All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968 ), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may beliable in law accordingly.

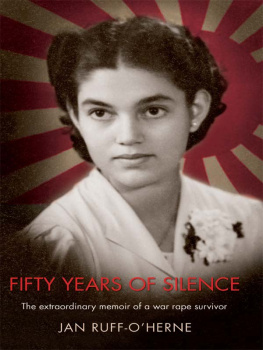

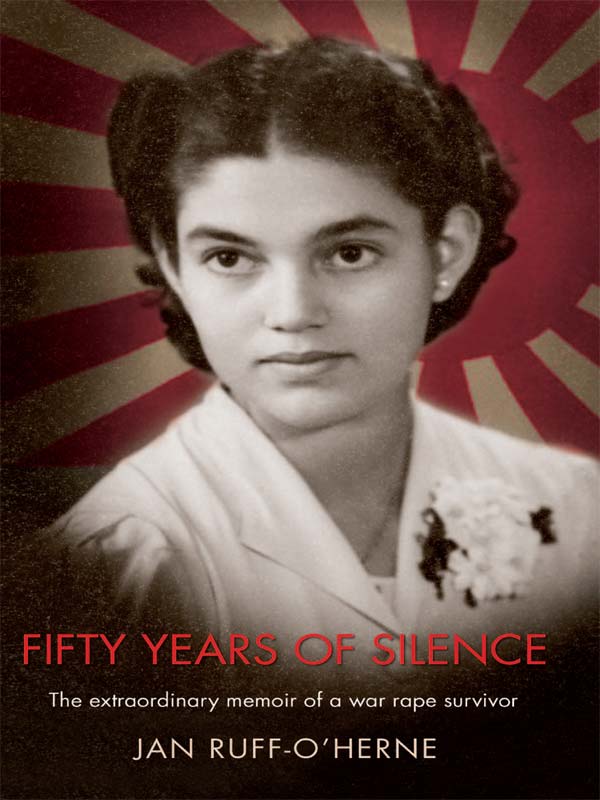

Fifty Years of Silence

9781742754260

A William Heinemann book

Published by Random House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100 Pacific Highway, North Sydney NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First published by Editions Tom Thompson/HarperCollins Publishers, 1994

Second edition published by ETT Imprint, 1997

This revised and updated edition published by William Heinemann, 2008

Text and illustrations copyright Jan Ruff-OHerne 2008

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of Random House Australia.

Addresses for companies within the Random House Group can be found at

www.randomhouse.com.au/offices.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Ruff-OHerne, Jan.

Fifty years of silence.

ISBN 978 1 74166 746 2 (pbk.)

Ruff-OHerne, Jan.

Comfort women Indonesia.

World War, 19391945 Prisoners and prisons, Japanese.

World War, 19391945 Personal narratives, Dutch.

World War, 19391945 Atrocities.

Indonesia History Japanese occupation, 19421945.

940.540509598

Prison camp sketches by Jan Ruff-OHerne

This book is dedicated to my late husband,

Tom Ruff, with all my love

Contents

Authors Note

Indonesian words and place names in this book have not been modernised; they are the preWorld War II spellings.

In a few instances I have also chosen to use words and expressions no longer widely used (such as Japs for the Japanese), because these were the words we used every day in the prison camp, and they convey my feelings and emotions at that particular time and place more accurately than any modern equivalent could ever do.

When I was a young girl living at home with my mother and father I always had the feeling that there was something very special about my mother, but I had no idea what it was.

She had a dignified, extraordinary aura about her.

She was unique and strong, and people were drawn to her.

How ironic it was to think she could not bring herself to tell us of her painful story, when all the time my sister and I were so proud of her.

Ward, myself and Aline.

Part I

An Idyllic Childhood

O MA, PLEASE TELL ME A STORY from when you were growing up in Java?

My little granddaughter Ruby was looking through my old photograph album. Her smiling face looked up at me with expectation.

Which story do you want to hear this time? I asked.

She turned the pages of the album carefully, almost with reverence, each picture a different story.

Tell me about the house, Oma, and about the little lizards climbing up the walls. Tell me about all the animals you had and the snake you caught, and when you fell out of the banyan tree. Tell me about your French grandpa and how you always had to sit with a straight back at the table and what about when you went climbing the mountain and your legs got covered with black leeches. Tell me, tell me, Oma!

I looked at her eager young face and felt the urgency of passing on my story: the roots, the family traditions, the richness of the past. It was all there, buried among the pages of this family album.

There were some photographs which were absent, though photographs which had never been taken. The images were deeply and permanently engraved on my mind and locked away in my heart, but the stories they told were too shameful, too horrific to tell. I had kept them secret from my daughters, my grandchildren, from family and friends. The need to tell these darker stories was growing just as strong, just as powerful.

My granddaughter had heard the beginning of the story, and the many small moments that made it up, so many times before. Like all children she loved repetition and the security of knowing what was coming next. I looked at the photos, some of them faded with age. Each picture held a treasured memory of a beautiful childhood spent in Java in the Dutch East Indies, now called Indonesia.

I could feel again the heat and the humidity. I could hear the sounds of the distant gamelan music, mixed with the song of the cicadas and the crickets, filling the night with a tropical symphony. Smoke drifted up from the mosquito coils burning as we sat on the front verandah of our house watching the toads jump up and down after the many insects. But most of all I remembered the smells charcoal fires, tropical fruits, fragrant flowers, the unmistakable smell of the sate vendor.

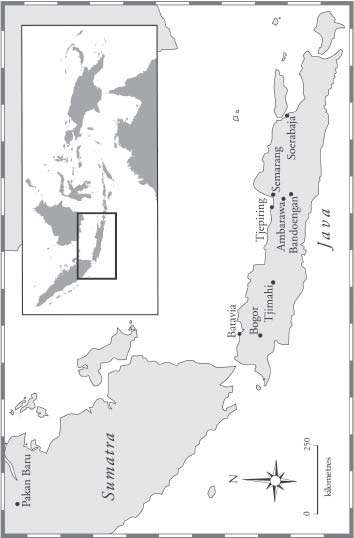

I was born in Java in 1923, the fourth generation of a Dutch colonial family. Ours was a happy family and I had the most wonderful childhood anyone could imagine. I was the third of five children, growing up on a sugar-factory plantation, called s.f. Tjepiring, near Semarang in central Java. (The s.f. stood for suiker fabriek , or sugar factory.)

My parents were loving, intelligent and artistic, both very talented in their own different way. I owe them so much; I am only what I am now because of them. They brought me up in the true Catholic tradition, sending me to Catholic schools and college. My parents, especially my father, implanted in me a great and strong faith and a love of prayer and Holy Scripture, and the Mass. The Mass was very special to us. Because we lived so far away from the city of Semarang, we could only attend once a month when a Dutch priest, Father Beekman, would come to Tjepiring and offer Mass for the Catholics in the district.

Father Beekman would stay at our house, and in the evening we would discuss Holy Scripture and theology over cold drinks and soft, classical music from the gramophone. I had an intense and deep faith even from an early age. My faith was my most precious gift from God; it was my support and my strength in the suffering that lay far in the future.

My mother and father were both musically gifted, with a great love of classical music. I have vivid memories of going to sleep at night listening to my parents making music together. My father was an excellent violinist. My mother was an equally talented pianist and singer. She would sing in several languages but she had a preference for German lieder , which she rendered most beautifully in her rich mezzosoprano voice.