Authors Note

Some time ago a person asked me how long Ive been an Indian. My answer was since the day I was born.

Out of ignorance and lack of information a lot of people have no idea about who we are as Natives.

We cannot be lumped into one linguistic or cultural group. We have been and still are a collection of Nations in a Nation called Turtle Island.

We werent discovered; we were here long before anyone thought of looking.

European people said that they were created in Europe, but when we say that we were created on Turtle Island, they point out oh no, you crossed the Bering Strait. (Quoted from Dan the Lakota Elder in Neither Wolf Nor Dog by Kent Nerburn.) What right do they have telling us this?

Ever since I was a young boy I had a story in my head waiting to get out. I knew very little about my ancestors. What I did know was that my Great, Great, Great Grandfather Oliver Cota in the 1840s brought his family from the Petite Nations, an Algonquin reserve in Quebec, and built a log cabin in Bedford Township north of Kingston, Ontario. The cabin still stands to this day.

However, what of before before the Europeans stumbled across Turtle Island? Who were we, how did we survive and live in this land?

The story you are about to read is a book of fiction, but it is as historically accurate as possible. It is the story of the Ommiwinini (Algonquin People) in the early 1300s and how they lived.

There is very little written about the Algonquins and artifacts are few and far between. I travelled from Thunder Bay to Newfoundland and points in between to do my research. The Internet proved to be an immense help, but again there is very little information written about my ancestral Nation. What exists is informative and historically important. As difficult as it was to gather information, I gleaned bits and pieces from many sources and interwove it into my story. Museums in Thunder Bay, Midland, Ottawa, Quebec City, and St. Johns, Newfoundland, helped to give me the insight I needed. These museums were able to aid me with small tidbits of information about my people that I was able to use. Again the recurring theme repeated itself, very little information about the Algonquins. In the two years of writing my story, I read twelve books that were able to shed some light on my people, how they lived, warred, and interacted with themselves, their allies, and enemies. None of these books, though, were a definitive story of my people.

My most important acquisition was an Algonquin dictionary for which I am deeply indebted to David Bate of the Ardoch Algonquin First Nation and Allies for finding and relaying this important document. This document is called Algonquin Lexicon by Ernest McGregor for the Kitigan Zibi Education Council.

In the end, my research was a long, drawn-out affair that came together like a jigsaw puzzle.

As you read this novel the two hopes that I have are that you learn something that you didnt know about the Algonquins and their Allies, and that it will help in a small way to bring attention to the Algonquin language.

I want to give special thanks to Max Finklestein for his knowledge of canoeing the Ottawa River watershed. All of my friends at the Colonnade Golf and Country Club, Marie from Queens University, Jim Corrigan, Frank Gommer, and the twins Lauren and Adrie for my character foundations. My new friends at the Glen Lawrence Golf Club for giving me even more future personalities to work with. Larry and Yvonne Porter for believing. My Mohawk golfing buddy and true friend, Ed Maracle. My sisters Vicki Babcock and Cindy Vorstenbosch for their constructive criticisms. My wife Muriel for all her help. My final thanks to my wonderful friend who meticulously edited my book, Janette St Brock.

This book was made possible through a grant from the Canada Arts Council Aboriginal Emerging Writers Program.

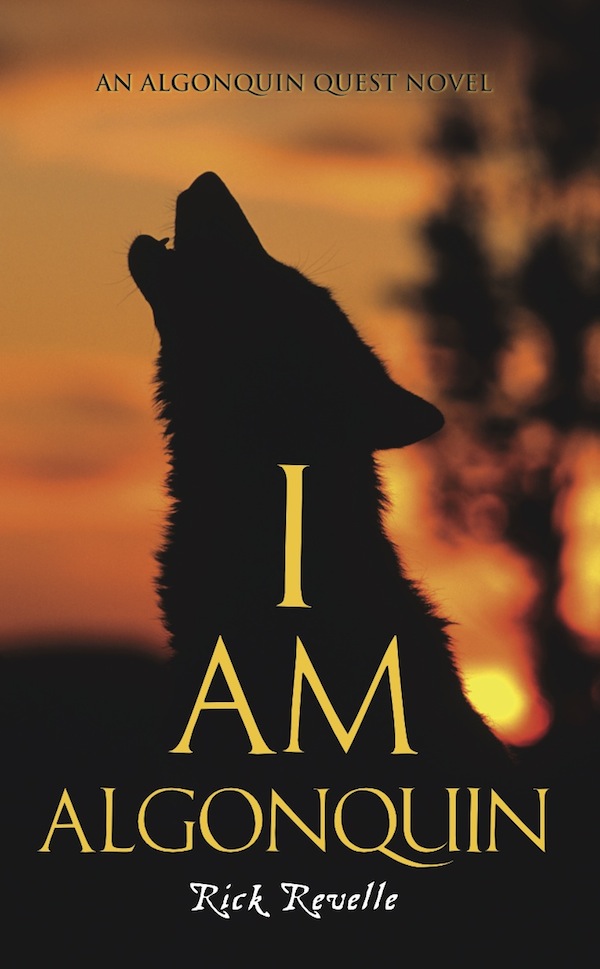

My name is Mahingan, which means wolf in my language, and I am Ommiwinini (Algonquin) from the Kitcispiriniwak tribe (People of the Great River), one of the eight Algonquin tribes of the Ottawa Valley.

I was born right after the warming period that my ancestors had lived through, mild winters, and warm summers. When I was birthed, it was the start of the great cooling period of colder winters and cooler summers.

I was born in the year 1305, and this is my story the story of an Algonquin warrior and a forefather of the Great Chief Tessouat.

1

The Hunt

I WOKE UP WITH the stark realization that I was in unrecognizable surroundings. It took me a few seconds to remember where I was and why I was there. My small hunting party and I were six days into a trip north to find game.

We had built a small cedar enclosure for the evening and this is where I awoke. The shelter was made entirely of cedar boughs and small saplings used to hold the boughs in place. With five warriors, two young boys, and three animosh (dogs), the body heat and small fire kept us very warm. We had built five of these along the way and some would serve us on the return trip for shelter.

The winter was starting out to be one of hunger for the Ommiwinini. Very little snow made the hunting of the mnz (moose) and wwshkeshi (deer) difficult for us. Without deep snow to slow the animals down and tire them out, we were having a gruelling time trying to hunt them with our lances and arrows.

The decision had been made among five family units that we would each provide a hunter to go in the direction of Kaibonokka (God of the North Wind) and the Land of the Nippissing to find game. There the snow would be deeper and the game would not escape us as readily.

In the summer, all the Algonquin family units come together and hunt, fish, collect berries, nuts, and fruit, and live as a large village. This is to provide protection against our enemies, who find it easier in the summer to raid, and it gives us a chance to trade and plan for the future.

In the winter we must split into the smaller family units because many of the animals have gone to sleep in their dens and the ice covers the lakes and streams, making the fish hard to get to. With the smaller family units we ensure that we wont over-hunt an area, whereas a larger village would decimate the game in no time. This winter, though, the snows were late and my people were starting to feel hunger pangs. A scarce diet of adjidam (squirrel) and wbz (rabbit) did not keep the hunger at bay for long. If we had to eat our berries and other reserves without the meat we needed, starvation would not be far behind. After waking we started on our way. It was very cold and the sundogs were warning us of colder weather. We could hear the loud cracking of the trees in the forest as the frost started to do its work.

With my fur hat, heavy mitts, fur robes, and moccasins, I was starting to work up a sweat with our quick pace. However, my face could feel the sharpness of Kaibonokkas breath and I would soon have to put a scarf of adjidam across my face.

My companions were all bundled up like myself, and we carried our lances in our hands, using them for support in the rough terrain. Our bows were slung over our backs with our arrow quivers, as well as our gimag (snowshoes) that we used for the deep snow. Our knives and clubs were tucked into our leather belts.

My two brothers, Kg (Porcupine) and Wgosh (Fox), were with me. Kg was a fierce warrior and had a dent in his head from a Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) war club many years ago. The wound had long since healed, but he still suffered at times from unexplained head pain. My other brother was younger than Kg and me. Wgosh was a good tracker and hunter, but he had yet to be tested in battle.