T o all of my family and dearest friends, you know who you are, and especially to my loving parents, mum Sandra and dad Alec, my wifes family, big brother Mark and my wife Tara, a marvellous mammy in her own right to our beautiful children, Lexi and Charlie. Thank you for your patience, love and support while I worked on this book.

Sincere thanks goes to Rosie Virgo from John Blake Publishing for her faith in me as she approached me to write the book and her former colleague Sara Cywinski who suggested the book to her employers in the first place and offered me great encouragement and advice.

Warm thanks too to those who agreed to be interviewed for the book: Gerry Browne, Gay Byrne, Tommy Swarbrigg and Adele King, and to Gerry and my employers Independent News & Media for picture assistance. Special thanks must go to my brilliant book editor Rodney Burbeck for his invaluable skills as well as his patience and understanding with this being my first book. Hes been a great teacher.

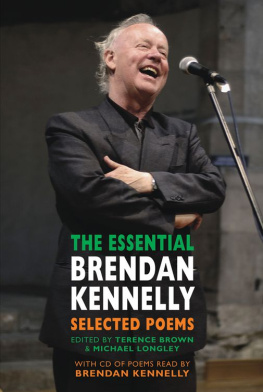

And finally to Brendan OCarroll, for though he does not know it unless he is reading this now, but he has been an unforeseen but incredible influence on my life. I hope I have done justice to his amazing life story and it proves to be an inspiration to others.

L ying in a pool of blood on a Dublin street, wounded after being shot, lies a young boy. He has only a slight pulse. Beside him, his father lies dead.

They were shot by British officers from the Black and Tans, World War One veteran British soldiers sent in 1920 to assist the Royal Irish Constabulary as the Irish War of Independence became a brutal and bloody affair. They were targeted because they were Republicans. Dragged from their family shop and frogmarched out onto the street, they were placed on their knees and the soldiers demanded information. When they refused, the officers cocked their rifles and pulled the triggers.

The shopkeeper was shot three times and killed instantly, while the little boy was hit once in the shoulder. His life was ebbing away, except the boy, just nine years old, didnt die. A journalist who came upon the scene saved his life by carrying him to the nearby Richmond Hospital. That young boy was Gerard OCarroll.

The next day, over breakfast, the journalist recounted the story to his family including his eight-year-old daughter Maureen. As fate would have it, Maureen grew up to fall in love with Gerard, the boy whose life her father saved, and they would have 11 children the last to arrive being a certain Brendan OCarroll.

Brendans grandfather Peter and his adult sons were in the Irish Republican Army which emerged after the Easter Rising. They were a different animal from the Provisional IRA paramilitary organisation that would wreak havoc from 1969 onwards in The Troubles, but nonetheless they were still an armed revolutionary military outfit.

Revealing the story of his dramatic family background to interviewer Barbara Bogaev on Washington radio programme Fresh Air on National Public Radio, when he was promoting his novels in the States in the spring of 1999, Brendan stressed that the old IRA were a kind of Republican army, and his grandfather would have been a covert operator a commando, for the want of a better word.

He owned a small store a kind of a drugstore, candy and cigarette store in Manor Street in Dublin. And although he was quite safe and his cover hadnt ever been blown, his three eldest sons, my fathers three eldest brothers, were active soldiers. They werent covert soldiers. And they were well-known.

This British contingent came around to the house at 7pm one evening and said, Look, we want to know where your three sons are. And what he would do is hed lead them into the store while he was putting on his boots, theyd help themselves to a pack of cigarettes or a couple of sticks of candy and then leave.

He was putting on his boots and they said, You know, were coming back tonight. And if you dont have the information where your sons are, well kill you. He took it with a grain of salt. And they arrived back at about 10pm and the three sons were upstairs. When they heard the banging on the door, the sons escaped onto the roof and started to make their way across the rooftops and to get out of the area.

My dad, who was nine at the time, he went down with his father. They didnt even give [my grandfather] a chance to put his boots on. He opened the door, and they said, Kneel down. And they put a gun to his head and they said, So where are three boys? And he said, I dont know. And if I knew, I wouldnt tell you.

And they said, Are you Sinn Fein? And he said, Born, and Ill die. And they said, Then die. And they shot him three times once in the head, once in the chest, and one in the stomach. And then they shot my father and left him for dead.

Brendan says he still has newspaper cuttings of the time, reporting the killings detailing how the soldiers pinned a notice to his shirt when he was lying on the ground that said, This man is a traitor to the Queen

Another press report, a treasured keepsake of his family history, told how his grandmother, who was upstairs, was afraid to come down. It is so illuminating, he says. It read Mrs OCarroll, fearful for her life, retired to her bedroom and betook herself to prayer. Isnt that lovely? Isnt that charming? You wouldnt see that in the press nowadays.

The circumstances of his fathers survival and marriage to the daughter of his rescuer, is an extraordinary twist of fate that determined the existence of one of the biggest showbiz stars Ireland has ever produced. But Brendans formidable mother, Maureen, who would become the first woman elected to the Irish parliament, also had fate to thank for her own existence.

Her parents were all set to elope to America and had tickets bought for the ill-fated Titanic, only for a change of plan at the eleventh hour. Brendan shared the remarkable tale during that same Washington radio station interview in 1999:

The story was that my mams mother made an announcement that she was about to marry a man who actually was older than her own father. She was 18 at the time, and this guy was 44. And her father wasnt having any of it. He said absolutely no way was he having any piece of this. So they decided in secret that they would elope. And my grandmother over a couple of weeks, little by little, snuck her clothes out of the house. And when she had them all ready and all out, she was ready to go away and go to America.

They were going to elope to America, which in that time, Im talking about early 1900s, eloping to America meant never coming home. There was no four-hour, five-hour flights home. So she sat up the night before she was to leave, and was quite upset about her father, who she was at this stage probably really fighting with.

The thought of saying goodbye to her mother the next day, with her mother thinking she was just going to work and never seeing her mother again, was very upsetting to her. While she was sitting up in the kitchen of the home, her mother came down and said, Are you OK? And she said, Yeah, Im OK.

So they made two cups of hot milk. And they sat there sipping hot milk. And in the middle of the conversation, my grandmother eventually told her mother what she doing, that she was eloping to America. Her mother said, Look, if your dad knew you were this serious, he would relent and you could have a proper marriage here in Ireland. So she convinced my grandmother to wake up her father, which she did.

And he threw the head. He went bananas. I mean, he went berserk, but then calmed down and agreed that rather than elope they should get married here in Ireland. My grandmother went around, told her boyfriend, who was delighted, and he went down to Heuston Station in Dublin that day to sell the tickets that hed bought for the elopement. The tickets were to get the train to Cobh in Ireland, at that time it was called Queenstown, to pick up the