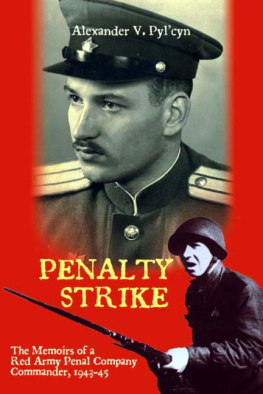

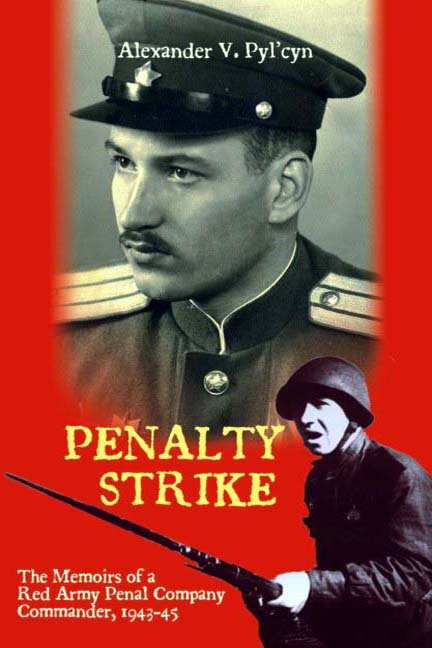

Dedicated to all shtrafnik officers and their commanders, from the 8th Detached Penal Battalion of the 1st Belorussian Front, who made it to Berlin on the difficult roads of war.

Helion & Company Limited

26 Willow Road

Solihull

West Midlands

B91 1UE

England

Tel. 0121 705 3393

Fax 0121 711 4075

Email: publishing@helion.co.uk

Website: www.helion.co.uk

Published by Helion & Company 2006

eBook edition 2011

Designed and typeset by Helion & Company Limited, Solihull, West Midlands

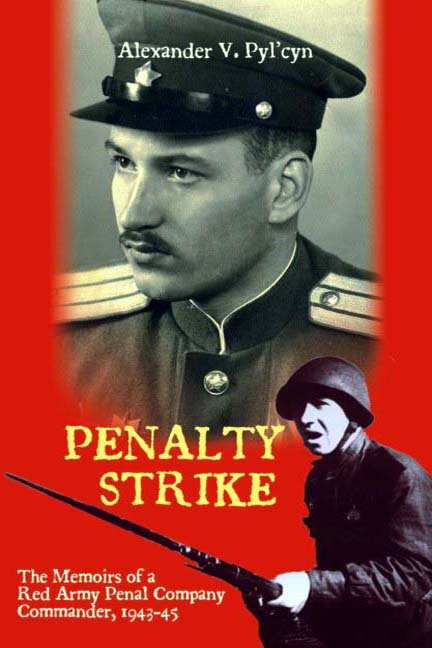

Cover designed by Bookcraft Limited, Stroud, Gloucestershire

Printed by Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire

Artem Drabkin 2006

Photographs Artem Drabkin 2006

Text edited by Artem Drabkin, translated by Bair Irincheev.

Publication made possible by the I Remember website (www.iremember.ru/index_e.htm) and its director, Artem Drabkin.

Hardcover ISBN 1 874622 63 9

Digital ISBN 9781907677533

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written consent of Helion & Company Limited.

For details of other military history titles published by Helion & Company Limited contact the above address, or visit our website: http://www.helion.co.uk.

We always welcome receiving book proposals from prospective authors.

I n 1923 I was born into the family of a railway worker in Russias Far East. Our home was so close to the railway, that when a train passed by the whole house would shiver, as if it was itself ready to leave on a long journey. We all got so used to this proximity of railway and noise, that when we moved to another house, far away from the railway, we could not get used to the silence, it seemed unnatural to us. My father, Vasily Vasilievich Pylcyn, was born in 1881. He was from Kostroma, but for some reason, either trouble with the police or an unsuccessful marriage, he had to escape to the Far East. He spoke about this matter very vaguely and unwillingly, but he even changed his last name. I believe his real last name was Smirnov. He was a rather learned person for his time. We had a vast library of classic Russian literature in our home. If I remember correctly, he was a foreman of railway workers and then a railway master. He was an extremely skilful craftsman. Sophisticated carved wooden furniture, a fair amount of metal cutlery, and all sorts of wooden barrels for pickling vegetables, were all things he made himself. He was so strict in family life that we children were afraid of his mere look at us, although he never hit us.

Despite the active role that he played in social life, especially in defence voluntary organisations, such as Osoaviakhim and others, he was never a member of the Communist party. In 1938 my father was arrested for negligence in repair of a railway. It almost led to the crash of a passenger train. He was sentenced to three years in jail. The sentence was considered by everyone to be just. He returned from jail immediately before the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. My father had a strange habit of talking aloud to himself. One time he said, out loud, that Hitler turned out to be smarter than all our genius leaders, and that the main leader, i.e. Stalin, merely screwed Russia. Someone heard this and informed the authorities. There were plenty of woodpeckers, or informers, in those days. My father was again arrested. In the same way as many other people, he was sent from the Far East somewhere to the North, or to Siberia, where he vanished for good.

My mother, Maria Danilovna, was 20 years younger than my father. She was from the family of a simple railway worker. He was Siberian, a real Russian, as they said in those days, chaldon Danila Leontievich Karelin. In those days the word chaldon was pronounced as cheldon in the Far East, and was interpreted by some people as cheloveks Dona , a man from Don River, i.e. a Don Cossack. It was much later that I learnt that chaldon actually meant a real Russian Siberian, not an immigrant from the rest of Russia.

My grandmother, on my mothers side, was Ekaterina Ivanovna. Her maiden name was Smertina. She was from Khakassia. My grandfather would tell us that he stole her from the neighbouring village of Khakassian. My mothers parents were illiterate, although Granny Kate could count money very well, almost without looking. My mother was also illiterate, but knew a great number of sayings and superstitions. I taught her to read and write when I went to the first grade of school, although I could read when I was only four or five years old. I insisted that she attended likbez , a liquidation of illiteracy study group, and I supervised her. My mother learnt the basics of literacy well. She could read, slowly but steadily, and write, although with some difficulty. She did not have much time or patience for more. However, that level of literacy was enough for her to learn a trade. She became an automatic-railway-point operator at Kimkan station, when the war broke out and women had to replace men in many trades. She also worked in that office for many years after the war.

Our family was not rich before the war. I think there were no rich families at all in those days. But we survived, even the tragic famine year of 1933, without losing anyone in our family. It was mostly the taiga that was supplying us with food. Our father was also a dedicated hunter and supplied us with game. I remember that during the winter it was especially hard. He would go into the taiga every weekend and bring back a couple of rabbits, or several squirrels, and sometimes wood-grouse. Thus, we were well supplied, and inclined to squirrel meat, which was quite tasty. As well as all that, father was processing, and turning in to the State, rabbit and squirrel furs, getting flour and sugar in return. Also, he would go on vacation in the autumn and go into the taiga to harvest Siberian pine seeds. He would bring whole bags of those seeds home, and extract excellent oil out of them with a press that he made himself.

Mother used remains of the seeds for making Siberian pine milk, by boiling them in water. She also used the seeds for adding to flour in making bread. Mother would bake bread from a small amount of flour, mixed with barley acorn coffee that one could buy in shops in those days, and crushed oats. The bread was dark black or brown, but it rescued us from starvation. Our family tradition of harvesting berries, wild fruits, plants and mushrooms, also rescued us. Those pickled and dried preserves protected us from hunger, and from scurvy that was widespread in the Far East in those days. From childhood we were taught to pick up mushrooms and berries, and knew them well. There were not many wild fruits in the Far East, except for wild Chinese apples as they were called. Jokers said that they were sold by glasses, not by kilograms, because they were so small. However, there were a lot of berries, from wild strawberry, to honeysuckle and wild grapes.

My father and grandfather knew how to make baskets. They fished in a nearby cold and fast river, not with a fishing rod, but with a specially shaped basket. Sometimes they would bring small fish, with such delicacies as graylings. During the spawning of salmon they would bring humpback salmons, Siberian salmons that weighed up to 68 kilograms! Of course, on such days we had plenty of red caviar, although at that time it was readily available from shops. All the seafood was boiled in soup or fried, and also smoked, pickled and dried for winter. Everything was used for food. It was that variety that helped us to survive long and cold winters, and maintained our Siberian health. It is probably due to those reasons that we survived the years of famine better than people in Central Russia or the Ukraine.