I have kept a journal for much of my life. But I have never written a book before and I could not have written this one without the help of colleagues especially Rupert Mackenzie-Hill and Francis Showering; the dedicated work of two lawyer friends who were of immense help in compiling this; and the insight of my family my father John, my mother Shirley, my sisters Syra and Caroline for their love and support, and especially Carolines husband Peter Bayley for his help.

The past years have not been an easy time for my family. To see their name besmirched in print has been harmful to them and caused pain and heartache. My family has been a tower of strength in the face of this and nobody has been stronger or more loyal or more supportive than my mother. I owe her more than I can say. As a poet once said:

Life is mostly froth and bubble,

Two things stand like stone.

Kindness in another's trouble,

Courage in your own.

J ames Hewitts story is, amongst other things, one of contrasts. A fairly consistent description by those who knew him during any part of his fifteen years in the Army is of a capable, charismatic leader, respected and universally liked. In addition, many talk of Jamess huge sense of loyalty and duty to all things army, as well as to his friends, his family, his country and, in this case, to a very particular person.

Ive known James before, during and after the much-publicised affair. Ive seen a man at the top of his career picked amongst fellow officers to lead what was to be the only unit from our regiment to see front-line action during the Gulf Conflict. I was with him during that conflict when he was nicknamed Ice Man for the extraordinary coolness and quiet, capable manner with which he led us into Iraq to take part in over 60 separate contacts with the then enemy, for which he was Mentioned in Despatches for his courage in action.

I spent time with James over 15 years: on holiday, socialising and pursuing sporting interests, unaware of an affair that was a secret as tightly guarded as the Crown Jewels themselves kept from nearly everyone for almost five years.

During the storm of publicity surrounding the release of Anna Pasternaks Princess in Love, I, like many others, wondered what on earth had led James to become involved in this book and it certainly appeared from a distance that there must be some involvement. Why would he go public about something he had manged to keep such a secret for so long? If he was involved, how and why? Whilst I have never found it my place to ask as a friend, I have found the answers in this book.

And the price of this alleged involvement? Ive watched Jamess ranking as public enemy rise to the number one slot right up there with Saddam himself. Ive watched his life being destroyed by the effects of bad publicity, by the back-turning of people who believed what they read in the papers the public, some friends and a few influential senior officers in his regiment, a regiment to which he was and still is devoted. I know a little about the isolation and of the level of despair to which James sank and the effect this had on his family. Ive read the hate mail and Ive watched the newspapers manipulate the facts and ruthlessly hound a sensitive, courageous and honourable man like the pack of cackling hyenas they can at times be.

And the resulting book? Not what I expected. Hardly a gripe or complaint. But a charming book, reserved at times, humorous and passionate at others a good deal about Diana, a person with whom James was evidently captivated. And his delightful observations are not the normal royal watchers combination of second or third-hand research combined with hypothesis, guesswork or plain fiction. Its the real thing and all the more interesting.

Im with James on his decision to publish this book. Not everyone will be. But I see this as an ultimate triumph of good over evil. If you read between the lines, I hope you will see evidence of the goodness in the man and the inherent evil of the gutter press. A press that thrives on sensationalism for its own commercial ends and that seems capable of talking about people only as either extremely nice, or as extremely nasty. And if you talk to any of the many people who know James well, you will find they will side with the decent guy description.

Captain Rupert Mackenzie-Hill,

The Life Guards

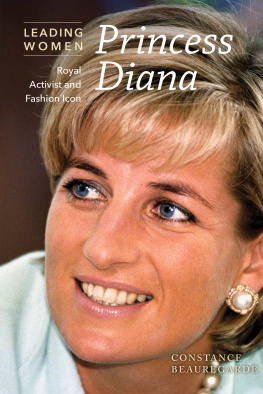

L ast night, I burned some of the most intimate letters written to me by Princess Diana. Believe me, it was not a decision I took lightly after all, these letters are amongst the few keepsakes I have left of the woman with whom I shared a passionate love, and who I love still. They are deeply personal reminders of the past but sometimes ones ties to the past must be severed in order to move on.

I have spent many long hours over the last few months deliberating as to whether destroying these letters would be the right thing to do. My years in the army have meant that I rarely make ill-informed or rash decisions and try to consider all the possible consequences of my actions. Recent events had brought the letters into the foreground yet again and forced me to think about the pain they had caused since Dianas death. They had been taken from my house without my knowledge and sold to a newspaper; I had been forced to go to court to fight to get them back in my possession and they had been an almost constant source of speculation in the press. Their mere existence seems to be an unexploded powder keg and it can surely only be a matter of time before someone sets it alight.

The few letters I chose to destroy were so personal that, if their contents were ever to be revealed, they could surely only ever cause pain. Dianas sons, William and Harry, who have been through so much already, would surely suffer if these intimate missives were ever to fall into the wrong hands or made public. It is scarcely the kind of history that Prince Charles or indeed any other member of the Royal Family would want dredged up yet again.

Why only destroy a few of the letters? Why not burn the lot? Firstly, there were only a few whose intimate content really concerned me and that I feel would cause damage if revealed. Secondly, to be restrained in my actions made me feel that at least I had some control over the situation that I was not being totally motivated by the fear of what third parties might do with the information in the letters or how I might be judged. After all, the motivation for getting rid of them had not been a simple desire to rid myself of my past but, rather, it had been to do the right thing. For a long time it had seemed that everyone other than me was using the letters in some negative way and preventing me from moving forward.

I cant deny that burning the letters was a terribly sad and poignant moment in my life. I am an extremely pragmatic person but I am not without feelings. As I held the pieces of paper in my hands I thought of the happiness I had shared with Diana. I thought about what she might have said had I asked her opinion on what I should do, and felt sure that she would agree with me that to destroy them was preferable to them falling into the wrong hands. She would have wanted me to protect the sons she adored from that kind of attention.

So with a heavy heart but strong conviction, those few letters disappeared forever. My memories, though, can never be destroyed they are safe and I can revisit them should I want to, but for now I have freed myself from an anchor to the past and have taken another step forward into my future.

T his is not an autobiography in the conventional sense, it is an account of certain aspects of my life, some of which has already received a great deal of publicity.