Payne Hollow

Journal

Payne Hollow

Journal

Harlan Hubbard

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY THE AUTHOR

Don Wallis, EDITOR

Illustration on courtesy of Florence Fowler Burdine;

other woodcuts by Harlan Hubbard are reproduced courtesy

of Claude W. Caddell.

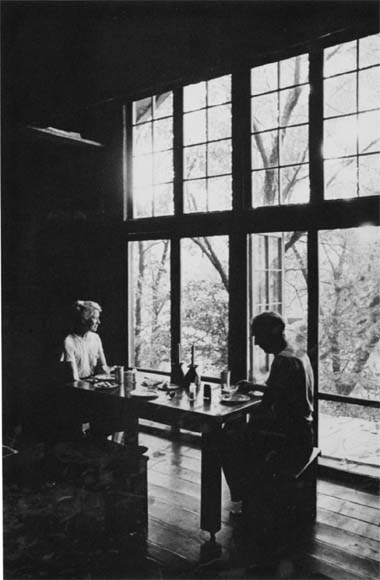

Frontispiece: Harlan and Anna Hubbard at

Payne Hollow. Photo by Bill Strode.

Copyright 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2009

The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from

the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-9325-0 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Contents

Payne Hollow Journal

Editors Preface

Harlan Hubbards Payne Hollow Journal is presented here not in conventional journal formday by day, year by yearbut season by season, to reflect the essential way the Hubbards lived: All our living is regulated by the revolving seasons, Harlan wrote. They determine what we do, what we think and talk about, what we eat, the pattern of each day.

The pattern of each day: the pattern of the seasons: the pattern of a life. Moving through the natural cycle of the seasons, the Hubbards life at Payne Hollow was always changing, yet always the same; Harlans appreciations were constant, and, like the seasons, constantly recurring and renewed, season after season, year after year. This is one of the wonders of life at Payne Hollow, and this presentation of Harlans Journal honors it.

Harlan kept the Journal from 1952 through 1968; the year of each entry is noted in the text. Editing of the entries excludes the customary ellipses denoting deletions. Interested readers may consult the entire unedited journal at the University Archives of the University of Louisville, where many Hubbard materials are collected.

In editing Harlans Payne Hollow Journal, I have sought to reflect the spirit in which he kept it: I am deeply concerned with how each day, each minute is spent, Harlan wrote, and this is a kind of memorial to the passing days.

Don Wallis

Introduction

Payne Hollow Journal is the third and final volume of the journals of Harlan Hubbard, artist, author, and wilderness homesteader whose life (19001988) is an enduring legend along the Ohio River. His journals tell the story of his life. In the first volume, Journals 19291944, Harlan grows into middle age a lonely, restless, often despairing seeker of his lifes purpose and meaning. In the second volume, Shantyboat Journal (19441951), his life is transformed. He is no longer lonelyhe has married a remarkable and gifted woman, Anna Wonder Eikenhoutand he is no longer restless or despairing: on the river he has found his place, and he has found purpose and meaning in his life.

I had no theories to prove. I merely wanted to try living by my own hands, independent as far as possible from a system of division of labor in which the participant loses most of the pleasure of making and growing things for himself. I wanted to grow my own food, catch it in the river, or forage after it. In short, I wanted to do as much as I could for myself, because I had already realized from partial experience the inexpressible joy of so doing.

For seven years the Hubbards made their home on the river, living on the small houseboat (or shantyboat) that Harlan built, at first as members of a shantyboat community near Cincinnati, then, for nearly five years, drifting down the Ohio and the Mississippi and in the bayous of Louisiana. They lived what Harlan called a river way of life. For their food they caught fish in the river, grew gardens on the riverbank, and foraged in the woods; in their boats cookstove and fireplace, they burned the wood Harlan cut and gathered on the shore; and they created together on board their tiny boat a household abundant with fulfilling work, purposeful leisure, art, music, fellowship, and love.

At the end of their long drifting journey, the Hubbards extended their river way of life onto the land. In the summer of 1952 they returned to the Ohio River and settled in a remote, secluded, abandoned placePayne Hollownestled in the hills on the Kentucky shore. Here they built a house and established a homestead, and they lived at Payne Hollow for the rest of their lives, until Annas death, at age 83, in 1986, and Harlans death, at 88, two years later. Payne Hollow Journal is Harlans testament to the place and the life they lived there.

The Hubbards settled at Payne Hollow because, Harlan wrote: We were both led on by a common desire to get down to earth and express ourselves by creating a setting for our life together which would be in harmony with the landscape. They began with the building of their house, a simple cabin the same small size as their houseboat, overlooking the river, peering out from the trees, so firmly planted in the hillside that it seems to have grown there, Harlan wrote. The long roof lines continue the slope with an upward thrust and a window, tall and wide, reflects the blue sky.

In harmony with the landscape, yes; and the Hubbards lived their lives in harmony with the seasons, their lives changing as the seasons changed, and as the landscape changed with the seasons:

Winter is their freest, purest season, when the Payne Hollow landscape is spare and silent, except for the ringing sounds of birds singingand the ringing sound of Harlans axe. In winter Harlan enacts the ceremony of the cutting of wood, venturing out even in the harshest of weather to do his pleasurable work: The day cold and bright, the earth frozen all day.... It is a joy to cut wood on the snowy slopes. In the winter evenings Harlan and Anna sit together by the fireplace and read to each other, or play music together, or quietly perform their household tasks. Winter, Harlan wrote, an enduring time, when change almost comes to a stand.