Chapter Two Bernsteins Westerns

Different genres have different demands. If youre doing a Western, your music will inevitably be tied to the scenery more so than the characters. Westerns tend to be simplistic: good guys [and] bad guys. Whats awesome is the scenery. I love writing that kind of music.

With the benefit of hindsight, this telling statement was completely accurate at the end of Bernsteins career. And while it applies wholeheartedly to The Magnificent Seven, it is less valid relative to the period for his earlier Westerns, when he was not as mindful of the surrounding scenery. Bernstein was quick to point out the differences between his film scores and those of his contemporaries, who wrote in a more conventional manner, specifically in his discussion of the music for Sudden Fear. Yet his scores for Westerns in the 1950s reveal an approach that was not much different from that of his colleagues, who employed similar musical clichs, from modal sonorities for the Indians to triplet rhythms for galloping horses.

However, Bernsteins music for his early Westerns exhibits some of the finer nuances of his compositional style and fore-shadows some specific elements that will differentiate The Magnificent Seven score from all others. As highlighted in the previous chapter, some of the salient features of Bernsteins compositional style include a preference for linear or contrapuntal writing, evocative orchestration featuring solo instruments (usually woodwinds), and engaging melodies. These are all present in his early Westerns; yet, as Bernstein continued to develop his style in this genre, he strengthened the melodic lines, increased the use of syncopation, and honed his sensitivity to dramatic characterization. Added to these enhancements was an increasing awareness of the power of composing music to evoke the surrounding landscape. A review of Bernsteins Western scores leading up to The Magnificent Seven will show that, although his fundamental approach to scoring was not new, a progressive trajectory may be traced, culminating in the music for The Magnificent Seven. These four scores Battles of Chief Pontiac (1952), Drango (1956), The Tin Star (1957), and Saddle the Wind (1958) demonstrate Bernsteins stylistic development from the prevailing approach to composing for this genre, to his score that would significantly impact subsequent Western film scores, as well as the world outside of the cinema.

Battles of Chief Pontiac (1952)

It is unclear if Battles of Chief Pontiac was scored during the time that Bernstein was greylisted, but it is clearly a low-budget film, especially since it is so brief (only seventy-two minutes). Written by Jack DeWitt and directed by Felix Feist, it was filmed in South Dakota and featured actual members of the Sioux tribe along with Lon Chaney, Jr. (19061973), who starred as Chief Pontiac. Chaney later said that this role was one of his favorites.

Technically, Battles of Chief Pontiac is not a Western, although it features several signifiers of the genre, such as conflicts with Indians and many outdoor scenes. It is chronologically situated too early for the standard Western, which takes places after the Civil War, and it is positioned geographically in the Great Lakes region, which lacks the necessary topography. However, Bernsteins score is classic in its presentation of Western musical clichs related to the Indians, in this, his only film that features Native Americans. In this film, Bernstein worked within the musical conventions of the Western, not yet applying his appreciation and knowledge of folk music. He communicated his focus on the dramatic by composing music that reflected the tragedy and the cruelty in the narrative, as well as the romance and natural simplicity in its setting.

Battles of Chief Pontiac is introduced as a historic drama set in Detroit when it was a fort during the Revolutionary War. The story, which is not wholly accurate, focuses on a cruel and vengeful Hessian colonel, one of the Germans hired by the British to fight the Colonials, who prides himself on eradicating the Native American population. When the colonel is assigned to Fort Detroit, he has blankets that are infected with smallpox delivered to Chief Pontiacs village as a gift, which causes an epidemic that wipes out half the village. Attempting to save the fragile relationship the British at the fort have forged with Chief Pontiac and his people is their one true American brother, ranger Kent McIntire, played by Lex Barker, best known for his role as Tarzan. Winifred (Helen Westcott), the daughter of a British gentleman and a captive of Pontiacs tribe, provides the love interest. Battles of Chief Pontiac is sympathetic to Native Americans along the lines of Broken Arrow, a much better film starring James Stewart and Jeff Chandler (as Cochise), which had been released two years earlier with music by Hugo Friedhofer. The scores of both films share musical gestures, including strongly rhythmic modal melodies for the Indians with solo woodwinds (flute, clarinet, or oboe) to represent their gentler side and quasi-folk melodies to signify the white men. In one scene, McIntire trades his horse for a canoe from an Indian woman, and during this entire scene we hear a solo flute play a spontaneous-sounding melody. This atmospheric evocation recalls the marriage scene in Broken Arrow, as well as similar peaceful settings of Indians in other Westerns.

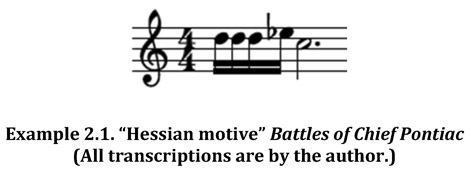

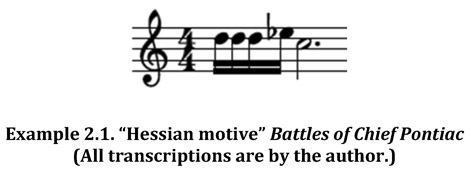

Most of the music in Battles of Chief Pontiac tends to follow the action, changing to reflect the visual and stopping during the dialogue. However, each group of characters in the film is generally accompanied by distinctive music. Bernstein identifies the treacherous Hessians with ominous, dark, and brooding music, often with a reiterated five-note motive (Ex. 2.1). We hear this motive, usually repeated in a descending sequence, when we are first introduced to the colonel and his evil ways.

Bernstein will recall this motive when composing the opening of The Tin Star, the villains theme in Saddle the Wind, and the theme for Calvera in The Magnificent Seven, all of which begin with the same notes. Romantic string music underscores the interaction between McIntire and Winifred, while the British soldiers are usually accompanied by quasi-diegetic music that simulates bugle calls or marching music. At one point, Bernstein composed a melody that sounds vaguely like The British Grenadiers. The Indians, however, are always accompanied by modal harmonies with syncopated rhythms and stylized drums. When we hear their distinctive music, we know they are nearby.

Bernstein was creative, and glimpses of his increasing talent for setting the proper dramatic tone are evident throughout this film. One example is the scene where McIntire, who is thrown into jail to prevent him from interfering with the Hessians strategy to eliminate the Indians, pretends to hang himself in order to escape. While McIntires scheme is completely unbelievable and awkward to observe, the music adds to the gravity of his action and aids in our suspension of disbelief. The cue begins with low ominous brass along with a sustained note in the high strings. This frequently used combination of high and low tessituras promotes tension, which is intensified as the strings initiate a tremolo sound, accompanying a low solo clarinet. The resulting stark and gloomy music provides an appropriate backdrop for McIntires actions, convincing us that he is doing something rather dangerous.

In addition to the connection between the Hessians motive and subsequent themes, there are other moments when we hear foreshadowing of Bernsteins later scores. For instance, at one point, during an Indian dance, the music is very like Fiesta from