September 1835

Albemarle Island, Galapagos

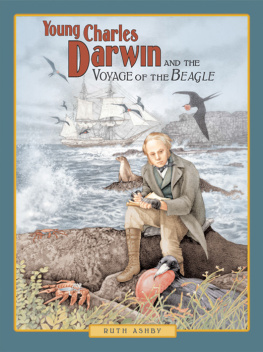

Mr. Darwin crouched in front of a giant tortoise, notebook in hand. His homemade magnifying eyeglass, which the sailors of the Beagle all made fun of, gave him the look of a studious buccaneer.

See how the shell is completely domed, Covington, he said. It means they cant raise their necks at all.

Reckon they dont need to, sir, I said, watching the tortoises chewing. Theres a lot of grass growing here, so theyre always looking down at the ground anyhow.

Mr. Darwins eyebrows shot up and he grinned. An interesting observation. Could the shell design force this behavior, or could it be the other way around?

I didnt know the answer to that but felt my cheeks warm in the glow of his approval. When our voyage began four years ago, I was ships fiddler and cabin boy, but for the last two and a half years Id been assisting Mr. Darwin, making use of my letters, like my da would have wanted. I liked to think Id picked up some of his way of thinking too.

I wonder if it would be difficult to ride on such a shell, I said idly, then kicked myself. That wasnt the kind of thing Mr. Darwin wanted to hear from his assistant!

Well, ready yourself, then, said Mr. Darwin, and to my surprise he clambered aboard one of the giant tortoises, perching on top of its shell. What are you waiting for?

The ancient animal stretched out its long crusty neck and hissed at the unexpected weight, then took a ponderous step. Mr. Darwin just managed to catch his balance. His laugh rang out, much clearer and louder than his voice, and he slapped his thigh.

This was more like it. The master might be awful clever and mostly serious, but he was only a young man himself, and I loved those rare moments he was game for a laugh. Wed been measuring tortoise shells all day and a break was more than welcome.

I eyed up the tortoises and chose a smaller one that seemed to be fast asleep, its head tucked into its wrinkled neck like an acorn in its cap. I scrambled onto its back. It wasnt as easy as Mr. Darwin made it look. My master was tall and sometimes stooped. He had a way of swinging his arms when he walked but wasnt nearly as clumsy as he looked. My knees slipped on the mottled shell, but I finally managed to settle my behind in the center. When the tortoise started to move, I felt as though I was back on the Beagle sailing around the stormy waters of Cape Horn.

Mr. Darwins tortoise was heading across the lava field, but mine stopped and dipped to munch some grass, nearly tipping me off.

Youve chosen a donkey, Covington, but mine is a noble steed! called Mr. Darwin.

I laughed out loud as he waved his hat in the air. If only Da could see me now.

A shadow darted over me and I looked up. Two magnificent frigate birds swooped on the air currents, massive black wings almost as sharply pointed as their beaks and tails. Their red throats flashed.

Mr. Darwin stared upward too. Looks like some weather coming in, Covington

I could see it too. The sky was suddenly the color of a bruise and the air smelled of copper pennies.

The young sir hopped down from the tortoise. Did you pack the specimens well? His voice was serious once more.

I did, sir, I replied, and slithered down myself. My tortoise had tucked its head back in. I pulled up some grass, which it took from my offered hand with a beaky, toothless mouth. I liked the tortoises; there seemed to be a lot of thinking going on behind those old black eyes.

Make haste, then, boy. Lets get them back to the barrels, said Mr. Darwin.

The casks of wine would preserve the specimens wed collected until we landed at a port where they would be sent all the way back to Mr. Darwins colleagues in Cambridge.

A fat spot of rain hit my arm and a gust of wind nearly separated me from my hat. The weather changed rapidly in this part of the worldwe always had to be ready for it, and Mr. Darwins blue-gray eyes looked dark beneath his frown. I shouldered our knapsacks and stowed the logbook in my satchel. Mr. Darwins eyeglass had been discarded on a boulder, and I slipped it inside my fiddle case, then thumbed some wax around the seals to keep out the water. Id brought my fiddle as an experiment to see the effect of music on wildlife, but thered been no time to play in the end. Mr. Darwin wasnt partial to the old instrument; he called it Scratch and the name stuck.

The spatters of warm rain turned into a downpour, and we hurried across the black lava plain toward the shore where the rowboat waited.

Watch your step here, Syms, said Mr. Darwin, and I nodded. Beneath the lava plain were tunnels, which had once been underground rivers of molten lava, and there were dangerous holes near the surface.

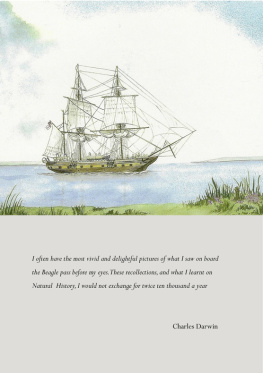

Mr. Darwin said these islands looked like the infernal regionswhich to the likes of you and me means hell. The five volcanoes of Albemarle lined up behind us, and ahead, purple-gray clouds the shape of cauliflower had piled behind the silhouette of the Beagle, which was anchored out at sea.

One of the sailors, Robbins, met us at the shore in a bit of a lather, which wasnt like him at all. Youve seen the storm, then, sir?

Mr. Darwin nodded. Lets get back to the ship. All haste.

Robbins took Mr. Darwins equipment and made giant strides through the bright green seaweed that covered the black rocks. We tramped straight into the sea, wading out to the rowboat, which was held steady in the surf by the other seaman, Tanner. I helped my master in first, then scrambled in myself. It had been minutes since our tortoise ride, but the Beagle was now near invisible through the rain, and the sea was dark and spiked. Robbins pushed off from the shore and waded through the surf, then leaped in behind us.