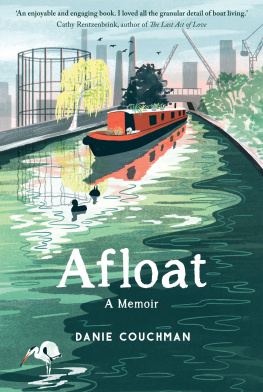

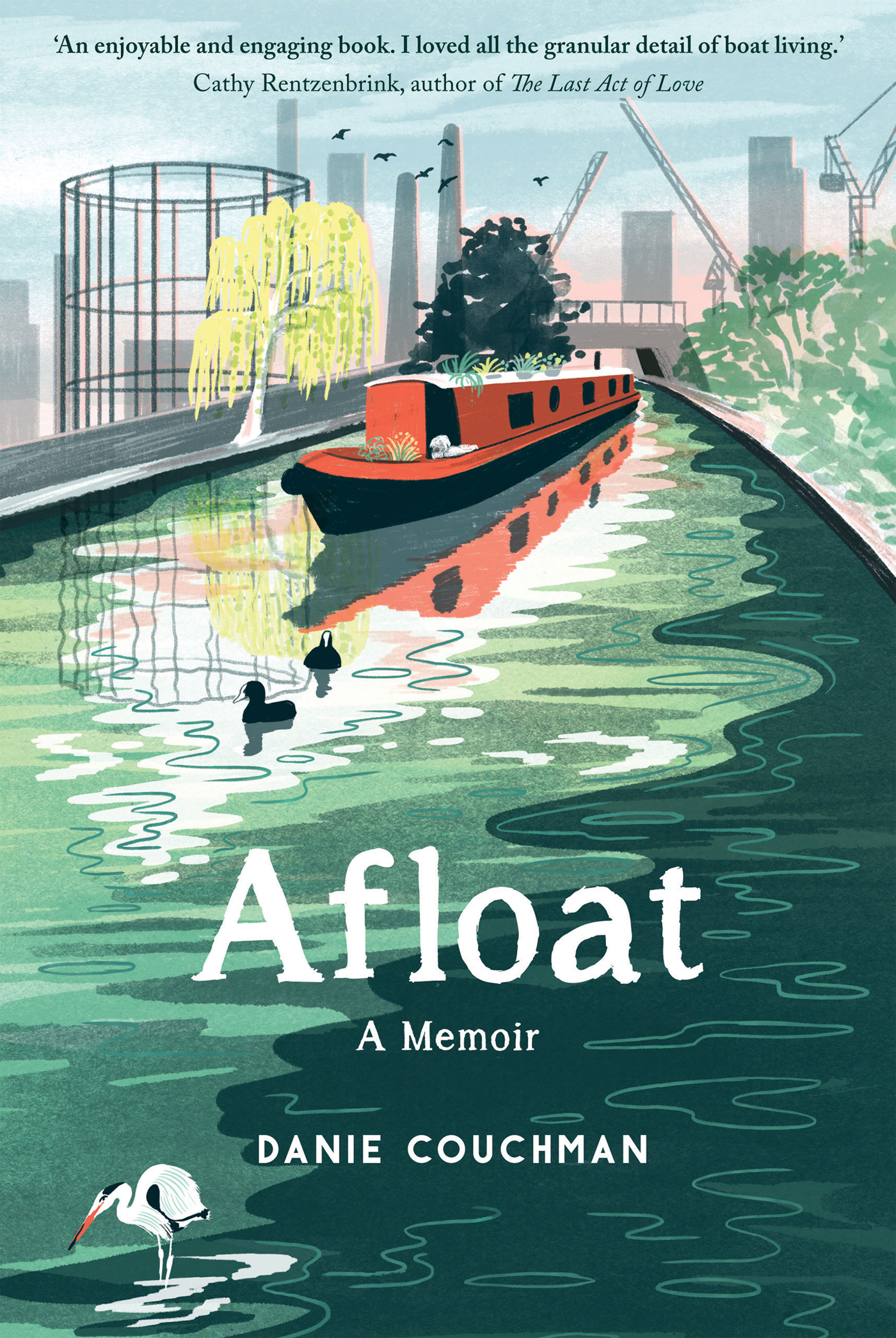

Publishing Director Sarah Lavelle

Commissioning Editor Susannah Otter

Copy Editor Sally Somers

Designer Gemma Hayden

Illustrator Eleanor Taylor

Production Director Vincent Smith

Production Controller Sinead Hering

Published in 2019 by Quadrille, an imprint of Hardie Grant Publishing

Quadrille

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

quadrille.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Cataloguing in Publication Data: a catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright Danie Couchman 2019

Illustrations Eleanor Taylor 2019

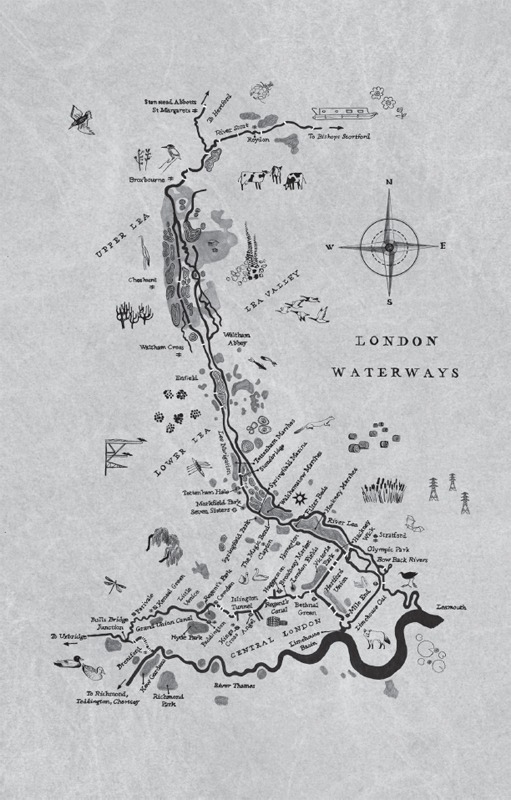

Map Illustration Maisie Noble 2019

Design Quadrille 2019

eISBN 978 1 78713 349 5

For the flotilla and my family, with lots of love

CONTENTS

When I was eleven, I stood at the top of the steep staircase with all the black and white photos Dad had taken of my younger brother Ben and me hanging along the walls. I was looking down at the front door, where Dad stood holding a brown leather suitcase, the type a kid being evacuated in the war might have had. He said goodbye. I knew, by the way he said it, what was happening, and through sobs begged him not to leave. But that was that. He was gone. Mum told me I found the number of the other woman and called her a bitch down the phone. I dont remember that bit.

Life had been good until that point. It had been nomadic, and wed never stayed long enough in one place to be able to say that was where I was from, but I had loved the adventure. My mum told me that in the moments after I was born, my dad young and lean took me into his arms and showed me around the RAF hospital where Id entered this world. Mum, twenty-five, small but strong, was left lying in the hospital bed exhausted and baby-less. I imagine her chocolate-brown permed hair looking wildly perfect, her cheeks beautifully blushed.

It was the summer of 1987, and we were in Germany where Dad had been posted with the British Army. Wed be there a short while before moving on again. We moved to two places in England whilst dad trained to become an Army photographer. Belgium would be next, where Id rescue ducklings from the drain at the back of the garden, and the symbol above my coat peg at the local nursery where everyone spoke French was a smiling crescent moon. My little brother Ben was born. Three months later, Dad was posted to Belize in Central America for six months. He sent me drawings of jungles and sea creatures. Then, when I was five, on we went to Northern Ireland, to a town six miles west of the daily IRA bomb explosions, deadly gun battles and violence of a troubled Belfast. We lived on a street where the ends of rainbows landed, and Id walk home from school with my friend Catherine and her older brothers, my voice quickly picking up their thick Northern Irish accents, with tiny pink seashells in my pocket that Id stolen from a classroom. Standing on kitchen chairs so we could reach the gas hob, wed heat up a tin of soup by ourselves for tea at their house.

Sometimes, men in camouflage with guns would run through our back garden where Id secretly planted a magic bean. Mum would check under the car before driving and not stop at red lights, and Dad would not take the same route twice in a row. A piece of flint got stuck in my knee when I fell off my bike. I still have the scar. My classmates wrote me goodbye letters when we left for England, promising to always be my friends. The army kids in the British barracks that we moved to next tried to make me say my first swear words. They were different to the other children Id met. Before, wed always lived on civilian streets and had local friends. Here, all the kids knew each other, they moved together in one big unit, their mums were young, their dads all part of the same regiment. They were friendly, but more wild. One girl took my shoe and threw it in the bin. Another girl, who was younger than me and had a pet Staffordshire Bull Terrier that shadowed her wherever she went, went for a poo on the stairwell because she was locked out of home. My soft Irish voice stood out, and within a few days I was speaking with a harsh and exaggerated South London twang, dropping my Ts and Hs. Have became av, water became wa-er. I stole 20p pieces from the bits and bobs drawer to buy picknmix for Ben and me from the corner shop where the school bus picked us up each morning, and my new best school friend, Pavan, lived above the post office.

Each time we moved, Dad went ahead, and Mum packed up the house, got us two little ones on a plane, and then into a new local school. By the time I was seven Id lived in eight homes and four countries. We were itinerant, with never enough time to establish foundations. Like a hardy plant that can grow in the crevices of rocks, I grew up clinging on to whatever surface I could find. I learned to grab onto whatever solid ground there was, soaking up all the goodness that the new land had to offer before we moved on again. It made me adaptable. It was perhaps this life of transience and constant change that would later make me recklessly open to new experiences. Perhaps it was this life that led me to a watery world in search of adventure and belonging.

It was late May 2013 when I found the canal. I remember the air finally felt warm, and the trees lining Londons streets had begun to blossom. I was twenty-five, and living in my seventeenth home: a house in Hackney that I shared with three men I didnt know, and a sofa-crasher. My room was small and came with a broken bed and an old used mattress which took up most of the space, and a small wardrobe. It was next to the shared bathroom and lounge, which had a big TV and fast Wifi. It was in a neighbourhood of cheap chicken shops, Afro hairdressers, late-night pubs and Victorian houses with multiple door numbers and bins out front. After bills, this home in East London cost me around 900 each month. I had lived in six homes in London in four years. When I first arrived in the city, not knowing anyone or anywhere, I lived in a house in Ealing with four women I hadnt met until the day I moved in. My tiny room overlooked railway tracks and a constant whizz of trains. The landlord wouldnt let me put up curtains or a shelf so I moved out quickly, into a two-bed flat in Shepherds Bush, with a boyfriend ten years older than me who had a little girl who sometimes stayed with us. We shared the flat with a Spanish and a French girl about my age. The girls both worked nights in hotels so they cooked in the early hours of the morning, pans clattering. Live music and shouting from the bar below sounded up through the floorboards. I would step out onto a roof through the bedroom window and look out over the madness; screeching sirens and the constant rumbling drone of cars, street cleaners and rubbish trucks. Every night I slept with ear plugs in, every night my sleep was still disrupted. With no dining room or lounge, we ate breakfast and dinner in the bedroom. We moved out, and my boyfriend and I stretched our budget to live in a one-bed flat on a quieter street in Chiswick. After just a few months, the landlord decided to sell and told us we had to leave. We broke up. Then there was a flat with another girl I didnt know. At this one, the landlord would come by without warning to get things from his shed. Eventually I ended up in the house-share in Hackney. I felt an affinity for Hackney, far more than West London. My grandparents and great-grandparents had lived in East London, and something about the streets on this side of town made me feel more at home. They felt alive.