without the gruesome stare, I know shes no longer here.

And of course, there is the fact that Moony is always up before the sun. Her alarm clock on the nightstand reads 8:30 in harsh, red, block numerals. I stare at the numbers until my eyes glaze over and my vision blurs. They remind me of something Ive misplaced since standing herea flash of scarlet in my dream. The dream that woke me up. A dream of skeletal men riding skeletal horses through a forgotten battlefield, their red sashes blazing under a merciless sun, their black flags waving in a hot wind. Death on parade.

I blink and rub at my eyes. I fold my arms over my chest, willing the night terrors away. I dont like to entertain fantasies, good or bad, give them room to breathe and grow, to spread like mold across the wrinkles of my mind. Moony always said an overactive imagination is just another gateway to sin.

She is as still and blank as paper. I cannot bring myself to step into the room.

I cannot go to her.

It occurs to me that I should be sad. That I should scream or cry or express some deep and troubled emotion. After all, Moony has practically been a mother to me for the last ten years. She wont be here now to watch me graduate from college with a sensible degree, or remind me that art should have a point, or ground my wilder tendencies. But all I feel is a vacancy where the sadness should be and a brutal clarity that makes everything around me look sharper and brighter than normal. Like the faded, yellow-floral curtains pulled across her picture window that seem as though theyve been drawn on with a highlighter. Or the edge of her cotton lampshade, where every speck of lint is rising like the hairs along my arm. As though this moment when my grandmother has died is more real than any other moment in my short life. Being just this side of seventeen, I would assume that there will be more moments like this one, more violently alive moments. And yet, I dont believe it standing here.

I think this is the first time Ive ever really seen Moony. Really noticed her sagging breasts like paperweights rolling off her ribs and the patches of white-pink scalp that show through her short hair when she doesnt have it combed just right. I think this is the biggest impression Moony has ever left on methe biggest impression life will ever leave on me. But I suppose this impression doesnt belong to life at all.

The carpet is like burlap against the soles of my feet, but the seam at her doorway wont permit me to pass. There are things one should do in a moment like this. Words to be spoken. Authorities to be alerted. Affairs to put in order. I know nothing about Moonys affairs, except the scattered bits she told mesocial security every month, an account somewhere with money saved for my college, paper bills that come in the mail every week and get sorted into stacks on her desk in the hall. Im not sure anyone knows more. But as I am the only one here, I realize it falls to me to take the proper steps.

My stomach rumbles beneath the oversized SeaWorld T-shirt I slept in. Is it wrong to think of food when you just found someone you love dead? There is a definite not-rightness about it. But I cant say its completely wrong. Im not sure my stomach has gotten the message that Moony has died. Clearly my heart hasnt, so how could my stomach? Only my brain is online right now, and its not telling anyone else. Not yet.

I contemplate having a bowl of cereal while I figure out what to do. I should make a list. Moony was always making listsgrocery lists, to-do lists, lists of weekly sins she needed to share in confession. She was big on lists. Lists provided structure, and she was big on structure. She would like it if I made a list about her. I register a small sting of emotion at this thought, but it doesnt sink deeper than my clavicles, like a piece of ice lodged in the throat. Uncomfortable, sure, but you can still swallow around it.

I walk to the kitchen and take the magnetic pad of paper off the fridge. I decide cereal can wait. It would look wrong if I ate first. Moony always believed someone was watching. Mostly God. And not in a kindly, mother hen sort of way. More in a devious, gotcha sort of way. God was watching Moony, and Moony was watching me. Im not watching anyone.

I sit at the table, the vinyl seat sticking to my naked thighs, and begin. I write #1.

With any plan of action, something always comes first, but its not obvious to me what that would be. Its here that I realize Im not thinking clearly. My brain may be online, but its not running on all cylinders. Even my metaphors are confused. I try to imagine myself as someone else, a total stranger. What would that person do if they found their grandmother dead? My stomach rumbles again, and all I can think about is cereal, but I refuse to eat.

Next page