I would like to acknowledge the support and co-operation of the following individuals and organisations/institutions in the preparation of this book

Nick Arber; Stephanie Bennett, Royal Warwickshire Regimental Museum; Reverend Nigel Cave; Dr Roger Custance, Winchester College; Lt Colonel C D Darroch, Royal Hampshire Regimental Museum; Peter Donnelly, Kings Own Regimental Museum; Lt Colonel John Downham, Queens Lancashire Regiment; Lt Colonel David Eliot, Somerset Light Infantry Regimental Museum; Norman Gray; Frederick Hackett; Gordon Hawkesworth;

John & Sheila Iles; Amanda Mareno, Royal Irish Regimental Fusiliers Museum; Emma Renshaw; Helen Renshaw; Julie Renshaw; Dr John Robb; Colonel Jack Sheldon, Queens Lancashire Regiment; Karl Simpson; Gary Smith, Museum of the Queens Lancashire Regiment, Michael & Frances Speakman; Liz Tait; Kyle Tallett; James W Taylor; Robert Thompson; Roni Wilkinson, Pen & Sword Books; Yousef Al-Shawa; The British Newspaper Library; The Imperial War Museum; The National Archives.

CHAPTER ONE

1 JULY 1916

There was some optimism on the eve of the battle. Surely, nothing could survive the massive bombardment that had been inflicted on the enemy positions. Some troops were told to walk over No Mans Land, carrying their rifles at the port position pointing into the sky and there seemed no reason to leave essential equipment behind, so many were loaded up with picks, shovels, barbed wire and other consolidating gear.

After all the rain, the day was fine and sunny, just right for a stroll after being cooped up in the trenches for days on end. Among the men of the 4th Division were some survivors from the original British Expeditionary Force, described by the German high command as that contemptible little army whose losses had then been made up by Territorial troops. However, subsequent drafts of Kitcheners new army recruits meant that for the most part the battalions involved bore no resemblance to their well trained predecessors.

The divisional formation was as follows:

10 Brigade :

1/R.Warwicks; 2/Seaforth H; 1/Royal Irish Fus. 2/R. Dublin Fus.

11 Brigade :

1/Somerset LI; 1/East Lancashire; 1/Hampshire; 1/Rifle Brigade.

12 Brigade :

1/Kings Own; 2/Lancashire Fus; 2/Essex; 2/Duke of Wellingtons. Close by, on the right of the divisional sector on the other side of the Beaumont-Auchonvillers road and on the left of the 29th Divisional sector, preparations had been made to blow a massive mine that had been laid under the German position known as the Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt and it is worth considering the effect of this plan and its consequences. The 252 Tunnelling Company of the Royal Engineers had dug a tunnel from a forward trench named Pilk Street and placed 40,000 pounds of ammonal in a chamber at the end of it. How to proceed with this feat of purely manual labour was, though, of some dispute. Lieutenant-General Sir A G Hunter-Weston, commanding VIII Corps, originally intended to blow it some hours before zero, occupy the crater, which would be in No Mans Land, and let the commotion die down before the main assault. In this way, it was hoped that the Germans would not be alerted to the imminent attack. Sir Douglas Haig, though, after consulting with the Inspector of Mines, overruled this, stating that the armys record at this tactic was poor while, by comparison the Germans were very adept at occupying craters and holding on to them. In all likelihood it would be the Germans who would be in possession of the position at zero hour. It had previously been ordered by Fourth Army Headquarters that all mines on its front should be exploded between zero and eight minutes before zero. Hunter-Weston, probably in a show of defiance, then suggested ten minutes before zero, though what difference two minutes would make is not clear, apart from face saving. There was then some concern that the fallout from explosion would land on the attacking troops. However they would have had to have been lying out very close to the German lines for this to occur as it was already known from previous operations in Belgium that debris falls to the ground very quickly, at the maximum after about twenty to thirty seconds.

A British 9.2 gun on a railway mounting.

There was, then, the question of the artillery. This would have to lift in time to allow the assaulting troops to occupy the crater without hindrance. There was, though, to be more controversy. It was decided that all the heavy artillery in the entire 29th Division sector should lift from the front line at 7.20 am and shell the German reserve positions. There they would be joined by the howitzers, who were firing on the German second line, at 7.25 am. The small 18 pounder guns were ordered to reduce their fire by half at three minutes before zero. Thus, the Germans were forewarned and left largely unhindered to face their attackers. The diary of the VIII Corps Heavy Artillery states that the barrage lifted at 7.20 am and 7.25 am in accordance with operation orders but many infantrymen claimed it lifted earlier than that. Later, though, no copy of the orders could be found.

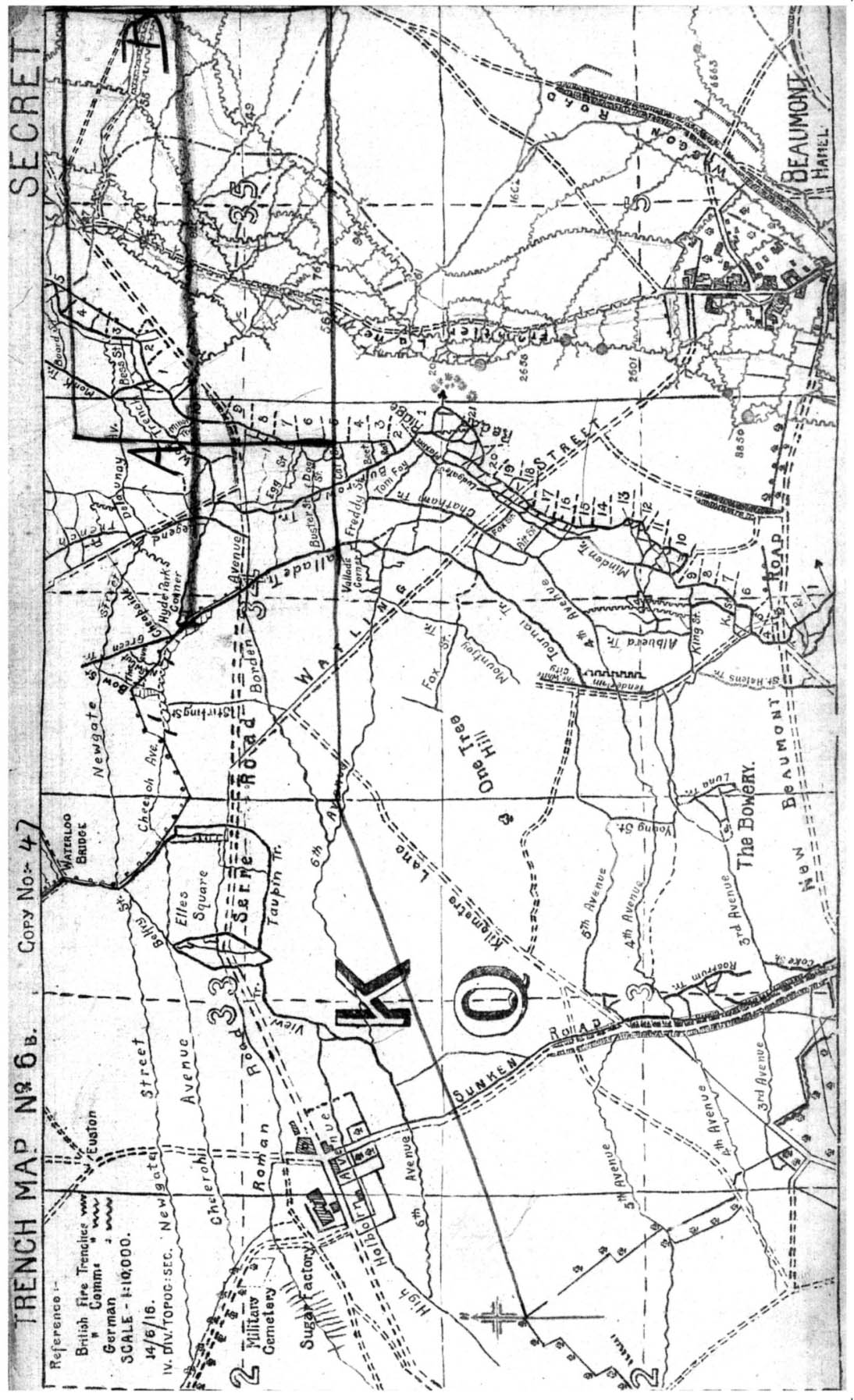

MAP 1. RELATIVE BRITISH AND GERMAN FRONT LINES ON REDAN RIDGE 1 JULY.

The men of the 4th Division, on the right of their sector on the Redan Ridge, could have had a grandstand view of the events as they unfolded while they waited for their attack to commence. They would have seen two platoons of the 2/Royal Fusiliers rush forward with four Lewis guns and four Stokes mortars. They were greeted by heavy machinegun and rifle fire, and many were casualties before they reached the crater. Nevertheless, at least two Lewis gun positions were set up, one at each end of the crater, where they hung on. Eventually, they were driven back and later the Germans were seen out in No Mans Land making downward thrusts and it is thought that they were bayoneting the wounded.

A German account stated:

During the bombardment there was a terrific explosion which for a moment completely drowned the thunder of the artillery. A great cloud of smoke rose up from the trenches of no. 9 company, followed by a tremendous shower of stones, which seemed to fall from the sky all over our position. More than three sections of no. 9 company were blown into the air, and the neighbouring dugouts blown in and blocked. The ground all around was white with the debris of chalk as if it had been snowing, and a gigantic crater, over fifty yards in diametre, and sixty feet deep gaped like an open wound in the side of the hill. The explosion was a signal for the infantry attack, and every one got ready and stood on the lower steps of the dugouts, rifles in hand, waiting for the bombardment to lift. In a few minutes the shelling ceased, and we rushed up the steps and out into the crater positions. Ahead of us wave after wave of British troops were crawling out of their trenches and coming forward towards us at a walk, their bayonets glistening in the sun. (Reserve Regiment 119)

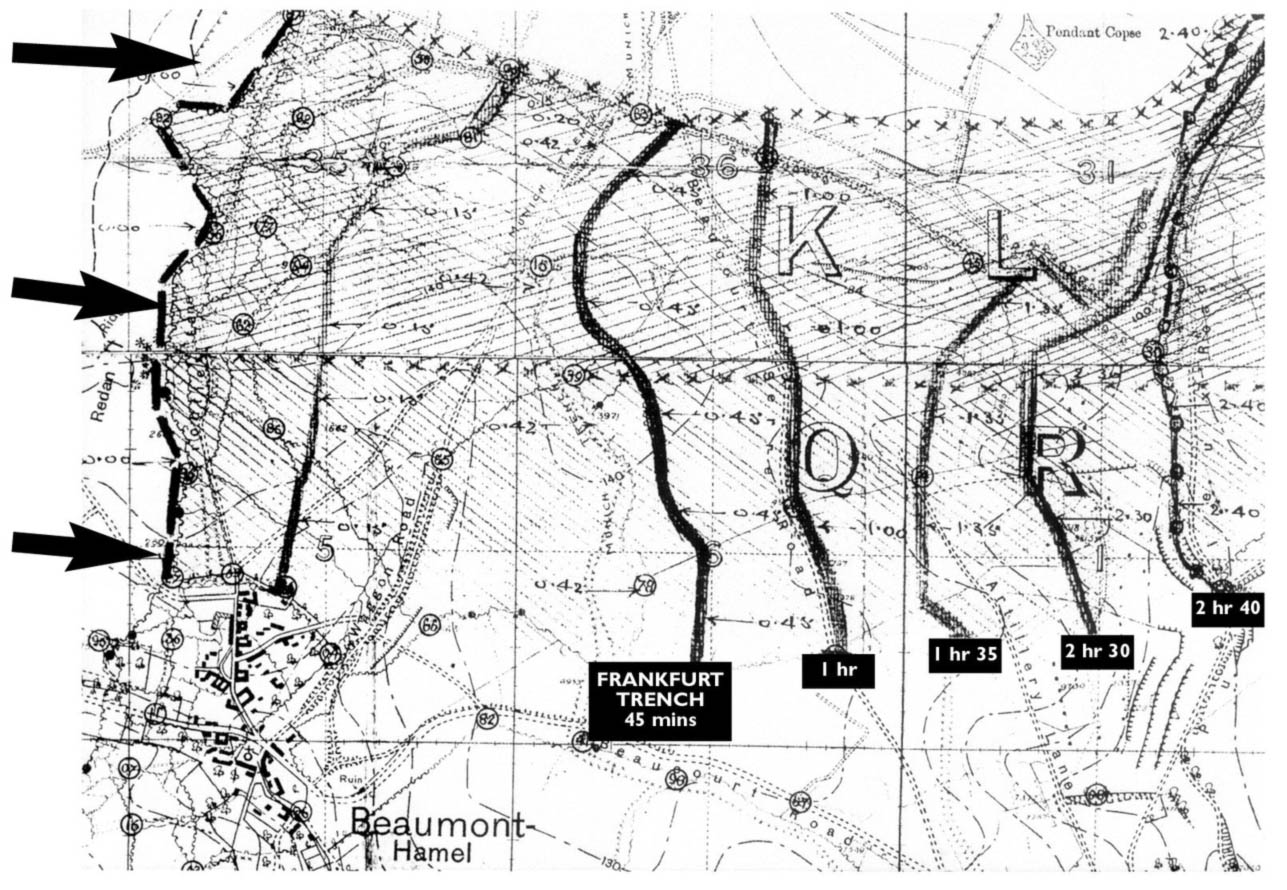

Map 2. SHOWING THE OBJECTIVES AND TIMINGS FOR 4 DIVISION 1 JULY. NOTE THAT FRANKFURT TRENCH WAS TO BE CAPTURED AFTER 45 MINUTES.

(Taken from original colour coded map)