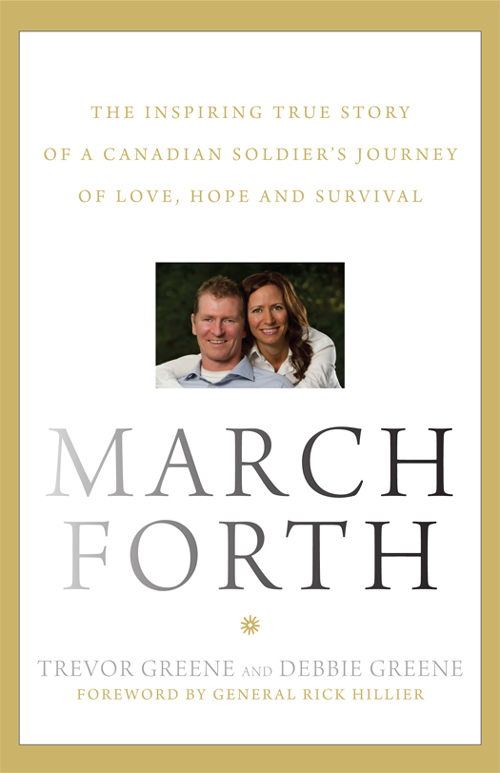

I knew much of Trevor and Debbies story early, starting with the savage attack on Trevor by a young and misguided man filled with such rage that he would abrogate Pashtunwali, the very code of behaviour that guides the young mans tribe so completely and guarantees the safety of guests. I had been briefed on the recovery process from the remote site of the attack and I followed, at a distance, Trevors evacuation from Shah Wali Kot to Kandahar Airfield to the U.S. Army Regional Medical Center in Landstuhl, Germany, and then, finally, home to Canada. Our medical specialists, including those involved in Trevors follow-up care, had walked me through the nature and extent of his terrible wound and the dire prognosis for any recovery beyond living incapacitated, essentially, unable to do much, if anything, in life as a man, son, husband and father.

What I did not know, however, was the kind of man that Trevor was and the kind of life partner that he had found in Debbie. It was only in meeting them personally, some long months after the attack, that I saw what sort of people they were and why their outcome would be different. Trevor was a beautiful, courageous man whose pale complexion and faint voice belied a drive and determination to recover that were quite literally out of this world. Debbie was a lioness, with courage and determination equal to if not greater than Trevors and a willingness to savage anything, or anyone, that would arbitrarily place limits on her man, her life partner. Clearly they were different.

Together, they were also unbeatable, and they created a story from the journey they travelled that inspires me and will, I am certain, inspire you. It inspires me to ignore the various daily complaints, whines and groans that come from those around us, despite the awesome society in which we, who have won the lotto that makes us Canadian, live. Trevor and Debbie inspire me to live life each and every day to the absolute fullest, to appreciate everything we have and to have with my wife the deep love that a man and woman can have for each other, with its capacity for enabling so much. They inspire me with what can only be described as a miracle of recovery. Trevor Greene and Debbie Greene, and their very lives, inspire me.

That inspiration came from a common thread that captivated me throughout Trevor and Debbies story. It is based on a most fundamental belief, one in which I myself believe: that of being part of something more and something bigger in life than ourselves as individuals. Trevor and Debbie believed in their responsibility to give more to others and to each other than they took, a belief that is evident in Trevors selection of the warrior path; in the support that Debbie provided to her partner by standing beside and behind him; in the courage Debbie and Trevor took from strong families and many friends; and in the couples belief in an inherently greater power with a plan for each of us. Their strong beliefs brought to mind a saying that originated in the Second World War: There are no atheists in foxholes. The fundamentals that keep men and women sane, strong and focused, with an ability to carry on despite incredible fears and difficulties, are not always obvious in the lives that most of us live but are easily visible during times of fear and instability. Such is what marks both Debbie and Trevor in this most compelling of life stories. They, in their foxhole, continued to believe what most others had long since given up, and they worked to make their belief a reality. There are lessons in how they did this for all of us.

It was Trevors strong beliefs that brought him to Afghanistan. Living life to the fullest, appreciating each day, loving his friends and family and wanting to give (and give back) to others led Trevor after many years to push for a deployment into Afghanistan as a CIMIC (Civil-Military Co-operation) officer. Trevor was offered the position, and in early 2006, he joined the first Canadian battle group to return to southern Afghanistan. Connecting the hard military work with the rebuilding effort became part of his everyday routine until the attack. Surviving and returning home, he was all but dismissed by a medical and military system that assumed his grievous wounds were too much for anyone. Yet recover to an unbelievable extent he did, with Debbie pushing, pulling, encouraging, praying, sustaining and, yes, crying with him through the pain, setbacks, stifling bureaucracy, impersonal caregivers and every other challenge imaginable. Every Canadian would benefit from reading this life story, comparing his or her approach to life with that of Debbie and Trevor, and becoming inspired by what Debbie and Trevor have done and continue to do. Every Canadian would live life more completely as a result. God bless two great Canadians every day.

A baleful desert sun screamed down mercilessly on my helmet while the heat and dust wrapped around me like a monstrous, suffocating pillow. Through the sodden kaffiyeh desert scarf wrapped around my mouth and neck, the air was malodorous with the acrid stench of smoke and the burned-paper smell of ancient dust. Behind my sunglasses, my eyes blurred from the oily sweat oozing from my forehead. My saliva thickened, and dust coated my parched throat. My rifle was cumbersome and warm in my shooting gloves. The bottoms of my feet burned in my tan desert boots as I carefully stepped around ankle-breaking rocks of crumbling shale. We were on the third dusty day of foot patrol.

I was attached to One Platoon, Alpha Company, 1st Battalion PPCLI. Call sign Orion 11. Our mission was to patrol a five-hundred-square-kilometre area of operations in the foothills of the Hindu Kush, bounded in the east by a circle of jagged mountains we called the Belly Button. No foreign army had been in the Belly Button, the most dangerous real estate in Kandahar Province, since the fall of the Taliban in 2002.

The Red Devil Inn, so called for the Alpha Company nickname, was a wattled mud compound that had been converted into our forward operating base. Our home away from home was about seventy kilometres as the buzzard flies from the main coalition base at Kandahar Airfield but closer to a hundred after dusty swerves and switchbacks. The compound was the size of an elementary school gymnasium and was just outside the village of Gonbad, about seventy kilometres north of Kandahar Cityright in the heart of Taliban country. A road led from the Red Devil Inn through the village and branched to the south. This branch came to be known as IED Alley because of the countless bombs that had been laced into the road by the Taliban.

The front entrance to the compound was a massive double-doored gate. A small hill in front of the gate was always crowded with villagers mesmerized by our vehicles. They were insatiably curious and would hang out on the hill for hours, seemingly in shifts. We wanted to maintain goodwill with the locals by being good neighbours, but their proximity to the Inn was of concern. Every morning, the villagers were frisked by three Afghan National Army (ANA) soldiers in the unlikely event they carried weapons or explosives.