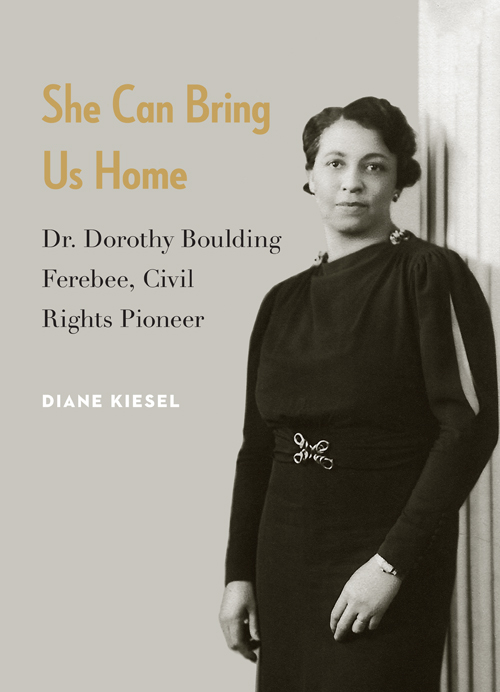

This lovingly crafted biography brings to life the remarkable tale of a powerful but overlooked twentieth-century advocate for women and racial equality. Born at the end of the nineteenth century, the descendant of slaves who fl ed to Boston, Dorothy Ferebee took her Tufts Medical School diploma to the nations capital to serve the neglected needs of African Americans living in poverty.... In Judge Diane Kiesels capable hands, Ferebees life as a national civil rights leader is given long-overdue recognition.

James McGrath Morris, author of Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press

This meticulous account of the life of one of twentieth-century Americas most influential African American women, a doctor whose contributions to public health, civil rights, and womens reproductive freedom were vast, is long overdue.... In this engrossing work of investigative biography Diane Kiesel reveals that success was achieved at great personal cost and masked a secret tragedy.

Nina Burleigh, author of The Fatal Gift of Beauty: The Trials of Amanda Knox

Dorothy Ferebeeground-breaking physician, civil rights champion, feminist advocatewas a legend in her own time but is largely unknown in ours. Now Diane Kiesel brings alive this extraordinary woman whose private life was as tortured and heartbreaking as her public persona was exemplary and heroic. A compulsively readable exploration of the price women pay for greatness.

Ellen Feldman, author of The Unwitting and Scottsboro

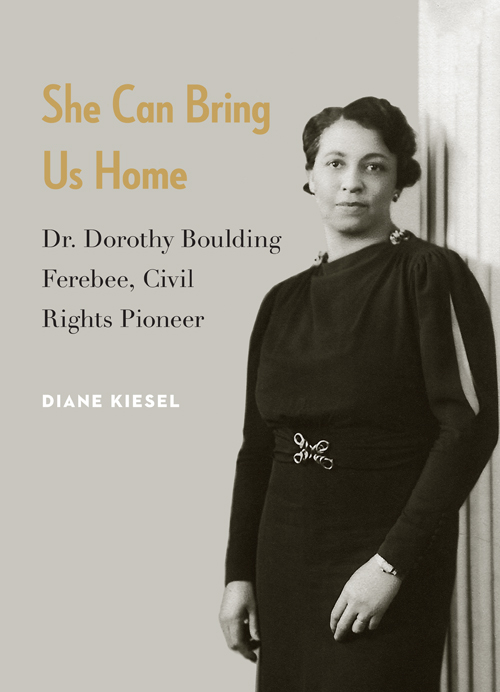

She Can Bring Us Home

She Can Bring Us Home

Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, Civil Rights Pioneer

Diane Kiesel

Potomac Books

An imprint of the University of Nebraska Press

2015 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Cover image is from the interior

Author photo courtesy of John Halpern

All rights reserved. Potomac Books is an imprint of the University of Nebraska Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kiesel, Diane.

She can bring us home: Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, civil rights pioneer / Diane Kiesel.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61234-505-5 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-61234-758-5 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-61234-759-2 (mobi)

ISBN 978-1-61234-506-2 (pdf)

1. Ferebee, Dorothy Boulding, 1898?1980. 2. African American civil rights workersBiography. 3. Women civil rights workersUnited StatesBiography. 4. African American physiciansBiography. 5. Women physiciansUnited StatesBiography. 6. Howard UniversityHealth ServicesBiography. 7. National Council of Negro WomenBiography. 8. African AmericansCivil rightsHistory20th century. 9. African AmericansSocial conditions20th century. 10. African AmericansHealth and hygieneHistory20th century. I. Title.

E185.97.F39K54 2015

323.092dc23

[B]

2015002751

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

In Memory of Dorothy Boulding Ferebee Jr. (19311950) and Claude Thurston Ferebee II (19311981)

It was then that we initiated the first mobile health clinic in the country.... Those at home who thought we were down in Mississippi having a big time should have been there to see what difficulties we experienced. This was before the days that the WPA built decent roads in Mississippi. The roads were nothing but mud or shale and sand and rocklittle rocks and gravel. And when we traveled we encountered nothing but dust. One couldnt see the car in front. No routes were marked, you didnt know where you were. But fortunately, theres been something about me that I can always come back from where Ive been. So when the members of the team noticed that even without markings or signs, I could always get home, they made me the leader of the group. Because they said, Wherever weve been, she can bring us home.

Dr. Dorothy Boulding Ferebee

Describing her travels in 1935 as medical director of the Mississippi Health Project for the Black Women Oral History Project, December 28 and 31, 1979, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge MA

Contents

Between 1977 and 1981 the Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, recorded the memories of certain African American women, age seventy and older, which became known as the Black Women Oral History Project. Among the subjects was Dorothy Boulding Ferebee, who was interviewed at her home on December 28 and 31, 1979, by Merze Tate, a historian at Howard University. It was the most detailed interview she ever gave. The original tape is on file at Radcliffe, and copies of the official transcript of that interview are available at major research libraries around the country. The interviews were also published in book form in 1991.

I interviewed Ruth Edmonds Hill on August 2, 2011, who as Oral History coordinator for the library, supervised the Black Women Oral History Project. Ms. Hill said that each subject was given the opportunity once the interview was completed to review a transcript and make editorial changes. Unfortunately Dorothy was gravely ill when she granted the interview, and died before she was able to edit it. Therefore, the review and editing fell to her son, Dr. Claude Thurston Ferebee II, who was suffering from cancer and died a year after his mothers death, and to Dorothys daughter-in-law, Carol Ferebee. In addition, Dr. Tate did her own editing and revising of those portions of the interview she thought were inaccurate or needed further clarification. I have listened to the tape and reviewed the edited transcript. The taped interview is rambling and repetitive. At times, Dorothy seemed confused about events in her life. Certain words and phrases have been changed in the official transcript, which is tighter and easier to understand than the original interview. The Schlesinger Library considers the edited transcript to be the official interview, and therefore, when I quote Dorothy from this interview, I am quoting from the official transcript. In my opinion the essential meaning of what she said was not altered by the editing process. But where there seems to be a problem with either Dorothys memory or the editing, I have pointed it out.

The terminology for African Americans has changed repeatedly with the times. Words such as colored and Negro, now archaic, were once widely in use and are used in this book when appropriate for the narrative. Unfortunately, like all African Americans, Dorothy and her contemporaries were also subjected to vile racial epithets. Where necessary for historical accuracy, those words are also used.

In her homage to librarians, This Book Is Overdue, Marilyn Johnson wrote, They want to be of service. And theyre not trying to sell us anything. I could not agree more. This book could not have been written without the help of many librarians, curators, and archivists. In recognition for all their dedication, hard work, and kindness, Id like to thank David Smith, former senior librarian, New York Public Library; William Inge, Sargeant Memorial Room, Norfolk Public Library; Joellen ElBashir, Clifford Muse, Tewodros Abebe, Ida Jones, and Richard Jenkins, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center and the Howard University archives; Kenneth Chandler, National Park Service, Mary McLeod Bethune National Historic Site, National Archives for Black Womens History; Patrick Kerwin, Jennifer Brathvode, Joseph Jackson, Bruce Kirby, Lewis Wyman, and Jeffrey Flannery, Manuscript Reading Room at the Library of Congress; Mark Bartlett and Carolyn Waters, New York Society Library; Kelli Bogan, Colby-Sawyer College; Karen Green, New England Law School; Jason Wood, Simmons College; Meghan Lee-Parker, Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace; Dale Neighbors, Library of Virginia; Christopher Banks, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum; Virginia Lewick, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; Yevgeniya Gribov, Girl Scouts of the USA; Ellen M. Shea and Ruth Edmonds Hill, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute; Amy LaVertu, Tufts University; Stephen E. Novak, Columbia University Medical Center, A. C. Long Health Sciences Library; Adrienne Sharpe, Beinecke Library, Yale University; Ashley Mattingly, National Archives and Records Administration; Crystal Finley, Bethune-Cookman College; Peter Weis, Northfield-Mount Hermon School; Rachel Saliba, Meg Rand, and Joy Jones, Tilton School; Kimberly Springle, Charles Sumner Museum and Archives; Marta Crilly, City of Boston archives; Richard Baker, U.S. Army Historical Center, Carlisle, Pennsylvania; Christopher Harter, Amistad Research Center, Tulane; Debra Kimok, Benjamin Feinberg Library, Plattsburgh State University College; Steven G. Fullwood, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture, and Julia Jackson.