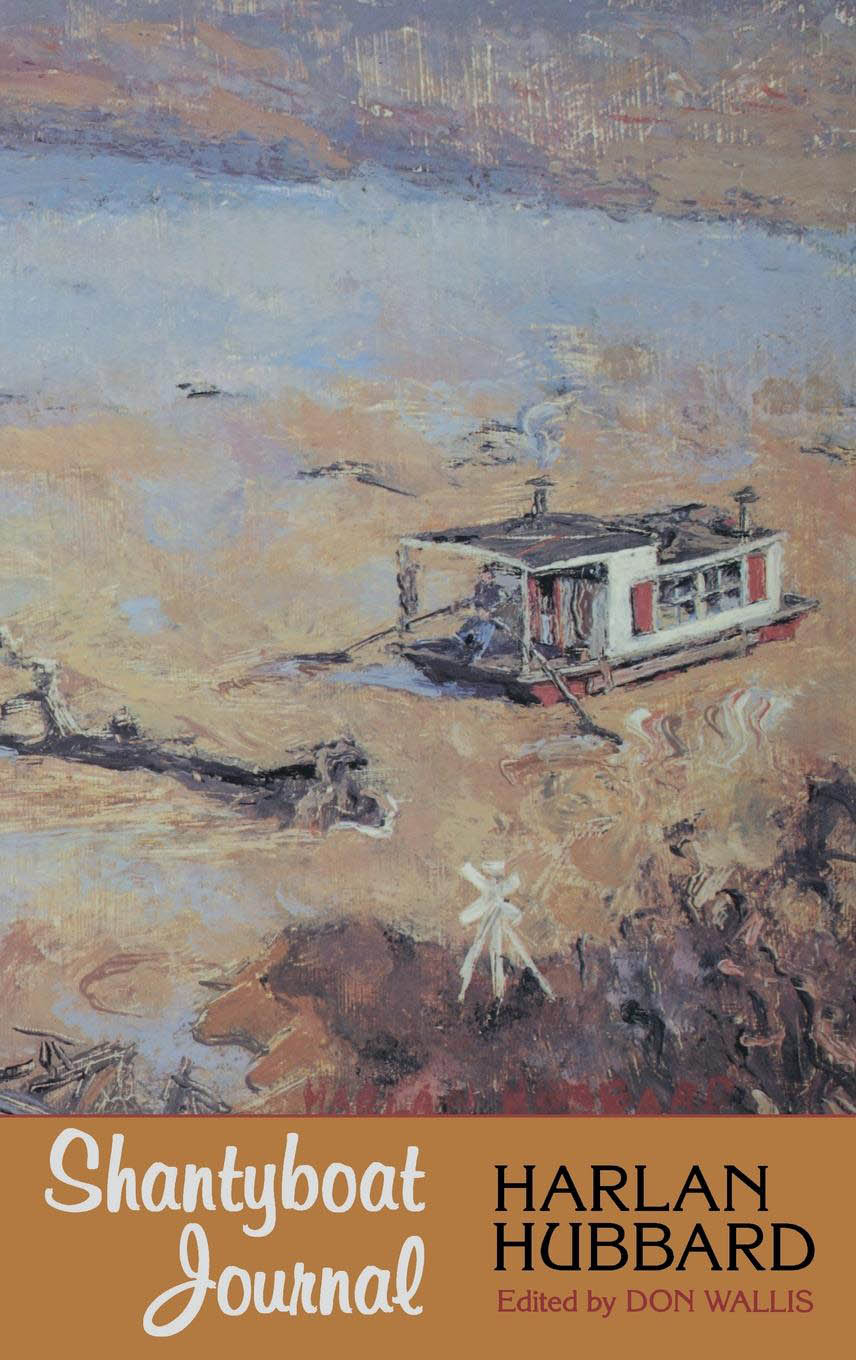

Shantyboat Journal

My river is the Ohio, whose channel from the first has borne the dreams of men....

... To live with the river, to watch it through the changing seasons, to go with it on its long journey to the sea.

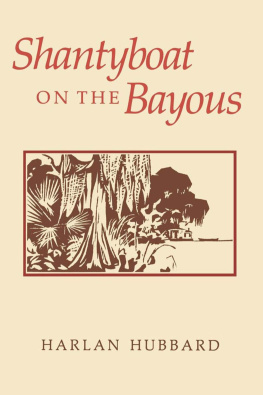

Shantyboat

Shantyboat Journal

Harlan Hubbard

with illustrations by the author

Don Wallis, Editor

Copyright 1994 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine College, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Club, Georgetown College, Kentucky

Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

Editorial and Sales Offices: Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hubbard, Harlan.

Shantyboat journal / Harlan Hubbard ; Don Wallis, editor ; with illustrations by the author.

p.cm.

ISBN 0-8131-1868-9 (acid-free paper) :

1. Mississippi RiverDescription and travel. 2. Ohio RiverDescription and travel. 3. BayousLouisiana. 4. Shantyboats and shantyboatersMississippi River. 5. Shantyboats and shantyboatersOhio River. 6. Hubbard, HarlanDiaries.I. Wallis. Don, 1943-.II. Title.

F 354.H73 1994

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Contents

Editors Preface

Harlan Hubbard was a thorough keeper of his journal. He wrote an entry, usually a long entry full of details, for almost every day during the Shantyboat Journal years. He kept his journal in a series of hard-backed notebooks. The hard backs of these books were useful, for Harlan rarely had a table or desk to write on; he often wrote while sitting on the deck of the houseboat as it drifted, or in the johnboat as he fished. Every once in a while his pencil point makes a sudden wavy squiggle on the page, thanks to the rocking of the boat or a fish biting on the line.

Harlan had started keeping his journal in 1929, inspired perhaps by the journals of Thoreau, a great influence on his life. He kept his journal regularly until 1968. Keeping his journal was of essential importance to Harlan, as a way of examining his life; he had no thought of putting it to any other purpose. But he discovered another use for his journal when, having suffered an attack of appendicitis during the Mississippi River stretch of his shantyboat journey, he found himself in a hospital for a five-day stay. The five days passed quickly enough, Harlan recalled in Shantyboat. Desirous of turning them to account by producing something positive, some fruit which would not have ripened in ordinary times, I began the writing of this narrative of our river life. He used his journal as the basis for Shantyboat and its sequel, Shantyboat on the Bayous, and, later, for Payne Hollow.

The journal books were stowed away in the attic of the Hubbard home at Payne Hollow One day a visitor, Vince Kohler, discovered them and, after Harlan read a few passages to him, recognized their value. He had them typed, and Harlan and Anna reviewed the nearly million-word typescript, correcting it and making a fewa very fewchanges in wording and phrasing. Vince Kohler and David Ward then edited the first sixteen years of the journals, and Harlan Hubbards Journals 1929-1944 was published in 1987 by the University Press of Kentucky.

In editing the Shantyboat Journal I have tried to preserve a sense of the unfolding of a story, as well as Harlan's day-by-day recording of his vision of the world. For the storys sake I have organized the material into sections and chapters and have given them titles, and I have inserted here and there in the text passages from Shantyboat and Shantyboat on the Bayous to provide some continuity and to reinforce or extend the meanings of events and observations. I told Harlan I would do this, and he approved; my goal was to edit the text in a way he would like, and I believe he would have liked it.

Harlan would have had one complaint, though. He had forgotten (he told me this) how glorious the journals were; when they were freed from his attic and he read them anew, he felt every word in them should be published. But that would have required a book of too many pages, so I have had to edit out several thousand words. It was a vexing job, for I found meaning in nearly all of those words. For those who would like to read Harlans journals complete and unedited, they are preserved, in both handwritten and typewritten form, in the University Archives at the University of Louisville, where there is an extensive collection of Hubbard materials. In making the deletions, I did not always use the customary ellipsesthree or four dotsfor to do that would have inflicted upon the pages black dots swarming around like flies, unacceptable in a book by Harlan Hubbard, a wild and natural soul but a very neat and orderly man, who valued simplicity above all.

Introduction

Sometimes I long to write a river book, Harlan Hubbard wrote in his journal on September 4, 1939, a book of the Ohio, which shall itself flow through the pages, and the very smells and sounds shall be there, too. For so it flows through my heart....

When Harlan wrote this he was thirty-nine years old, a solitary soul, restless and lonely, an artist frustrated at the failure of his work to gain recognition. He lived with his widowed mother in Fort Thomas, Kentucky, a suburb of Cincinnati, making his living by working part-time as a carpenter. He longed for a new life. Whenever he could he went to the river, making long canoeing trips on the Ohio, taking long walks in the hills and woods of the valley, painting river scenes and valley landscapes. This is how he wanted to live. Perhaps when I give myself completely to the river, I will be able then to write a true river book, he wrote in completing the journal entry above. But later on the same day he wrote: I know that the aspiration for a higher life will never be satisfied.

Five years later Harlan gave himself completely to the river, and his new life began. He was no longer alone; he had married a remarkable woman named Anna Wonder Eikenhout, a librarian and an accomplished musician. Harlan was forty-three years old, Anna was forty-one. Together, they made their home on the rivers shore for two years, at Brent, Kentucky, a shantyboat community; then for four and a half years they drifted down the Ohio and the Mississippi in the tiny houseboattheir shantyboatthat Harlan had built, living a free-flowing, natural, river way of life.

This is the story told in Harlan's Shantyboat Journal. It begins as Harlan and Anna take their lives to the river. Now in Harlans journal, the I and my have become we and our, and despair has turned to joy and hope: The whole day was morning. Now, when the stars are shining, the stars of winter, and we await the moons rising over the hills directly across the river, there is the same exhilaration and our aspirations seem almost realized. They would be fully realized by the end of Harlan and Anna's drifting river journey. And Harlan would write his true river book.