Text: Gerry Souter

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

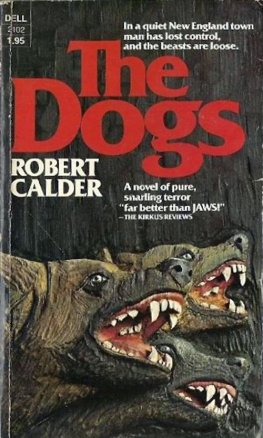

Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78160-621-6

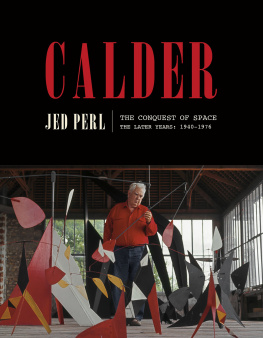

Alexander

Calder

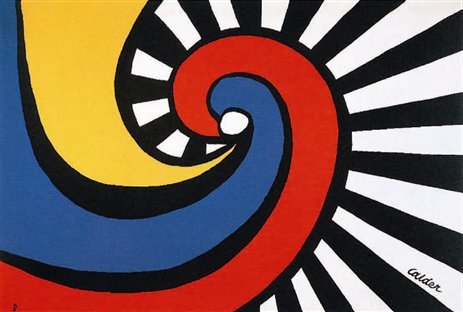

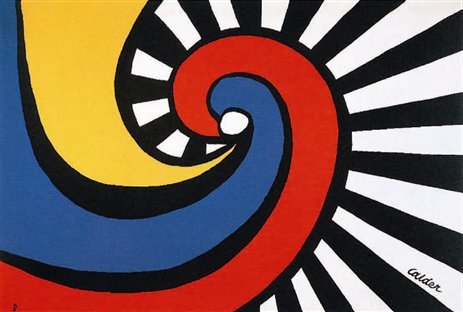

Spirales, not dated.

Aubusson tapestry, 168 x 242.9 cm.

Jane Kahan Gallery, New York.

Art in Flight

Alexander Calder was a big man, but light-footed; he had big hands, but the facile fingers of a surgeon; he possessed the concentration of a monk, but loved to party with friends. He was a genius, but not a bore, and he left a giant hole in many lives when he died in 1976. The roaring laugh is stilled and no more sculpture comes from those hands that were rarely still, but he left behind his sense of awe and joy in thousands of wire windings, pirouetting shards and sheets of striding steel. And, as long as there is a breath of air and the sun rises and sets, revealing and shadowing our world, the sculpture of Alexander Calder changes its aspect and shows us something new.

He was born into a household of artists in Lawnton, Pennsylvania, just outside Philadelphia, on July 22, 1898. As for career options, he never stood much of a chance. He became the third Alexander of an artistic trinity formed by his grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder, and his father, Alexander Stirling Calder, both sculptors of note in their time. His mother, Nanette Lederer, painted portraits. Much of his early childhood seems to have been spent shuttling back and forth between his fathers and mothers studios. His fathers workplace was above an old livery stable that smelled of horse droppings, wet clay and damp wood, where Stirling Calder stared at him from behind a sodden mound of mud. Shivering, the younger Calder watched his fathers nimble fingers extract his likeness from the lump except for his goose pimples and the scrape on his knee. At his mothers studio with its paint-smeared rags, jars of turpentine and linseed oil, young Alexander watched her charcoal-stained fingers sketch his likeness. He received twenty-five cents for every boring two-hour session.

Possibly due to the proliferation of Alexanders, his father was Stirling and he himself came to be called Sandy by the family. The youngest Calder shared their attention with a sister, Peggy, two years his senior, who had been born in Paris, a fact he often envied. Because of his fathers calling and his ill health, this household changed addresses many times between 1905 and 1909.

As they criss-crossed the U.S., following Stirling Calders sculpture commissions, young Sandy tried to duck the family occupation, as most kids do when they seek their own identities. Instead of art school, he enrolled at the Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, emerging in 1919 with a mechanical engineering degree. This love of mechanics came from his childhood creation of toys built from any material that came to hand. In 1929, he wrote, I spent my childhood as a boy in the midst of my family, always enthusiastic about toys and string, and always a magpie collector of bits of wire and all the prettiest stuff in the garbage can. When I was a kid of eight my father and mother gave me some tools

Calders Circus, 1926-1930.

Mixed material,

137.2 x 239.4 x 239.4 cm.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

As his family moved from one commission location to another, in his idle moments Master Calder managed to produce his earliest surviving experiments in sculpture, A Duck and a Dog, both made by folding and cutting single sheets of brass, origami-like, into three-dimensional critters. At that age, Calder had embraced the artistic concept of thinking ahead; handling whatever material was at hand to create elements that, ultimately, must work with other elements to produce a pre-visualised result. The small menagerie proved to be portentous.

Having earned his engineering degree, he embarked on a series of jobs as far from fine art as they were bone-grindingly dull. From automotive engineer to claims adjuster and garden cultivator demonstrator, he wandered through five states as a book-keeper, staff member of The Lumber Journal and a map colourer for a hydraulic engineer. In virtually all these jobs, his inability to fit in with the status quo sent him out of the door. He finally gave in, threw up his hands and submitted to his parents way of life, shunning the world of steady work to become a bohemian iconoclast artist.

After trying some courses in drawing nude figures, he lost patience and got his seamans ticket as a stoker in a ships engine room. In 1922 he worked his way from New York to San Francisco in the boiler room of the oil-fired Pacific Steamship Companys high-speed passenger liner, H. F. Alexander . The trip exposed his creative sensibilities to some dazzling scenes, including an early morning vision of the rising sun and the setting moon, two brilliant globes on a knife-edge horizon in a cloudless sky. These images inspired him to take up painting.

On returning to New York in 1923 at the age of 25, Calder enrolled at the Art Students League and studied under the likes of Thomas Hart Benton, John Sloan and the highly stylised illustrator Guy Pene du Boise. By 1924 Calders parents had headed for Europe, leaving Sandy to set up shop in his fathers former studio. His income came from a job as illustrator for the racy tabloid of its day, The National Police Gazette . He managed to snare a ticket good for two weeks free admission to the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circus. Calder went every day, making sketches from every possible viewpoint. He became fascinated by the movement, colour and rigging of the acts. From high in the back rows of seats, the chaos and pantomime appeared to be a loosely linked colony of brightly-lit toys. The impression that he took away would change his life forever.

Throughout 1924 and 1925, Calder was a creative gadfly, etching, sketching, oil painting, and creating his first wire sculpture, a sundial in the form of a rooster. He also whittled his first wood sculpture from a fence post and illustrated a book. His oil painting, The Flying Trapeze , survives, demonstrating his eye for movement and dramatic shapes. The safety net and sweeping railings, punctuated by the faces of the audience, add considerable dynamics to the composition that surrounds the spotlighted aerialists.

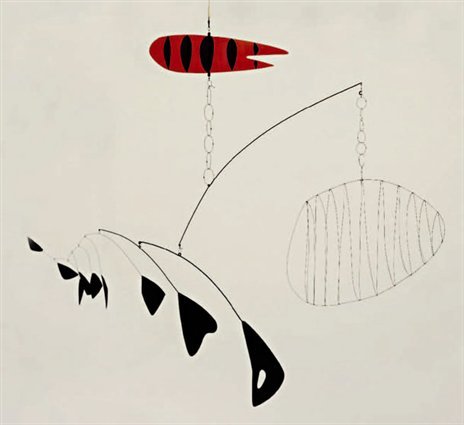

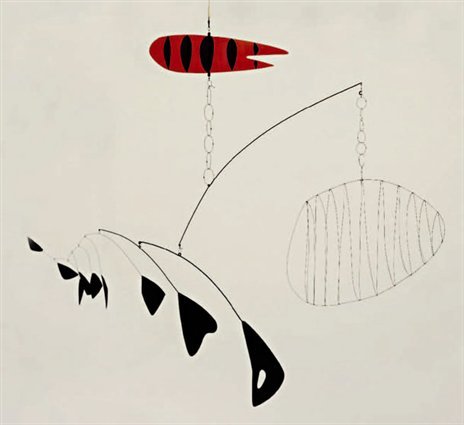

Lobster Trap and Fish Tail, 1939.

Sheet metal, wire and paint,

Next page