Contents

Guide

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Green Dust: Irelands Unique Motor Racing History

Triumph of the Red Devil: The Irish Gordon Bennett Cup Race 1903

There Might be a Drop of Rain Yet: A Memoir

Parsons Bookshop: At the Heart of Bohemian Dublin, 19491989

Prodigals and Geniuses: The Writers and Artists of Dublins Baggotonia

City of Writers: The Lives and Homes of Dublin Authors

Princess of the Orient: A Romantic Odyssey

www.brendanlynchbooks.com

To the irrepressible Margie.

And to the memory of Alcock and Brown

and all the brave aviation pioneers.

Man must rise above the Earth to the top of the atmosphere and beyond for only thus will he fully understand the world in which he lives.

Socrates

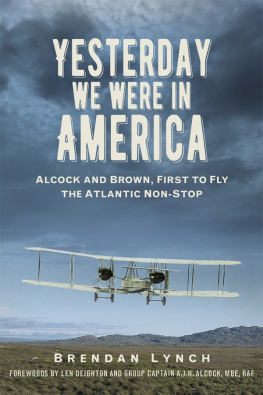

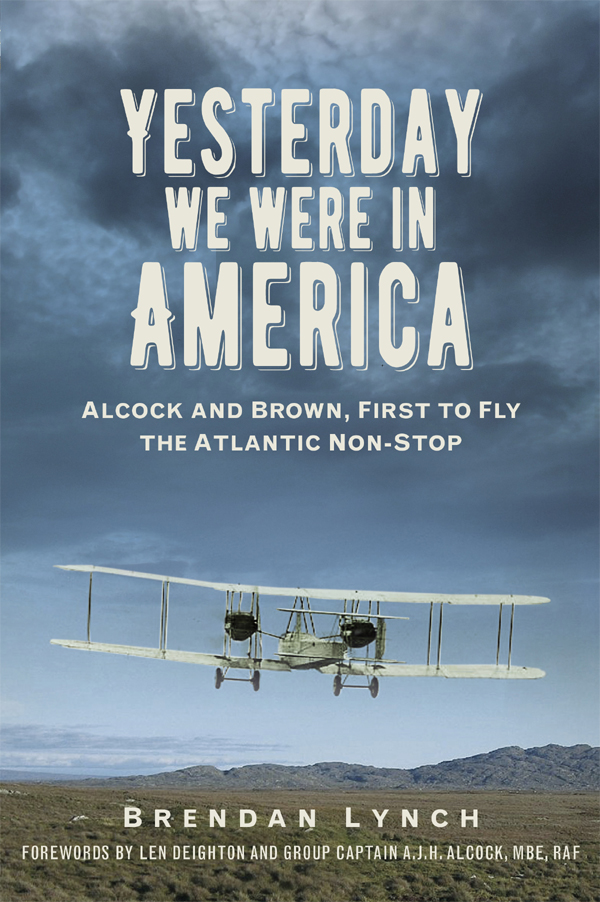

Cover Illustrations:Front: The Vimy takes off, next stop Europe. (Authors Collection) Back: A monument on Ballinaboy Hill points to the Vimys 1919 landing site. (Smb1001 via WikimediaCommons)

First published in 2012 by Haynes Publishing

This edition published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Brendan Lynch 2012, 2019

The right of Brendan Lynch to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9109 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Turkey by Imak

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

FOREWORD TO PREVIOUS EDITION

Wars are studied by historians because wars hasten progress, whether it is political, technical or social. This is particularly true of the First World War. Literacy and adult education for women and men, government supervision of industry and the conscription of workers and soldiers transformed Europe. The development of weapons also played a part in what became a worldwide conflict. In 1914 armies went to war with horses and swords. By 1918 warfare had been transformed by tanks, flame-throwers, radio sets, motor transport, poison gas and machine pistols not unlike those in use today. The fighting had transformed tactics, and made intellectual demands upon generals that very few could adequately meet.

Nothing changed more than aircraft. It had been the lightweight flying machines that won prizes at pre-war aviation gatherings. Frances single-seat Morane-Saulnier Type H monoplane with its 100hp engine had been the highlight of many air displays. By 1918 the strategic bomber was targeting German industrial towns.

By wars end the Vickers Vimy bombers, one of which John Alcock and Arthur Whitten Brown took across the Atlantic, had big and heavy Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines. By this time the rotary engine had become obsolete and the air-cooled engine had not yet demonstrated its true potential. So despite the added weight of the plumbing and the water needed for cooling, the Eagle with the Vickers airframe was probably the best combination available.

The Eagle owed its birth to the Mercedes engine. At the start of hostilities Rolls-Royce had taken it from a motor car on display in a showroom on Shaftesbury Avenue in Londons West End. The Rolls engineers examined it carefully and produced their V-12, which was rather like two Mercedes straight-six engines put together. But the Rolls engineers improved it. It had forged steel cylinders and Mercedes-style welded induction and exhaust ports. The overhead camshaft had two valves and two plugs for each cylinder. It had four Watford magnetos each supplying six cylinders, and four carburetors to distribute the fuel evenly. During the war the Eagle had been boosted from 225hp to over 360hp. This engine was used in flying boats, airships and bombers. It was a notable success story and brought Rolls-Royce a large proportion of its profits. The Vickers Vimy night bomber into which two Eagles were fitted had arrived just too late for operational service and everyone concerned with its production hoped to see it used for commercial aviation. An Atlantic crossing would bring exactly the sort of worldwide publicity that would promote the big aircraft into airline use.

However, Brendan Lynchs story is not just about machines. It is the story of two men. John Alcock, the 23-year-old pilot, was the younger of the two. He started flying before the war and by the time he joined the Royal Naval Air Service he had logged many hours and flown numerous aircraft of various types. On a bombing mission in 1917 he was shot down over Suvla Bay and became a prisoner of the Turks.

Arthur Whitten Brown was older and the more sober of the pair. He had served on the Somme as an infantry officer before becoming a Royal Flying Corps pilot. Shot down in France, the leg injuries he suffered in the crash (the British would not permit their pilots to use parachutes) permanently disabled him. His lame leg caused him to be repatriated from his POW camp before wars end. In Britain he worked on engine research for the Ministry of Munitions and then went to work for Vickers where, purely by chance, he met Alcock.

Both men knew the dangers and difficulties that the early aircraft brought, and both men had examined themselves and contemplated their future with the focus that imprisonment provides. And both men had given thought to transatlantic flight. It was a chance meeting but a perfect pairing: Alcock the bold, methodical, accomplished and very experienced pilot; and Brown, who was not only a dedicated navigator, but also functioned as what was later to be called the flight engineer. Browns mechanical knowledge was important at a time when engines in particular their fuel flow and temperature needed ceaseless attention.

The story of this historic flight has been shamefully neglected. It marked a moment when British aviation might have led the world. Alcock and Brown showed the way but the lesson was not learned. Britain, like other European powers, was content with low-performance engines on passenger aircraft that could do no better than short hops to South Africa and Australia; while in the 1930s American aircraft and airliners conquered both the Atlantic and the Pacific. Even in the 1950s Britains remarkable jet-engined Comet was forced to stop off at Gander, Newfoundland, because it could not make the full non-stop Atlantic crossing.

In these days of ruthless competition it is satisfying to record that Alcock and Brown were attractive and modest heroes who became close friends. They generously insisted that part of their monetary prize was distributed among Vickers support staff. Brendan Lynch, in this excellent book, tells their story with the skill of a dedicated researcher and the talent of a popular novelist.