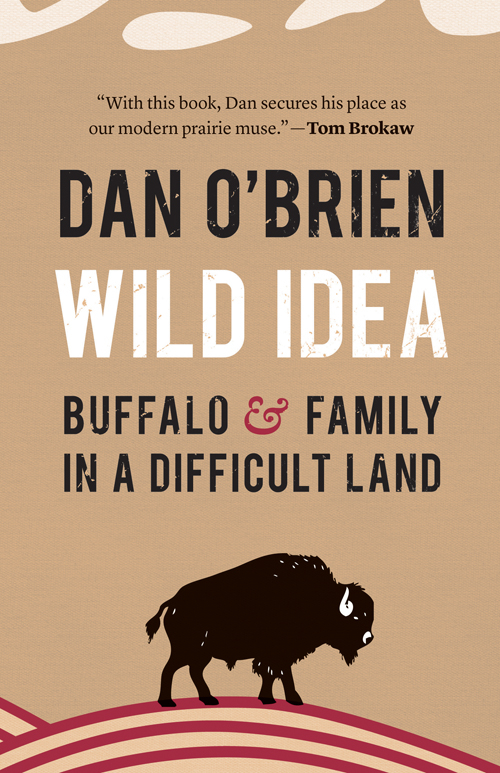

Wild Idea is a lyrical tribute to the idea of buffalo back on the plains, the rewards and challenges of putting them there. But it is so much more. Its about all the life on the prairie, on the hardscrabble ranches and in the small towns. With this book, Dan secures his place as our modern prairie muse.

Tom Brokaw, NBC journalist and author

Dan OBriens book strike me as a gentle but badly needed confrontation.... Figuring out how to realign the way we live with the health of the ecological systems that support us is the single most important challenge of the twenty-first century, and that makes OBriens book an essential meditation.

Edward Norton, actor and UN Goodwill Ambassador for Biodiversity

Making strong, lasting connections between the rugged land and the strong people is a staple of life on the Great Plains. Dan OBriens gift is helping people understand this connection and the basic and difficult truth that sustainable living is not simple; it is as matted and dense as the thick fur that defines the buffalos very nature.

Tom Daschle, former U.S. senator from South Dakota and former U.S. Senate majority leader

Wild Idea

Buffalo and Family in a Difficult Land

Dan OBrien

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2014 by Dan OBrien

All rights reserved

Publication of this volume was assisted by a grant from the Friends of the University of Nebraska Press.

Cover image iStockphoto.com/Big_Ryan

Author photo courtesy of Jill OBrien

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

OBrien, Dan, 1947

Wild idea: buffalo and family in a difficult land / Dan O Brien.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8032-5096-3 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8638-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8637-5 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-8638-2 (pdf).

1. OBrien, Dan, 1947. 2. RanchersSouth DakotaBiography. 3. Bison farmingSouth DakotaBroken Heart Ranch. 4. Ranch lifeSouth DakotaBroken Heart Ranch. I. Title.

SF . A 45 O 273 2014

636'.01092dc23

[B] 2014007956

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Wild Idea

Part 1

Some summer nights, when I step out onto my ranch house porch, I am met by the immense, roiling waves of color from the northern lights. In other seasons I find coiled rattlesnakes or perhaps a wind so cold that skin will freeze in minutes.

By any economic ciphering, choosing the Great Plains for my home has caused me to slip behind my contemporaries who chose New England, or California, or the hills of Georgia. Still, like loving a drunk, I had little choice. For over forty years the prairies have been my home and Ive shared them willingly with all of the species that call them home. It took many years for me to understand that this place is more than a chaotic jumble of species clawing at each other to assert themselves. It is a complex web of life clawing to keep its balance. I love the wind that stokes me as I sit on my front porch, even when it is too cold to endure. It is the wheezing breath of a single, huge, living thing, and I am a part of it.

Between 1972 and 1990 I worked as a biologist, first for the State of South Dakota and then for the Peregrine Fund, based at Cornell Universitys famous Ornithology Laboratory. I had no formal training in biology so my duties were really the work of a technician, always seasonal, and always in the mountains and plains of the Intermountain West. The focus was on helping to reestablish the endangered peregrine falcon to the cliffs along the Rocky Mountain Front, but my mind always wandered to the entire ecosystem that the birds depended uponthe rolling, untold miles of grass that we call the Great Plains.

The falcons were raised from captive parents, first at Ithaca, New York, then at Fort Collins, Colorado, and finally at Boise, Idaho. My colleagues in the labs hatched the chicks and I picked them up at about one month of age. My job was to get the chicks to one of several dozen release sites then do my best to see that they learned to fly and hunt for themselves. It was wonderful work, freewheeling and physically challenging. I traveled by pickup, horseback, helicopter, and on foot to a different site every day. Almost everyone who helped in the effort to reestablish peregrine falcons was young, but it was more than youthful exuberance that kept us going. We were driven by the conviction that we were doing something of real value. As early soldiers in the environmental struggle that is still searching for definition we sensed that our lives were under siege by immense forces beyond our control.

DDT , used aggressively for decades by agribusiness, is a powerful insecticide that increased crop yields around the world. But it was clear to most of us that the benefits were grossly outweighed by the harm. The toxic chemical quickly spread into the entire food chain and did damage to all sorts of species, from soil microbes to human beings. In 1972 DDT was banned from use in the United States. By then it had nearly wiped out many bird species at the top of the food chain where the poison accumulated. The peregrine falcon, a pinnacle species, was decimated by DDT because it fouled up the falcons reproductive system. The first people to notice and respond were a small group of falconers who hunted with and kept peregrines in a quasi-captive state. Those of us with an acute interest quickly became involved. In the end it was a massive effort by thousands of people that brought the peregrine back from the brink of extinction.

The peregrine falcon was placed on the endangered species list in 1970 and it stayed there until several hundred nesting pairs had returned to their old haunts. One day in the fall of 1994 I saw four peregrine falcons in one afternoon on the plains east of Colorado Springs, Colorado. I had never seen peregrines in that area before. I was on my way back to my little ranch on the northern edge of South Dakotas Black Hills after a summer of releasing peregrines. Since April Id been going strong, and because I was anxious to get home, I wasnt even looking for peregrine falcons. But that day they seemed to be everywhere. During my entire life I had sighted only a few wild peregrine falcons and that afternoon I stumbled across four. It was a sign, and by the time I got home I had made up my mind that my work with the peregrine was finished.

When I got back to my ranch, I sat on my front porch and looked southeast toward where Bear Butte rose up from the prairie floor like a sentinel guarding the Black Hills. The butte looked lonely and the sight of it made me wonder what I would do with my life from that day forward. It would be another five years before the wheels of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service worked through the red tape to remove the peregrine falcon from the endangered species list, but it was already clear that the peregrines living on the eastern shoulder of the Rocky Mountains would be with us for at least a few more generations. The immediate crisis had passed.

The sun was going down and putting on a show for anyone who would take the time to watch. The colors in the autumn grasses pulsed with the breeze and the individual blades cast shadows on each other. As the grasses waved, the colors moved from gold to red, and I thought about all the life that depended on that mosaic. I thought about the mammals, from rodents to deer and antelope. I turned my best ear to the breeze and imagined that I could hear the movement of the billions of insects that supplied the baseline protein for the ground nesting birds for which the prairies are famous. The falcons were again preying on those birds and, at least for awhile, all those wheels would continue to turn.

Next page