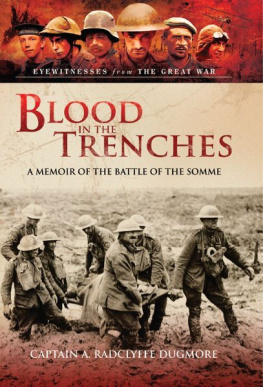

C hests swelled with patriotic fervor. Young men in Germany, France, and Great Britain rushed to enlist. Children, wives, and sweethearts lined the streets as ranks of their proud soldiers marched to railway stations, where troop trains waited to carry them to the front in France and Belgium.

Soldiers tucked pictures of their loved ones in their pockets, and many packed prayer books in their bags. As young men marched by, teenage girls darted into the streets to tuck flowers into the barrels of their rifles. Most of these soldiersas well as their sweethearts, their mothers, and their governmentsbelieved theyd be safely home in time for Christmas.

At first, enthusiasm for combat ran high as old soldiers made battle plans and young soldiers enlisted to carry them out. Both sides expected the war to be short. But lightning fast, the Great War became a nightmare of blood and death in the trenches across Europe.

The governments and their generals were incredibly shortsighted. Soldiers on horseback were no match for machine guns and rapid-fire field artillery, both innovations since Europeans last battled in the 1880s. When the snow flew along the battle line of the Western Front, it became midnight clear that no one was coming home for Christmas.

Copyright 2016 by Kerrie Logan Hollihan

All rights reserved

First edition

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-130-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data

Are available from the Library of Congress.

Interior design: Sarah Olson

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

In memory of my grandfather

Frederick Urban Logan

US Army soldier and bugler in France

19181919

CONTENTS

This map depicts Europe at the outbreak of World War I.

Department of Art and Military Engineering at the U.S. Military Academy

PREFACE

COME AND DIE

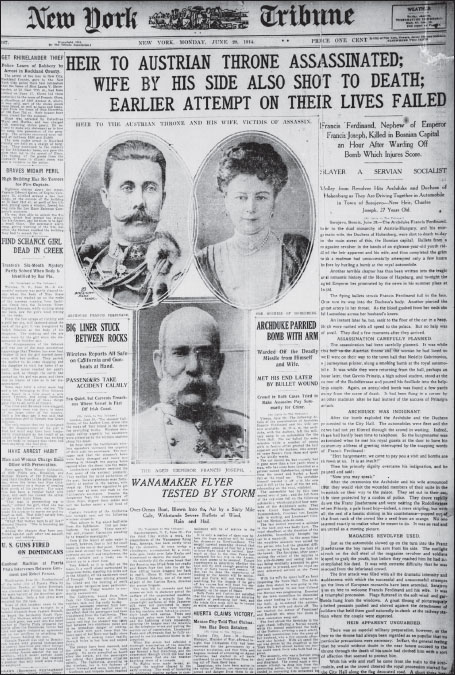

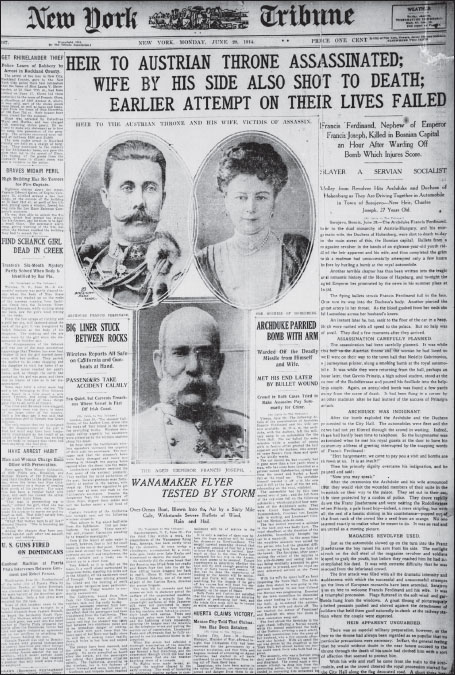

O n Monday, June 29, 1914, newsboys on American and European streets shouted headlines to passersby with reports of an assassination far from home. The heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary was dead.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Duchess Sophie, were making a state visit to Sarajevo, Bosnia, a tiny province under the empires control. As their open car rolled through Sarajevo, a 19-year-old Serbian revolutionary named Gavrilo Princip ran into the street and shot the couple point-blank. Princip, who dreamed of independence for his fellow Serbs, had no idea that he had set off a world war.

Most Americans and many Europeans didnt dwell on the killings. Bosnia, tucked into the southern end of the vast Austro-Hungarian Empire, seemed like a remote, unimportant spot. Ordinary Britons, French, and Germans had their own lives to think about. It was summertime, when young folks enjoyed a welcome break from their long, dark winters. Irne Curie, a French student who studied science at the Sorbonne in Paris, looked forward to her vacation at the seaside. A British university student, Ronald Tolkien, was writing letters to his fiance and inventing a fanciful language he named Elvish. A German student, Walter Koessler, was deep into architecture classes at his university.

S HOT TO D EATH, proclaims the June 29, 1914, headline in the New York Tribune, reporting on the assassination of an Austrian archduke, the act that ignited World War I. Chronicling America, Library of Congress

Across the Atlantic, Americans read the news, too, but many of them had never heard of Bosnia or Serbia and knew little if anything about the imperial family of Austria-Hungary. Central Europe was very far from homethe voyage by sea alone from New York to the coast of France took more than a week. Proud to be citizens of a nation that had overthrown its king, Americans liked their independence and stayed wary of foreign entanglements, as President George Washington had advised so long ago. The United States and its people had no plans to entangle themselves in a European war.

That June, young Americans were enjoying the summer. A high school sophomore, Ernie Hemingway, was working a job at his familys summer home in the woods of Michigans Upper Peninsula. Quentin Roosevelt, the 17-year-old son of a former US president, had friends coming to celebrate the Fourth of July with his family at Oyster Bay, New York. Buster Keaton, at 19, was a veteran comic making people laugh on New Yorks vaudeville stages. A Colorado cowboy named Fred Libby was working as a farmhand north of the border in Calgary, a city in western Canada. The troubles of European nations and their kings and emperors didnt matter to any of them.

No one could have predicted that in three years Ernie, Quentin, Buster, and Fred would be on European soil fighting for their lives. Irne, Ronald, and Walter would see war in France much earlier.

On July 28, 1914, exactly one month after Gavrilo Princip shot Franz Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia and set off a massive chain reaction that exploded into the Great War, what we now call World War I. There seemed to be no turning back, because Europes nations were caught up in a tangled web of alliances. When one country went to war, the other members of its partnership followed suit.

Austria-Hungarys declaration of war lit a ring of fire that spread through much of Europe and the Middle East. Russia, allied with Serbia, mobilized its army on July 31 to fight the Austrians. On August 1, Germany, bound by treaty to Austria-Hungary, declared war on Russia to the east. On August 3, Germany declared war on Russias ally France to the west.

By August 4 the German army was rolling across Belgium, a neutral nation, on its way to invade France. Across the English Channel, Great Britain, obligated by treaty to defend Belgium, declared war on Germany that same day. On August 6 Austria-Hungary declared war on Russia.

In just ten days, the ring of fire was fully lit. The imperial giants of Great Britain, France, and Russia aligned their forces to become the Triple Entente, soon known as the Allies. Japan joined them, and later, Italy. Germany and Austria-Hungary formed the Central Powers, aided by Turkey and Bulgaria. As global empires, each of these nations counted on its colonial armies to join them in battle. In the end, 32 countries fought in the Great War.

Chests swelled with patriotic fervor. Young men in Germany, France, and Great Britain rushed to enlist. Children, wives, and sweethearts lined the streets as ranks of their proud soldiers marched to railway stations, where troop trains waited to carry them to the front in France and Belgium.

Soldiers tucked pictures of their loved ones in their pockets, and many packed prayer books in their bags. As young men marched by, teenage girls darted into the streets to tuck flowers into the barrels of their rifles. Most of these soldiersas well as their sweethearts, their mothers, and their governmentsbelieved theyd be safely home in time for Christmas.

Next page