Dora Akunyili once thrust a rosary into my hand.

Keep it with you at all times to protect you, because success brings envy, she said, and added, as though to brook no argument, It was blessed in Rome.

A slate-coloured rosary with a shiny crucifix. I have kept it since, part comforting superstition and part tribute to a woman who was one of the best public servants Nigeria has ever had.

As the director general of NAFDAC, the food and drug regulating agency, she fought the importers of fake medicines and the makers of unsafe foods, unnerving business interests that had long been complacent in their corruption. They went after her, and she survived assassination attempts; a bullet once narrowly missed her head, striking her ichafu. She was radical because she had integrity in a system that was unfamiliar with integrity. A businessman once told me that Dora Akunyili was the only public official he respected. She smiles with you but she will insist that you do the right thing, he said.

She was kind and vigorous, and when she spoke, she widened eyes as though to better convey the force of her conviction.

Nigeria lost one of its best when she died.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Author

Part I

Dora

1954 1972

One

A name is both a prayer and a story.

I was six, my thick, tight coils in neat plaits, my bright face accentuated by my fair complexion, and my mind mature enough to understand that something major was happening.

In the late 1950s and early 60s, in the face of Nigerias transitions, Papa would explain to me the history of colonization and that hitherto the country hadnt been free. With this, he often reminded me of the transient nature of things one moment we were a part of Great Britain and with the stroke of a pen we were not. He underscored his message with his experiences and the drastic changes in his own life, having gone from riches to penury after his fathers death and then again to riches in Makurdi as a business tycoon. He always returned to the emphatic reminder that no one knew tomorrow and as such nothing was to be taken for granted.

He loved to talk about change as captured by history and the passage of time. He spoke of Igbos and the great traditions that had shaped the people, like the very language itself. In the Igbo culture of southeastern Nigeria, he said, the power of words has always mattered, for words form stories, and stories shape mindset and reality.

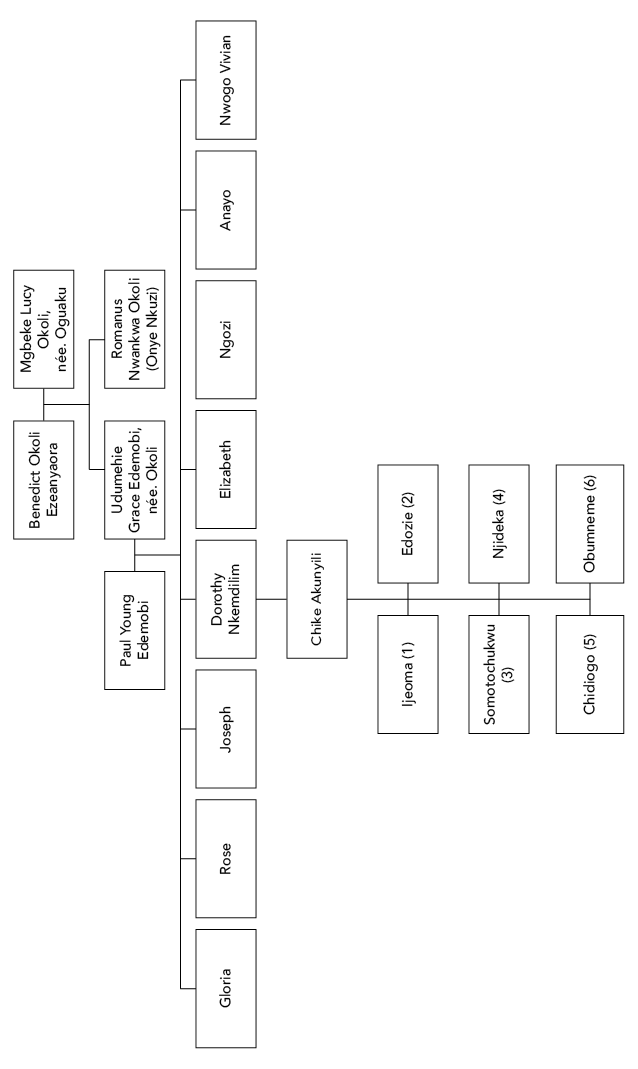

When I was born in 1954, a kola nut was broken in honour of my birth, and isee and so it is was chorused along with prayers for a long and prosperous life. To support these prayers to take root, I was given the name Dorothy Nkemdilim Edemobi. Dorothy means gift of God, and Nkemdilim, let what is mine be unto me; in other words, may my destiny be fulfilled. Edemobi is short for edeimobi, meaning I rest my soul. My name in full was the prayer for the gift of God whose destiny will be fulfilled so that I may rest my soul a heavy name for a newborn girl.

Papa was a great storyteller and he loved to share details of my birth. One look in your eyes, he said, and I knew you were special.

Some children are drawn to a toy or a blanket; I was attached to my father. I loved to be around him, and I always sought out his presence and drank it in fully.

The affection was mutual. I was the fourth born of eight, but Papa lavished me with his attention. He insisted it was because I was very intelligent; I suspected that it was because I loved listening to his stories the most.

He liked to sit outside on the back porch of our home in Makurdi on the south bank of the Benue River, watching the day slowly turn to night, swatting away mosquitoes as we both listened to the sound of birds overhead saying good night to the day that was. It was his quiet time, and everyone knew not to disturb him, including me. I would sit curled against his chair, my legs sprawled out on a mat, taking in the lush green that surrounded the compound. I was happy to wait in silence until he felt ready to break it. In this setting I would listen to him share tales from times past, bringing people and places to life with each word, drawing me into unknown worlds.

One of my favourite stories was that of how Papa met Mama. I had heard the story so often I felt like I too had been there.

It was 1939. Afa Ezi was a colourful festival that attracted dozens of young girls and their suitors from Isuofia and surrounding villages in Anambra State. As it coincided with the full moon, Afa Ezi merged into Egwu nwa the dance of the moon.

In the light of day, the main attraction of the festival was the young women dancing in intricately choreographed sequences across the market square, naked breasts soaking up and reflecting the sun, colourfully clad bottoms gyrating to the music and attracting the attention of potential suitors.

Udumehie Grace Okoli was one of the women. All would agree that she was beautiful, with her coveted light skin, oval face, and pointed nose. My father, Paul Young Edemobi, followed her every move with his eyes, noting her confidence, her modesty, her beauty, and the grace of her movements. A young man from neighbouring Nanka, he didnt have much to offer in terms of a dowry, but he didnt let that stop him from dreaming.

He had seen Grace a few times in Afudo, a common market frequented by residents of Nanka and Isuofia alike. And he had gone every market day since his first sighting, hoping to catch another glimpse of her. There was something almost ethereal in her movements, like a Mami Wata. When he found out her name was Grace, he was even more besotted.

The day after Afa Ezi, he called at the Obi of Mr. Benedict Okoli Ezeanyaora, a medium-sized round hut with freshly plastered mud and newly harvested thatch adorning the roof and hanging over to provide shade.

It was Mgbeke Lucy Okoli Graces mother, whom everyone called Nne, meaning mother, in recognition of the birth of her first son and her role as the matriarch who met him at the entrance of the Obi. She was stooped low, a dull-coloured wrapper held by a double knot tied under her armpit, humming as she deftly shelled melon seeds over a large basket. A sharp woman, she recognized their guest as one of the men from the festival and as the son of the late Ogbueatghegwu, the fearless warrior from Nanka. She invited him to take a seat while she sought out her husband.

Benedict and Nne had just two children: Romanus, whom Nne called by his middle name, Obidigwe, and Udumehie Grace, whom both Nne and Benedict called Udum for short.

Paul Young was able to convince Graces parents of his interest and worthiness. Graces father gave his blessings in words that stayed with Papa through the years: I am sorry for the misfortune that befell you when your father died. I am happy that you havent allowed it to hold you back. You are just starting your life, and the world is changing so quickly. I am sure that the future is bright for a man with your determination.

Benedict liked a man with vision. He too had had to learn to fend for himself from a young age as one of thirty children. He recognized in Paul Youngs eyes the same fire, and he valued the articulated dreams of the impressionable man before him and, even more so, his meticulously argued plans for success beyond the borders of Igboland.

Next page