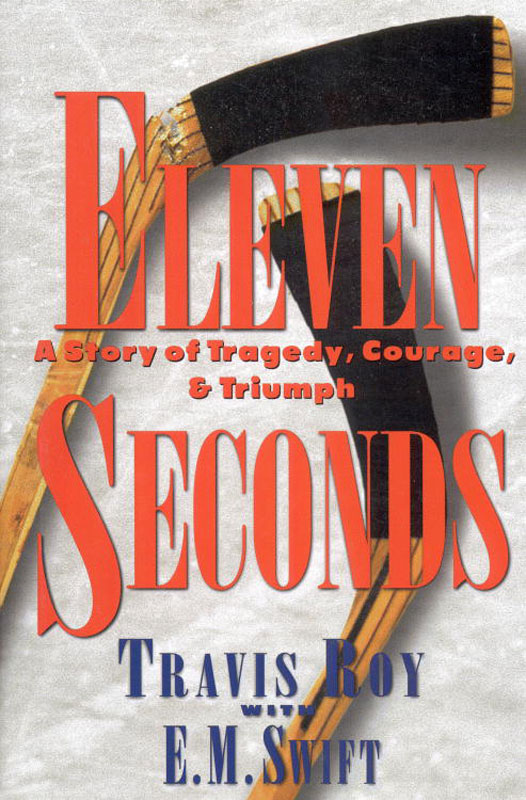

Copyright 1998 by Travis Roy and E. M. Swift

Afterword 2005 by Travis Roy and E. M. Swift

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

First eBook Edition: January 1998

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

ISBN: 978-0-446-55325-4

To Mom, Dad, Tobi, and Keith

You have given me my strength to get me through the toughest times of my life. Because of you I am able to look forward to my future and hope for many more times of happiness together. My pride and love for you are immeasurable.

To Maija

I knew you were special from the first time I kissed you. You have given me the happiest times of my life, and you have held my hand and pulled me through the worst times. We have been through a lifetime of emotions together, and nobody can take that away. No matter what happens in our futures, you will always have a piece of my heart. I love you.

To Coach Parker

Your words and support have been as valuable to me as anything I will ever have. I look forward to each and every moment I spend with you. Thank you for being there.

I would like to give my most sincere thank-you to the thousands of people who have helped me, my family, and Maija through the past year and a half. Individually I would like to thank Ed Carpenter, Ed Swift, Alan Mooney, Ed Anderson, Century Bank, Freedom Capital, Palmer and Dodge, Woolf Associates, and the Friends of Travis Roy. We would never have been able to get through this without you.

Sometimes, while seated in my chair high above the ice at the south end of the arena, I find myself staring down at the corner to the left of the visitors goal, knowing thats where it all ended, and where it all started. Just staring.

And sometimes, before a game, I sit in the middle of the locker room and ask myself, Is this real? Is this really happening?

I am in one of my favorite places in the world, watching my teammates get ready to go on the ice, in a wheelchair. My locker stall is there, fourth from the right, with my nameplate above it. My stuff is still hanging in the stall: gloves, shin pads, pants, helmet. No one is dressing there. I hate looking at an empty stall. Anyones empty stall.

The music is blaring from the sound system, pumping my teammates up for the game. The VCR and television, the ones on which we study videotapes of the other team, are behind me, but I can see them if I turn my head. The big red carpet covering the locker-room floor still looks new, and my teammates are stretching while sprawled upon it. Chris Drury. Mike Sylvia. Dan Ronan. I watch them instead of limbering up with them. There is a nervous tension in the room, but I am not part of it. Its like Im stuck in a dream.

Strangest of all for me is the large photograph hanging beside the door, a picture of me in my Boston University uniform lining up for a face-off at center ice, the only face-off of my college careereleven seconds before the accident. You cant miss it as you walk out that door on your way to the ice. You are not supposed to miss it.

None of it seems real. Its all so dear and so familiar, and yet its exactly like a bad dream. Most of my life now seems like a dream, while most of my dreams seem like real life: the life I knew and still hope for. I am always walking in my dreams, or running, or riding my bike. Or Im skating, and my life is going on as Id always planned. Even when I dream Im in a wheelchair, Im always getting better, moving my hands and arms around. Picking things up. Moving my fingers. I am about to rise up and walk free. I never dream of myself getting worse, or existing the way I am now. They're enjoyable dreams, and I love going to bed. Im always hoping to dream when I go to sleep. The more real the dreams the better. Sometimes I want to dream the rest of my life away, and not wake up and have to get back into this chair.

What has happened to me doesnt really happen to people. Thats what Im thinking as I watch my teammates prepare for a game. To reach your lifelong dream, then eleven seconds later have a freak accident, a one-in-a-million accident, that leaves you in a wheelchair for the rest of your life. That only happens in dreams. And I think, How could it have happened? Not why did it happen, which is what a different sort of person might ask. How could it happen? To me, who was always such a fine, well-balanced skater?

I wonder that every time I go into the BU locker room. I go through that exact thought process.

I still love hockey. Im not angry at the sport. Im not angry at anything, or anyone. What I am is sad. Sad that it all ended so soon. Sad that, without a medical breakthrough, I wont be able to teach my children what my father taught me. Sad that I wont be able to play the game that brought me such joy anymore, a game I played better than I did anything else. Im not so disconsolate that I wont get through this. I dont need, or even like, sympathy. But I miss excelling at something. I miss being part of a teampart of the jokes, part of the joy and the pain, part of the locker-room camaraderie. I miss the pure physical act of skating, of flying over the ice.

My earliest memories of skating are of the power-skating clinics taught by my dad, Lee Roy, and a man named Carl Walker at North Yarmouth Academy in Maine. That was the rink my father managed when I was growing up. My father was Mr. Youth Hockey in southern Maine, founding the Portland Youth Hockey Association in 1972, when basketball was the winter sport of choice throughout the state. Over the years he managed four different rinks in Maine, including the Cumberland County Civic Center, coaching kids from Mites to college age. He ran summer hockey camps, sharpened skates, drove the Zambonis. In 1972, when he started, there were six high school teams in the state. Today there are 43.

You cant play hockey if you cant skate, my father would tell me. We did nothing at those clinics but work on our edges, learning to shift our weight to the inside edge, to glide, to push off, to stop. I was five, six, seven years old. These clinics were not fun. You never saw a puck. The only fun drills were when you did barrel rolls, falling, tumbling, and getting back up. But I loved being out on the ice. Dad didnt have to tell me twice to grab my skates.

My dad is a big man, about six foot two and 230 pounds, and firm. He always wore the same sweat suit, a black one, with straight legs and red and white stripes up the side. A practical outfit for a practical man. He had three or four whistles, and a bag full of pucks. Hed gather the stuff together, then wed head off to practice, twice a week, from 6 to 7 P.M. I was four years old when I started playing organized hockey, and I spent five years with my fathers Mites team, which included kids up to eight years old. Other youngsters would come and go, but I stayed, a Mite for life. For years I was the youngest and the smallest, but because of all those tedious power-skating schools, I could skate as well as anyone else. Not necessarily faster. But I was better balanced. More agile. One season Dad would have me play forward, the next year defense. I learned both aspects of the game.