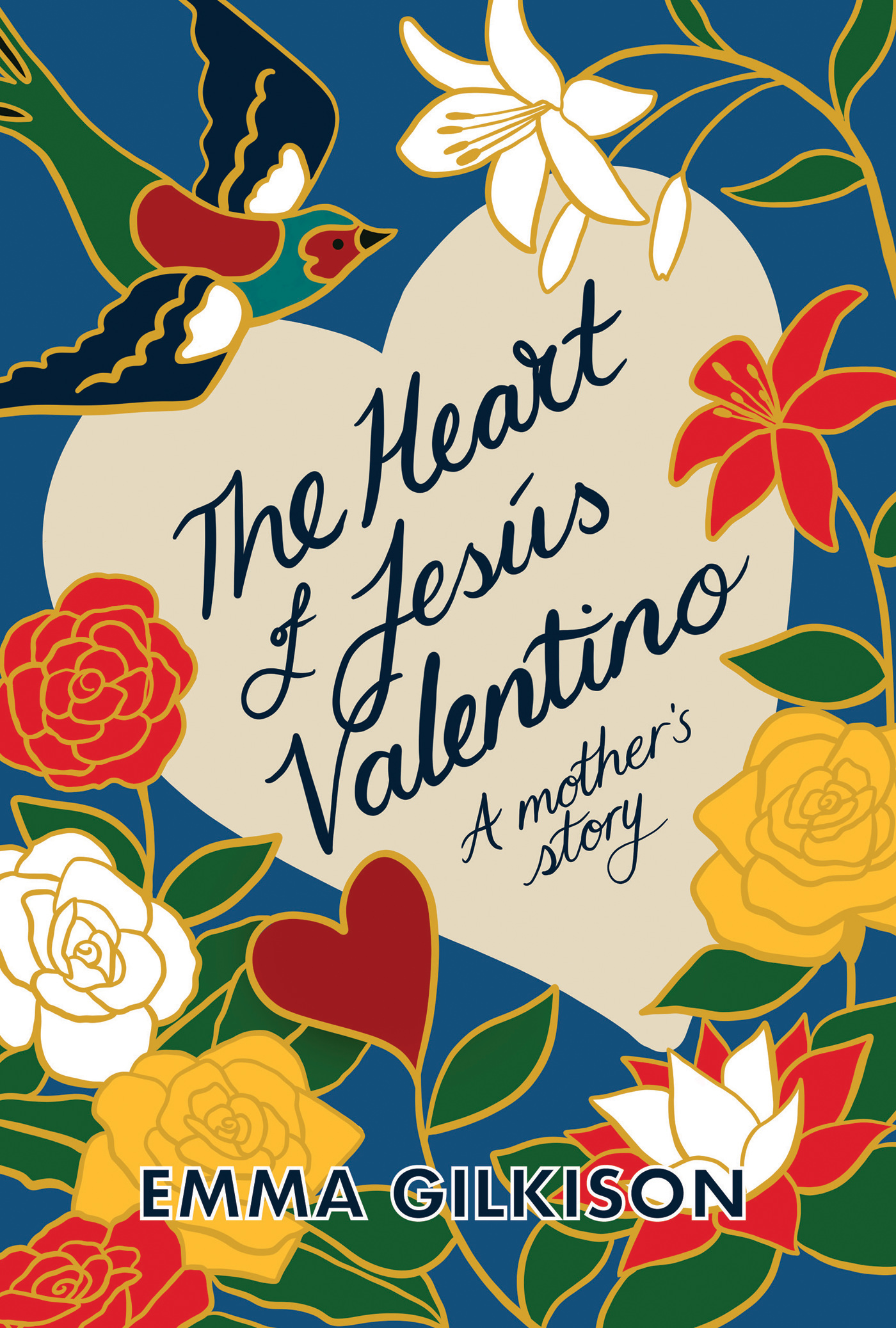

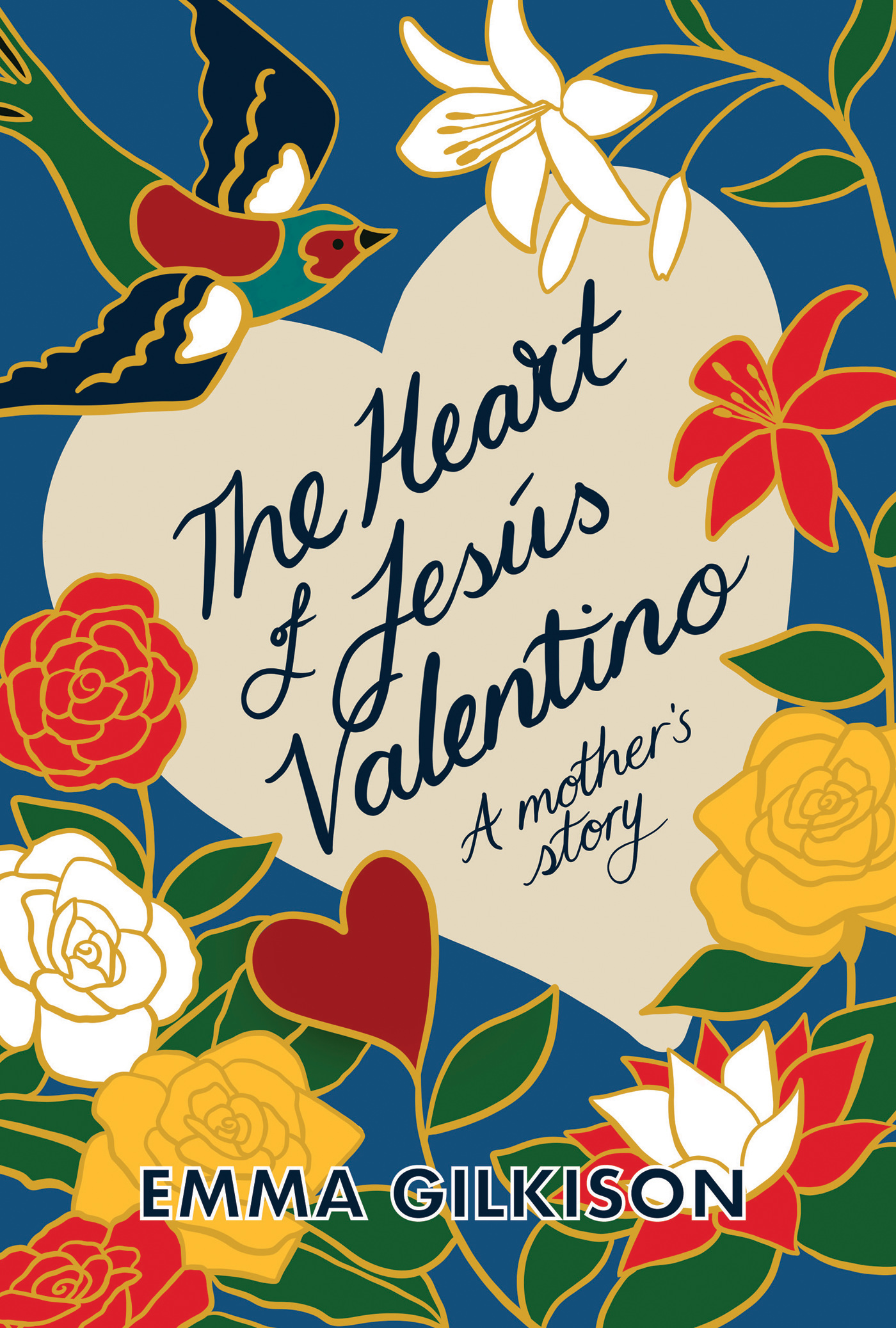

First edition published in 2018 by Awa Press,

Level 3, 27 Dixon Street, Wellington 6011, New Zealand.

ISBN 978-1-927249-58-1

Ebook formats

EPUB 978-1-927249-59-8

mobi 978-1-927249-60-4

Copyright Emma Gilkison 2018

The right of Emma Gilkison to be identified as the author of this work in terms of Section 96 of the Copyright Act 1994 is hereby asserted.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

The author and publisher thank the following for permissions:

The CS Lewis Company Ltd for the quotation on page 187 from A Grief Observed by CS Lewis copyright CS Lewis Pte Ltd 1961

Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill for the quotation on page 74 from The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elizabeth Tova Bailey

The names and personal details of some medical personnel in this book have been changed at their request.

Cover design by Holly Dunn

Typesetting by Tina Delceg

Editing by Mary Varnham

This book is typeset in Adobe Garamond

Printed by Everbest Printing Investment Limited, China

Produced with the assistance of

Awa Press is an independent, wholly New Zealand-owned company.

Find more of our award-winning and notable books at awapress.com.

Ebook conversion 2019 by meBooks.

EMMA GILKISON graduated in Journalism from Massey University and worked freelance and as a columnist for The Sunday Star-Times and The Dominion. In 2013 she gained a Bachelor of Applied Arts (Creative Writing) from Whitireia New Zealand. She has studied short fiction and science writing at Victoria Universitys International Institute of Modern Letters, and her work has appeared in newspapers and magazines. She lives in Brisbane with her partner Roy Costilla and their son Amaru.

All sorrows can be borne if you put them into a story

or tell a story about them.

Karen Blixen

For Jess Valentino

Thank you for helping us bear witness

to all that is beautiful.

Contents

May 2014, Paekkriki

Dear baby, I am writing to you in front of the ocean. The sun is low but warm on my face and Kpiti Island is a giant blue cut-out on the horizon. This is what I want to ask you: Would you like me to keep you in my belly until youre born, or would you like me to stop the pregnancy and for us to say farewell now?

Six months earlier I could never have imagined writing this letter. I was trying to conceive. Whenever my period arrived it was like a sad monthly Sorry, better luck next time message. There had been times when Id thought I was pregnant. My breasts had swelled like water balloons and I was unaccountably tired. I had developed an extraordinary appetite for carrot cake, and hamburgers with beetroot and blue cheese. I was moody and went to pieces after my partner Roy failed to text to tell me hed be home late for dinner.

There were also times when it seemed so auspicious to conceive I felt sure it would happen. There was the trip Roy and I took over the Peruvian Andes to the Valle Sagrado de los Incas the Sacred Valley of the Incas Roys parents birthplace. At the pilgrimage site of a local saint we were doused with holy water and our union blessed by a white-robed priest. I mused that if our child were to be conceived in Peru and born in New Zealand, this would be a perfect reflection of his or her dual nationality.

Then there was the unplanned trip after my grandmothers funeral, when our plane was diverted to Christchurch after gale-force winds prevented it landing in Wellington. What seemed at first a major inconvenience turned into an all-expenses-paid romantic overnight stay in a four-star hotel. According to the Fertility Friend Ovulation app on my phone, I was in the middle of my monthly cycles fertile window.

Whenever my periods due date approached, the wait would be agonising. Id make frequent trips to the bathroom, hoping for the best. But the stories Id told myself about our babys conception remained just that. After a year of trying to conceive, I was feeling worried.

For most of my life until this point my aim had been to avoid pregnancy. One day in the hazy future I might meet Mr Right and wed have a family, but before then I wanted to find meaningful work, live in France, write a book, start doing yoga every morning, learn to dance salsa, and fulfil a dozen other big and little dreams. Before I knew it, I was thirty-four and single. My mother dropped hints that if I wanted kids Id better get a move on. Strangers occasionally asked me if I had children: I must have begun to look as though I might be a mother. But no, Id managed to get the crows feet around my eyes and the bosom heading south all on my own.

By the time I met Roy, motherhood was well on my radar. Luckily, fatherhood was on his too. We were only a couple of months into our relationship when we stopped using contraception. When I wasnt pregnant after six months I decided to have some tests. By then I was thirty-five, that golden number after which a womans fertility begins to nosedive, according to a booklet Id picked up in my doctors waiting room. A scan and hormone blood test showed up nothing unusual. We were told to keep trying for a year. If we still hadnt conceived wed be eligible for a publicly funded referral to a fertility clinic.

When the year ended and there was still no baby, I was willing to take the next step. In my younger days Id thought of fertility treatments as vaguely desperate, the resort of stressed-out executive couples past their baby-making prime trying to force the hand of nature. Now that we were a couple facing infertility things looked rather different.

I decided that after my next period Id book an appointment with my doctor. It was February, a good time of the year to embark on fertility treatment. Roy and I had spent our summer holiday on the west coast of the South Island, tramping through green forests and drinking in sunsets. We felt rested and in good spirits.

When I realised my period was a few days late, I was lolling about at home, half-heartedly doing research for a newspaper blog. I wondered idly if I should make the ten-minute walk to the pharmacy and pay ten dollars for a pregnancy test and decided I would. Itd probably confirm I wasnt pregnant: Id been through this rigmarole several times before.

Back home, I collected a urine sample and dipped the stick in the small plastic pot. Almost immediately I thought I saw a positive pink line. Was it a trick of the eye? Too nervous to watch for the several minutes it takes to get a clear result, I left the bathroom. When I came back, there was no mistaking it: the test was positive. I held it before my eyes and walked around the house in circles. Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god. I was truly knocked for six.

Next page