Contents

Guide

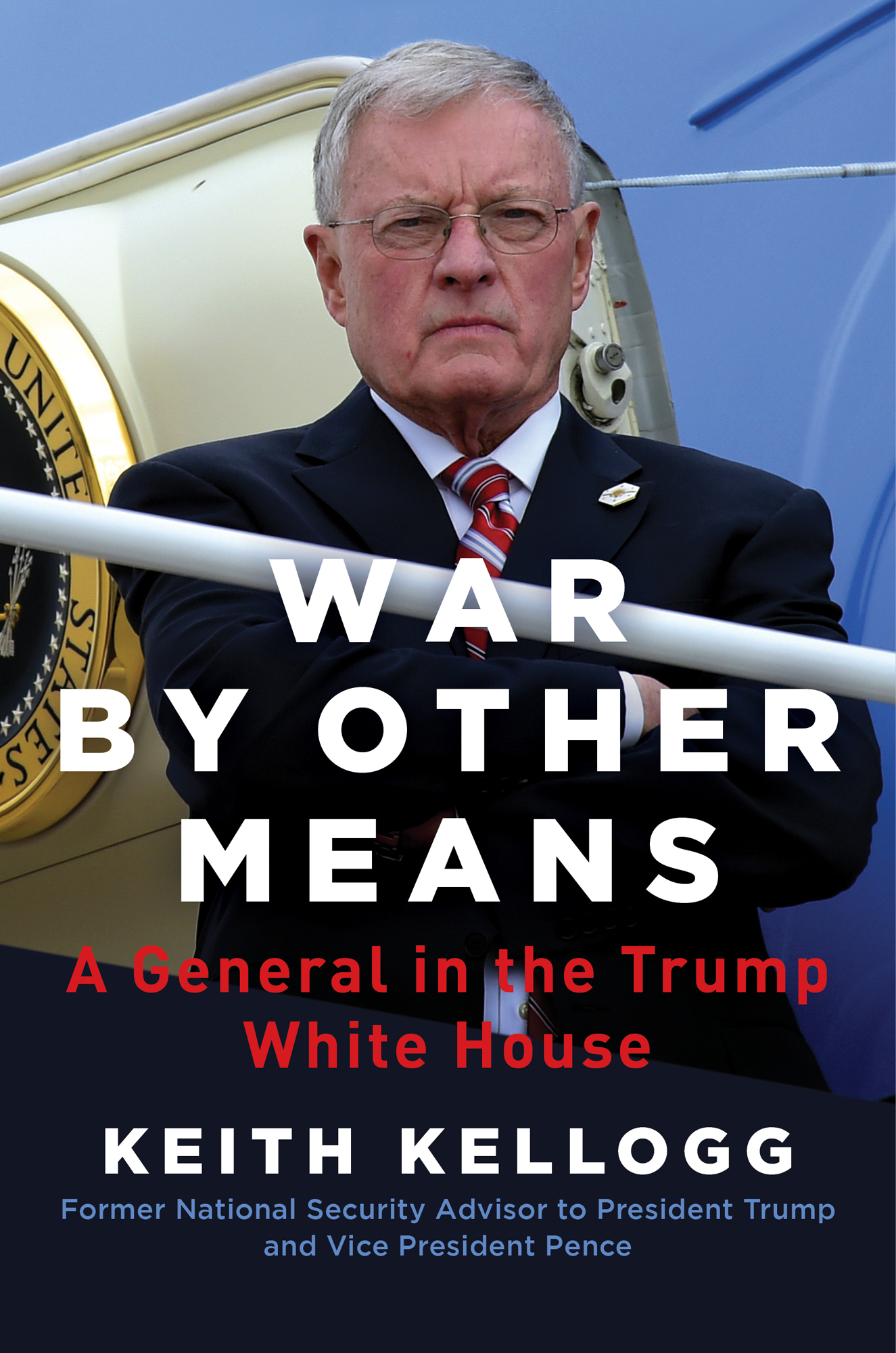

War by Other Means

A General in the Trump White House

Keith Kellogg

Former National Security Advisor to President Trump and Vice President Pence

Success is not final.

Failure is not fatal.

It is the courage to continue that counts.

Winston Churchill

Preface

I t was 7 February 2019. We had just finished the presidential daily briefing session in the Oval Office with the director of National Intelligence. The sensitive and highly classified topics covered in these briefings included information available to only the most senior decision makers.

The president asked me how things were going, and I stayed behind while the others (including the vice president, the White House chief of staff, the director of National Intelligence, and the director of the Central Intelligence Agency) walked out. The only other person remaining in the room was Pat Cipollone, the White House chief counsel. I told the president I was living the dream.

He smiled and said, You realize youve been with me three years: from the New Hampshire primary to two years here in the White House. Youve seen it all. You should write a book.

I laughed and replied, I dont do books, and walked out.

But the presidents comment that day gave me pause. There had already been many books written about President Trump, but they never seemed to portray the man I knew: a patriotic man with uncanny political instincts, unfailingly loyal to those he felt were loyal to America first.

Donald J. Trump is a fighter. Maybe it would be more accurate to say he is an unashamed brawler when it comes to defending America and Americans. As a soldier, I never found his blunt, belligerent patriotism offensive, as some did. I am proud to have been part of his team and to have worked for his agenda. I am honored to know his family. I am confident that he and his policies will be vindicated by the judgment of history.

During my four years of White House service, I had the privilege of flying on Air Force One and Air Force Two, Marine One and Marine Two; going to Camp David; meeting with numerous heads of state; and even having a private audience with the pope. I visited every continent, save Antarctica, and every war zone involving American troops in the Middle East. I participated in every major national security decision made during the Trump administration, covering issues from the war in Afghanistan to our response to COVID-19.

I spent 1,461 days in the Trump White House. No one in the national security apparatus, as they call it, was there longer. Driving out of the White House complex on 20 January 2021, I asked myself the question every good soldier does after a hard fight: Was it worth it?

This book is my answer.

PART ONE A SOLDIERS LIFE

CHAPTER ONE The Education of a Soldier

I grew up in Long Beach, California, part of an upper-middle-class family. My father was an executive in a family-owned oil-drilling business, and my mom was an active member of the local community. My mom was kind and compassionate, but also energetic, direct, forthright, and a fierce competitor, as anyone who played bridge with her would soon discover.

My dad was the only college graduate on his side of the family, so he ran the business operations for K.L. Kellogg and Sons Drilling, his familys oil-drilling business. It was a stressful job, and part of my belief in America First economics comes from watching, as a teenager, Canadian drilling companies outbid American oilmen for lucrative California offshore drilling contracts.

Like our mother, we Kellogg siblings were all very competitive. My older brother Mike graduated from the University of Santa Clara and played professional football for the Denver Broncos. Later, he went to law school and became a superior court judge in California. My sister Kathie was an off-Broadway stage actress and lived in the famous Rehearsal Club in New York City. She eventually earned a PhD in psychology. My younger brother Jeff went to the University of Oregon on a football scholarship and later became a councilman and vice mayor for the city of Long Beach, California.

I attended Long Beach Polytechnic High School, a sports powerhouse, where I played football and ran track. I was the only white sprinter on our league-winning mile relay track team, and our varsity football team was one-third white and two-thirds minority, but it never occurred to me that this was unusual (this was in the early 1960s). We played in fully integrated sports leagues, and we all just assumed sports was a giant meritocracy: the best players, the fastest runners, started.

Politics seeped into family discussions when John F. Kennedy ran for president against Richard Nixon in 1960. One day, riding the bus home from school, someone passed me a leaflet stating that if you voted for Kennedy, a Catholic, you were voting for the pope. As part of a Catholic-Protestant family, I thought this would make for a lively Kellogg family dinner discussion, and it did, because our family dinner discussions needed little excuse to become verbal bar fights.

My goal in high school was to receive a congressional nomination to West Point, and that required a series of competitive exams in English and mathematics that would help guide our congressman, Craig Hosmer, in his choice. I took the exams thinking they were something of a formality. My dad had been a campaign manager for the Republican congressman (and navy veteran and Long Beach Polytechnic alumnus) in the days of true retail politics. In the end, my English scores were very good, my math scores were very average, and the nomination was not mine. I became the first alternate, and the primary selection went to a high school classmate, Richard Doty, which turned out to be a good thing for both of us. Richard graduated from West Point, became an Army doctor, and retired as a colonel.

I needed a new path into the military and picked the University of Santa Clara, which at the time was a small conservative Jesuit school with a solid Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program. There were family connections there too: my older brother was there; and the dean of the political science department, Dr. Barney Kronick, was a family friend, having attended the University of California with my mom, dad, and aunt.

I majored in political science while taking many American history classes. I also played football and learned that not everyone felt the way my family did about race. When we arrived at the beautiful northern California campus, Pat Malley, the head football coach, pulled my parents aside and asked if they minded my being assigned a black roommate, namely, fellow freshman Bobby Miranda. My parents were shocked. The answer was, Of course not. My mother was insulted that he had asked.

Bobby was a high school All-American running back from Encinal High School in Alameda, California. We instantly became great friendsand remain so todaybut he was so well liked that he became the most sought-after roommate in the school, and the administration decided to move him around. I never got to room with him again after our freshman year.

Playing football and pursuing other academic interests pushed me from a spring to a winter graduation date, which turned out to be fortunate. I didnt graduate at the same time as most West Pointers, and I was a designated Distinguished Military Graduate, so I figured I had a better chance of getting a military assignment I wanted. What I wanted was the infantry, and I was stunned when I was informed that I had been assigned as an air defense artillery officer. I walked into the office of our professor of military science, U.S. Army colonel Robert OBrien, told him of my assignment, and asked how I could transfer to the United States Marine Corps. OBrien, a World War II glider troops veteran, got the message, and I was soon commissioned as an infantry officer.