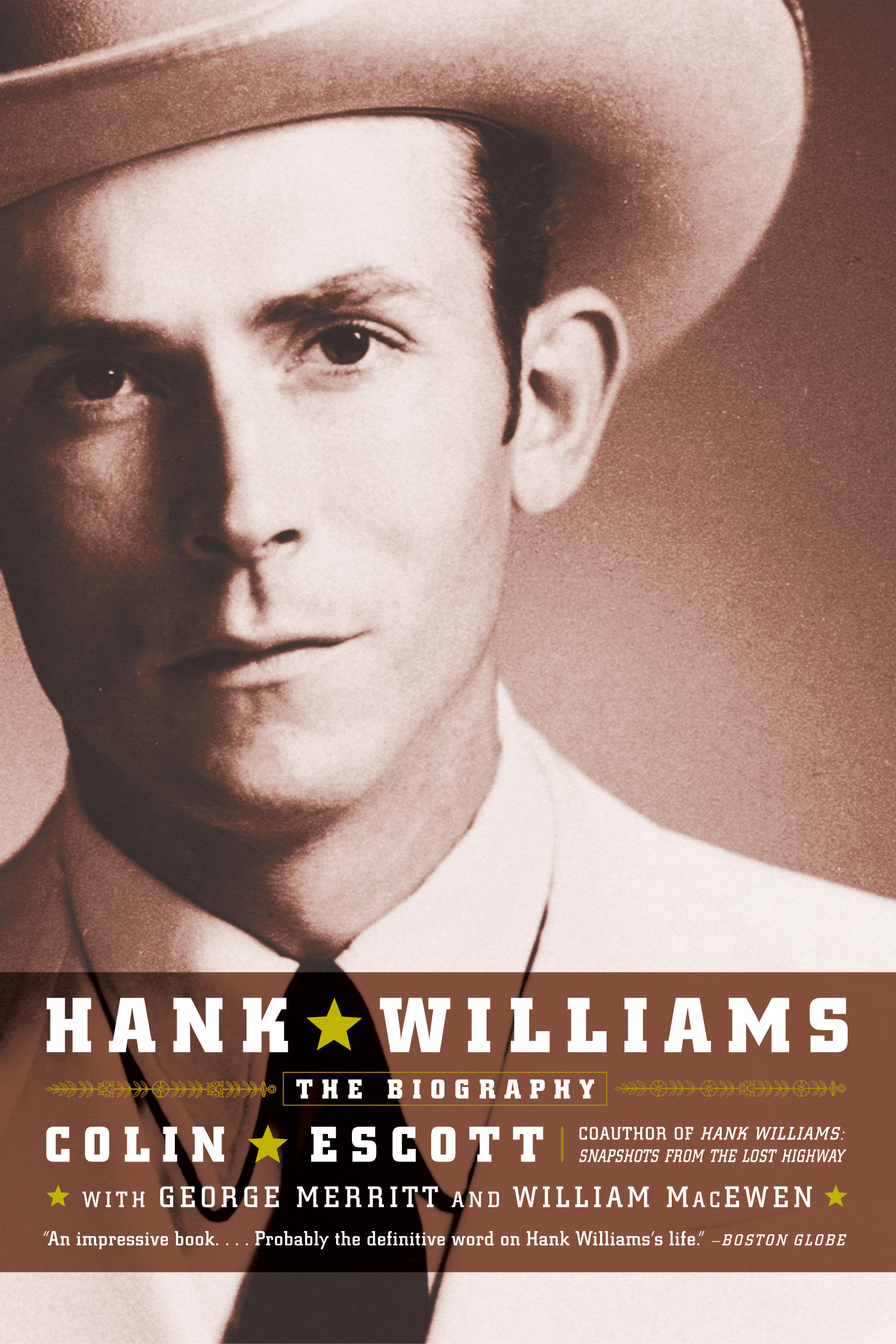

Copyright 2004 by Colin Escott

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

First eBook Edition: April 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-07463-6

Also by Colin Escott

Hank Williams: Snapshots from the Lost Highway, with Kira Florita

Good Rockin Tonight: Sun Records and the Birth of Rock n Roll, with Martin Hawkins

Tattooed on Their Tongues

Lost Highway: The True Story of Country Music

Roadkill on the Three-Chord Highway

TO A HILLBILLY SINGER DYING YOUNG

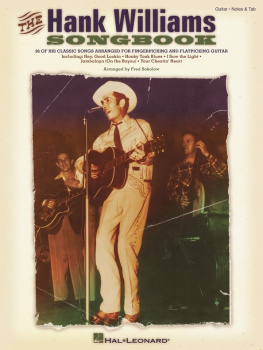

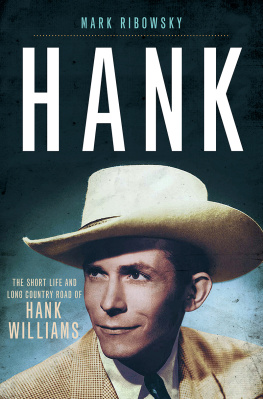

H ANK Williams has been dead for fifty years. In fact, it was fifty years ago the night of this writing that he began his last journey. Knowing all that we now know about the precise route, its tempting to look at the clock and imagine where he was. Its equally tempting to wonder if he knew where he was. Midnight struck for Hank Williams somewhere on that last eerie road trip. But where? Born in the oppressive heat and humidity of south Alabama, he almost certainly died with snow in his headlights.

Ten years ago, I was finishing the first edition of this book. I clearly remember working on New Years Eve 1992, having much the same thoughts as I have now. Where was he forty years ago tonight? If asked, I wouldnt have bet on too much new information turning up between the fortieth and fiftieth anniversaries of his death. Perhaps a couple of interviewees whod eluded us would emerge; perhaps one or two whod avoided us would cooperate; perhaps a few recordings would turn up. I thought our little book would otherwise stand unchallenged and unchanged. But I was wrong. Several of Hanks former bandmembers, long thought lost, have indeed come forward. Many new recordings have been uncovered. Hanks sister, Irene, died, leaving a trove of photos, papers, and memorabilia that no one knew she possessed. Another trove of legal correspondence has surfaced, and beneath the lawyers dry concision theres a sense of the bitter conflict that drove one legal action after another, year upon year. Crucial information has emerged on the blues musician, Tee-Tot, who taught Hank. Even more information has surfaced on the long car ride during which Hank died and the bogus doctor who treated Hank with such disastrous results over his last weeks.

As early as New Years Day 1953, Hank Williams became an object. Parties wrestled over him, not only as if he wasnt there (which, of course, he wasnt), but as if hed never been there. He was like an antique to which several family members laid claim. Yet the reason that the legal actions continue year after year is that the small body of work left to us grows in importance. Every year, several hundred thousand people buy a Hank Williams CD. Surely longtime fans arent buying these records. Thanks to the record companies, longtime fans have every hit several times over. Those several hundred thousand new sales must, for the greater part, represent a new audience discovering the truths that we discovered all those years ago. It seems as though the sterner stuff survives. Both Frank Sinatra and Perry Como sold millions of records, yet its Sinatras dark soliloquies that have lasted while Comos records remain trapped in their place and time. Bruce Springsteens bleakly minimalist Nebraska dismayed the stadium rock crowd on release in 1982, but now sounds better with every passing year. The fierce, insurgent music of Hank Williams still reaches us in a way that the cheerier music of Eddy Arnold and Red Foley does not. Yet, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Arnold and Foley comfortably outsold Hank Williams.

Hank Williams had the great fortune to come and go at exactly the right time. Most of his contemporaries lived long enough to make some very bad records; Hank didnt. Most of his contemporaries had to come to terms first with rock n roll, then with the Nashville Sound; Hank didnt. Several of his contemporaries found themselves hawking remakes of their greatest hits on cable television; Hank didnt. Death is a good career move if it can be timed right, and no one ever timed it better than Hank Williams. In terms of forging a legend, he could have done no better than burn out at twenty-nine before his fire grew dim and the face of country music changed. His death left what is still the most important body of work in country music; in fact, one of the defining caches of American music. It also left the tantalizing promise of what might have been.

Perhaps the next ten years will see as much new information emerge as has emerged in the last ten years, but thats no reason to hold off this revision. For a few weeks in 1994, we flattered ourselves into believing that our old work was definitive. Thats no longer the case. Enough new information has surfaced to warrant a complete rewrite, and so many new photos have been found that Kira Florita and I coproduced a photoessay, Hank Williams: Snapshots from the Lost Highway (DaCapo Press, 2001), which serves as a companion piece to this work.

Thinking about Hank Williams, I return endlessly to a poem I learned back in England when I was a child, A. E. Housmans To an Athlete Dying Young. Housman says much that Ive struggled to say when called upon to explain the iconic power of Hank Williams. Here it is, in part.

Smart lad, to slip betimes away

From fields where glory does not stay

And early though the laurel grows

It withers quicker than the rose.

Eyes the shady night has shut

Cannot see the record cut,

And silence sounds no worse than cheers

After earth has stopped the ears;

Now you will not swell the rout

Of lads that wore their honours out,

Runners whom renown outran

And the name died before the man.

Colin Escott

New Years Eve 2002

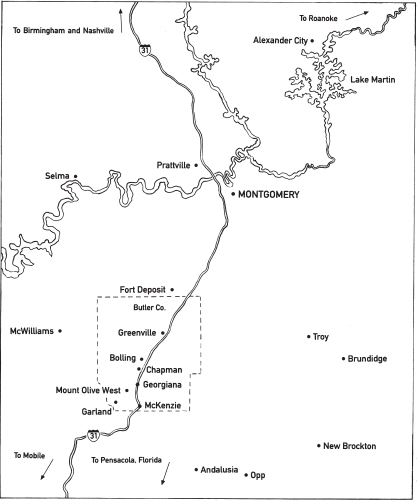

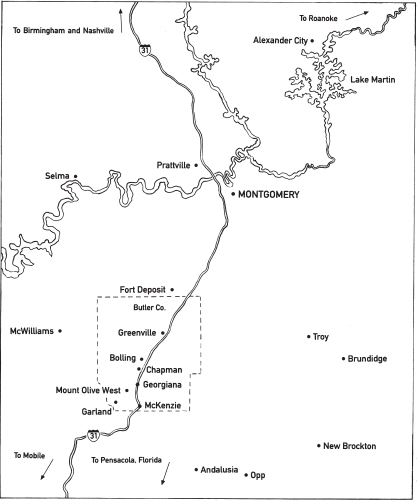

South Central Alabama

Map by Lindsay Grater

The road to that bright happy region Is narrow and twisted, they say But the broad one that leads to perdition Is posted and blazed all the way.

The Drifting Cowboys Dream (unknown)

THE DRIFTING COWBOYS DREAM

T HE Mount of Olives, which overlooks Jerusalem from the east, will, according to the Book of Matthew, be the gathering place when the dead rise upon the Messiahs return. Those buried on the Mount will be the first to rise, and will have pride of place at the Messiahs side. As a child, Hank Williams would not go to sleep unless a Bible lay beside him in bed, so he inevitably learned about the Mount of Olives, but had he returned to his birthplace in Mount Olive, Alabama, he would have seen a red-dirt settlement of half a dozen houses strung desultorily along an unpaved road. Not even a crossroads. The few souls that resided there eked out a living as farmers or as indentured employees of the lumber companies opening up the dark, coniferous forests of south Alabama.

Hank was the third and last child of Elonzo Lon Huble Williams and his wife Jessie Lillybelle Lilly Skipper Williams. Their first child was alive at birth but died soon after; its unknown if he or she was even named. Lon and Lillys second child, Irene, was born on August 8, 1922; Hank followed on September 17, 1923. According to Lon, Hank was to be christened Hiram, after King Hiram of Tyre in the Book of Kings, but when he was belatedly registered with the Bureau of Vital Statistics at the age of ten, it was as Hiriam. Friends, family, and neighbors called the boy Harm or Skeets. He was born at home in a double-pen log house known as the Kendrick Place because it had been built in the late 1800s by Mr. Wiley Kendrick and his wife, Fanny. Lon proudly told Hanks first biographer, Roger Williams, that he paid thirty-five dollars to have a doctor in attendance, and had enough money set aside to hire a black nanny.