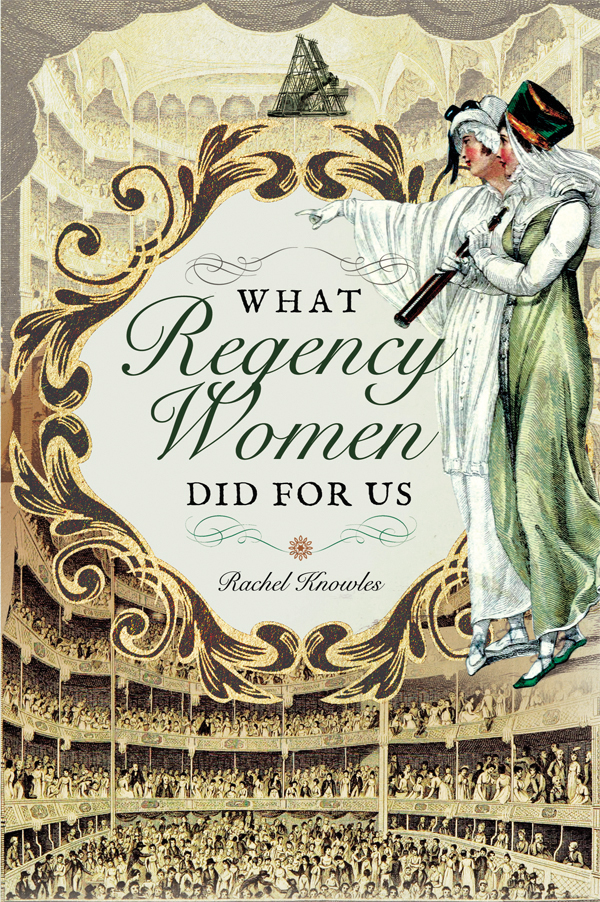

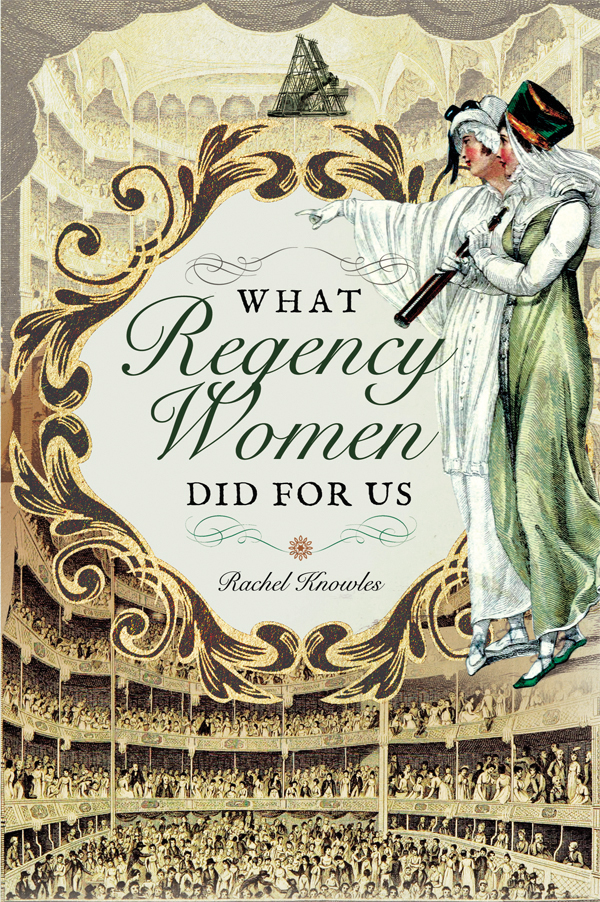

What Regency Women Did For Us

What Regency Women Did For Us

Rachel Knowles

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

PEN & SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley, South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Rachel Knowles, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47388 224 9

eISBN 978 1 47388 226 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 225 6

The right of Rachel Knowles to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

This book would never have been written without the support of my friends and family. I would like to thank them for their encouragement to keep going and for their patience in seeing less of me then they would have liked whilst I have been writing this book. I especially want to thank my husband, Andrew, who has helped me believe I could succeed, and given me invaluable editing advice, as well as providing the photographs.

I would also like to thank Trevor Adams for kindly sharing his research on the Parminters and Elaine Tovell for help with the French translation of the article on the Parminters mountain climb. Thanks also go to Timothy Collinson for his help with indexing, and Karyn Burnham and the team at Pen and Sword Books for helping to get this book ready for publication.

Rachel Knowles

December 2016

Introduction

This book tells the stories of twelve remarkable women who lived during the Regency period. Each of them made an impact on the communities in which they lived and left a legacy for future generations a legacy thats still tangible in the twenty-first century.

When was the Regency?

The Regency was the period of nine years from 1811 to 1820. It was so named because during that time the United Kingdom was ruled by a regent rather than by the king. For many years, George III had been suffering from bouts of an illness that made it seem as though he was going mad. He was probably suffering from the hereditary disorder porphyria. In 1810, his youngest daughter Amelia died and this seems to have triggered the kings final bout of illness from which he never recovered. Parliament judged him unfit to rule and appointed his eldest son, the future George IV, as regent to rule in his stead. When George III died in 1820, George IV became king and the Regency period came to an end.

Although the actual Regency was quite short, the term Regency has come to represent a period of time much wider than the nine years to which it actually relates.

The Regency is seen as a time of glamour and romance, elegance and etiquette. Its tone was set in part by the Prince Regent himself, whose lifestyle was cultured and extravagant, in direct contrast to his fathers rather ascetic ways. He held sumptuous entertainments at his Carlton House palace in London and poured money into his building projects, most notably his lavish, fantastical summer home, Brighton Pavilion.

This Regency feel encompasses the years from about 1780 to 1820 or even 1830. Georgian historians love to argue over the precise dates! The Regency occurred towards the end of the Georgian period.

What was it like to be a woman in the Regency?

For women, the Regency was not always an age of romance. There was no system of equal opportunities and women had very few rights. Their position was far inferior to that of men.

There were huge variations in the amount of education that women received. Some, with forward-thinking parents, were encouraged to learn, educated alongside their brothers or sent away to school. Most received only a basic education, equipping them to operate in the domestic sphere, with the skills needed to run a household and bring up children. Few received the classical education necessary for studying science. And, of course, universities were exclusively for men.

Although allowed to attend lectures at scientific bodies like the Royal Institution, women were debarred from membership. Despite the fact that the Royal Academy of Arts had two female founding members, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser, no other women were admitted to membership until the twentieth century.

Mary Wollstonecraft argued forcefully in favour of the education of women in her A Vindication of the Rights of Woman published in 1792. Many of her female contemporaries shared her views though they did not condone her lifestyle, which stepped outside the moral boundaries of the time. Her opinions were in direct conflict with current thinking which largely believed that womens education should be confined to what they needed for their domestic duties.

A Regency woman who acquired too much learning was in danger of being labelled a bluestocking. Twenty years earlier, the bluestockings were a respected group of intellectuals, both men and women, who met for stimulating conversation rather than to play cards. By the Regency period, the term bluestocking, meaning an intellectual woman, was often applied in a derogatory way, suggesting that too much learning was undesirable and unfeminine.

Marriage in the Regency was by no means an equal partnership. When a woman married, everything she owned became the property of her husband. If she worked, everything she earned was legally his. She had no separate legal identity as a married woman.

A woman had little recourse under the law if her husband treated her badly. Usually her only option was to leave. But a woman had to be desperate to follow this course of action as she had to leave everything behind, including her children, because her husband had all the parental rights. Many women chose to stay with philandering or cruel husbands rather than abandon their children. If they had no friend or family to shelter them, a woman could be destitute away from the marital home.

If a woman was rich, she might choose to stay single. By doing so, she avoided handing over control of her money and, indeed, her entire life to a man who might prove to be unkind. She could also avoid the risk of dying in childbirth a common fate for many Regency women.

However, if she was a gentlewoman without independent means, her options were limited. Remaining unmarried meant she had to rely on her relations to support her, often acting as an unpaid companion in a richer relatives home. Without any such opportunities, she might be forced to become a governess or paid companion, or risk ending up a pauper.

In the lower classes, marriage was still the most usual option for a woman but if she could not, or would not, marry, there were more occupations which she could engage in to support herself, from going on the stage to setting up in trade.

Next page