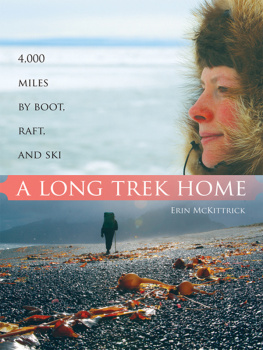

4,000

MILES

BY BOOT,

RAFT,

AND SKI

A LONG TREK HOME

ERIN MCKITTRICK

THE MOUNTAINEERS BOOKS

is the nonprofit publishing arm of The Mountaineers Club, an organization founded in 1906 and dedicated to the exploration, preservation, and enjoyment of outdoor and wilderness areas.

1001 SW Klickitat Way, Suite 201, Seattle, WA 98134

2009 by Erin McKittrick

All rights reserved

First edition: first printing 2009, second printing 2010, third printing 2011 No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distributed in the United Kingdom by Cordee, www.cordee.co.uk

Manufactured in the United States of America

Copy Editor: Joan Gregory

Cover Design: Mayumi Thompson

Interior Design: Jane Jeszeck, www.jigsawseattle.com

Cartographer: Bretwood Higman

Photographers: Erin McKittrick and Bretwood Higman

Cover photographs: Top: Erin looks out across the swirling sea ice of Knik Arm. Bottom: Hiking the volcanic rock beaches of the Alaska Peninsula in a flash of evening sun

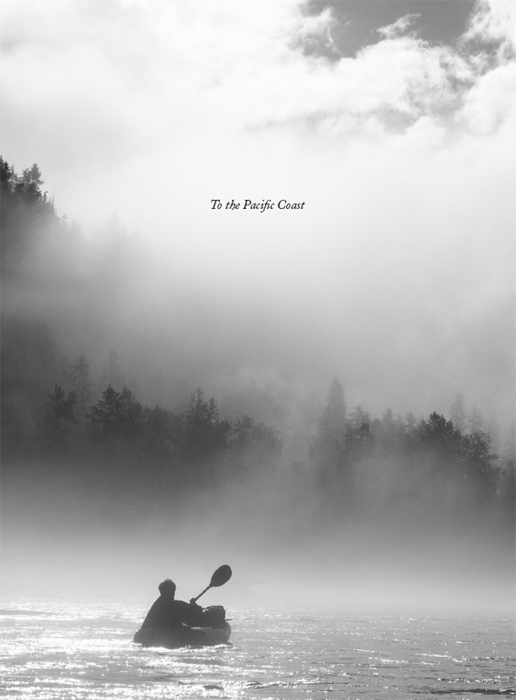

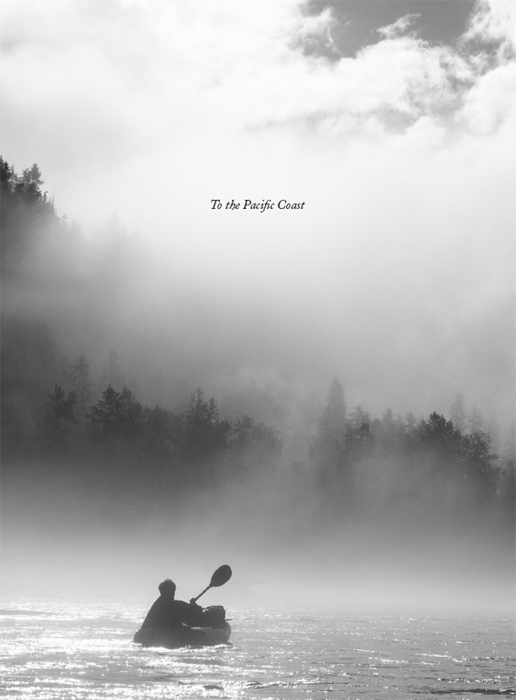

Frontispiece: Banks of fog obscure the steep mountains lining the Chikamin River in Alaskas Misty Fiords.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McKittrick, Erin.

A long trek home : 4000 miles by boot, raft, and ski /

Erin McKittrick. 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-59485-093-6

1. Northwest Coast of North AmericaDescription and travel.

2. HikingNorthwest Coast of North America. 3. Rafting (Sports)Northwest Coast of North America. 4. SkiingNorthwest Coast of North America. 5. McKittrick, ErinTravel. I. Title.

F852.3.M39 2009

979.5dc22

2009028197

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper

ISBN (paperback): 978-1-59485-093-6

ISBN (ebook): 978-1-59485-392-0

CONTENTS

Prologue: LEAVING

THE PLAN WAS TO WALK, to paddle, and to ski. To leave Seattle and reach the Aleutian Islands under our own power. To travel not just in summer, but also through an entire Alaskan winter. To travel more than 4,000 miles.

We were about to do something audacious. We were about to do something no one had ever done before. I couldnt grasp the full extent of it any more than could our most skeptical questioners. We planned it, we breathed it, we believed it, but it seemed as though we spent all our time proclaiming a plan that didnt feel real.

I picked up a thick loop of aluminum wire from the top of the pile, turning it over in my hand. Should I wait and ask Hig what to do with it? Maybe hed argue to keep something so useful-looking, but if I recycled it now, hed never notice. Undecided, I set it aside.

Piles of stuff covered the floor of our living room, our dining room, our bedroom, and our kitchen. More piles of stuff sat on the lawn, along with most of our remaining furniture, decorated with Free signs. A few fluffy white feathers drifted around the corners of the dining room, escapees from when wed sewn a down quilt a few weeks earlier. Colorful scraps of fleece, nylon, webbing, and insulation left over from gear construction were bursting out of a cardboard box.

I glanced up the street, looking hopefully for any sort of delivery truck. We were still waiting on a few crucial pieces of expedition gear. If they didnt come soon, we would have to figure out some way to get them en route. We still needed the packraftsthe five-pound inflatable boats that would ferry us across the many expanses of water we would encounter. We still needed paddles. We still needed dry suitsour only outerwear for the trip. I didnt know how any of these items could possibly catch up with us if they didnt come before we left. But there wasnt much I could do. The invitations were out. We were leaving on Saturday, June 9, 2007, at noon. And that date was now less than a week away.

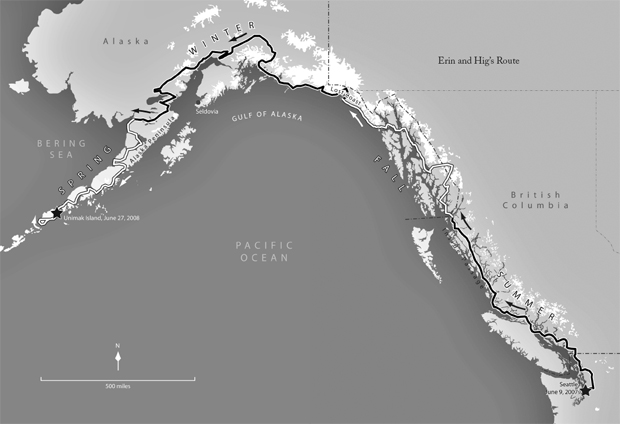

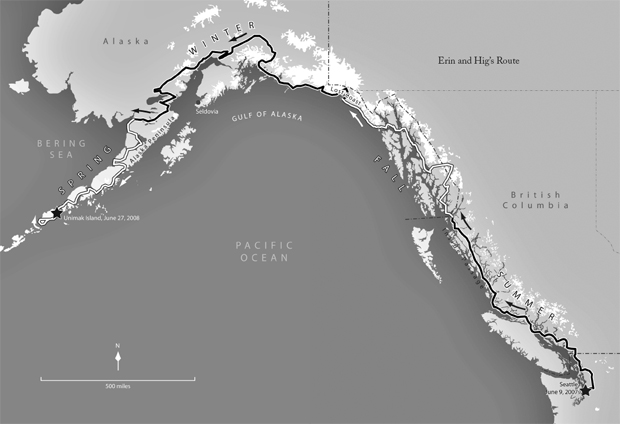

On computer maps, my husband, Hig, and I had drawn an imaginary linea bold black stripe across the digital landscape. Beginning at our Seattle doorstep, the line snaked back and forth between the Cascade Range and Puget Sound and then headed north to the Canadian border. From there, our route followed the Inside Passage, weaving through the protected network of inland waterways and forested islands that stretches from Puget Sound through coastal British Columbia and Southeast Alaska. Where the Inside Passage ends, we planned to continue on to the Lost Coast, a narrow strip of surf-battered shore between the Gulf of Alaska and the mountains and glaciers of the St. Elias Range. We would then make our way through Prince William Sound and along the edge of the Chugach Mountains to Anchorage. At Anchorage, our northern-trending route would turn southwest, weaving back and forth between the Pacific Ocean and the Bering Sea, the two coasts of the volcanic Alaska Peninsula. Finally, at the tip of the Alaska Peninsula, we would cross to Unimak Island, the first in the Aleutian chain. Our intricate plan would take us through urban streets, dense rainforests, sandy beaches, glacial rivers, windswept tundra, snowy valleys, protected inlets, wild oceans, and the flanks of volcanoes. Our 4,000-mile journey had been a year in the planning. At the time we left, we expected our trip to take nine months.

Hig and I met at a Minnesota college. I had grown up in Seattle; Hig was raised in the tiny Alaskan town of Seldovia. We bonded over our joint love of scienceme studying biology while he studied geology. But our relationship was cemented in the Alaskan wilderness.

When I graduated from college, we trekked 800 miles down the Alaska Peninsula. It was the beginning of an addiction. Each summer we were pulled north for a new adventure. In the seven years since that first journey, we had traveled over 3,000 miles through the Alaskan wilderness. And as we journeyed, our dreams grew grander and grander, seeking only the time to be realized. Less than twenty-four hours before we planned to leave, Hig graduated with his PhD in geologic hazards. It was a break in our lives. With no commitments, we had the space to do something truly momentous.

From the intricate terrain of mountains, ocean, and glaciers, to the abundant wildlife, to the friendly outposts of civilization, the northwest Pacific coast was our favorite place on Earth. And though we had seen only a few small pieces of our proposed 4,000-mile route, we thought of it all as home ground.

This region has a wealth of natural resources: forests, fish, oil, coal, and metals. It has vast stretches of wilderness, vast swaths of industrial development, and vast environmental battlegrounds. On this broad journey, we wanted more than just an amazing adventure. We hoped to get the big picture of what was happening in this region we loved. How could the people living here thrive alongside the natural world around them?

We saw ourselves as explorers. And we gave ourselves one simple rule for the journey: No Motorized Transport. In order to get the most complete picture of what was going on, we had to experience everythingnot just the amazing wild places, but also the clear cuts, suburbs, and noisy urban landscapes on our path. Whether walking, skiing, or paddling, every inch of this journey would be under our own powerviewing the world at human speed.

Printed on recycled paper

Printed on recycled paper