Contents

Copyright 2017 by Cecelia Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this story may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Books from Meath Press and Oghma Creative Media may be purchased educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail the Admin Department at .

ISBN: 978-1-63373-254-4

E-Book Formatting by Casey W. Cowan

Editing by Michael L. Frizell

Meath Press

Oghma Creative Media

Bentonville, Arkansas

www.oghmacreative.com

To my three great loves:

Dennis, Cody, and Cheyenne

and

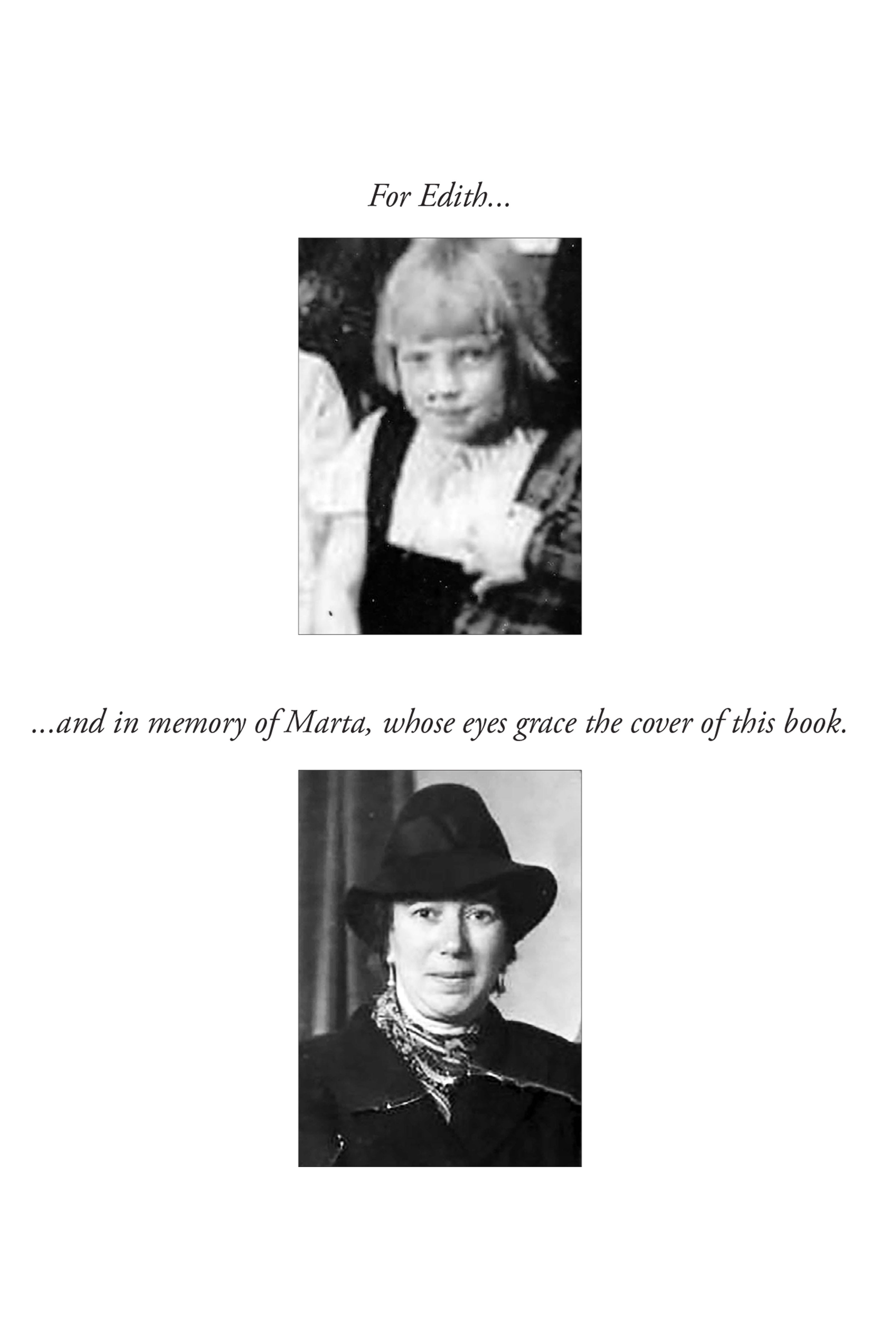

to Edith,

Thank you for long talks, laughter,

Dr. Peppers, and popcorn

Part I

but the donkey, seeing that no good wind was blowing,

ran away and set out on the road to Bremen.

The Town Musicians of Bremen, The Brothers Grimm

End of the Road

May 1945

Karl-Heinz and I became true partners in crime that day.

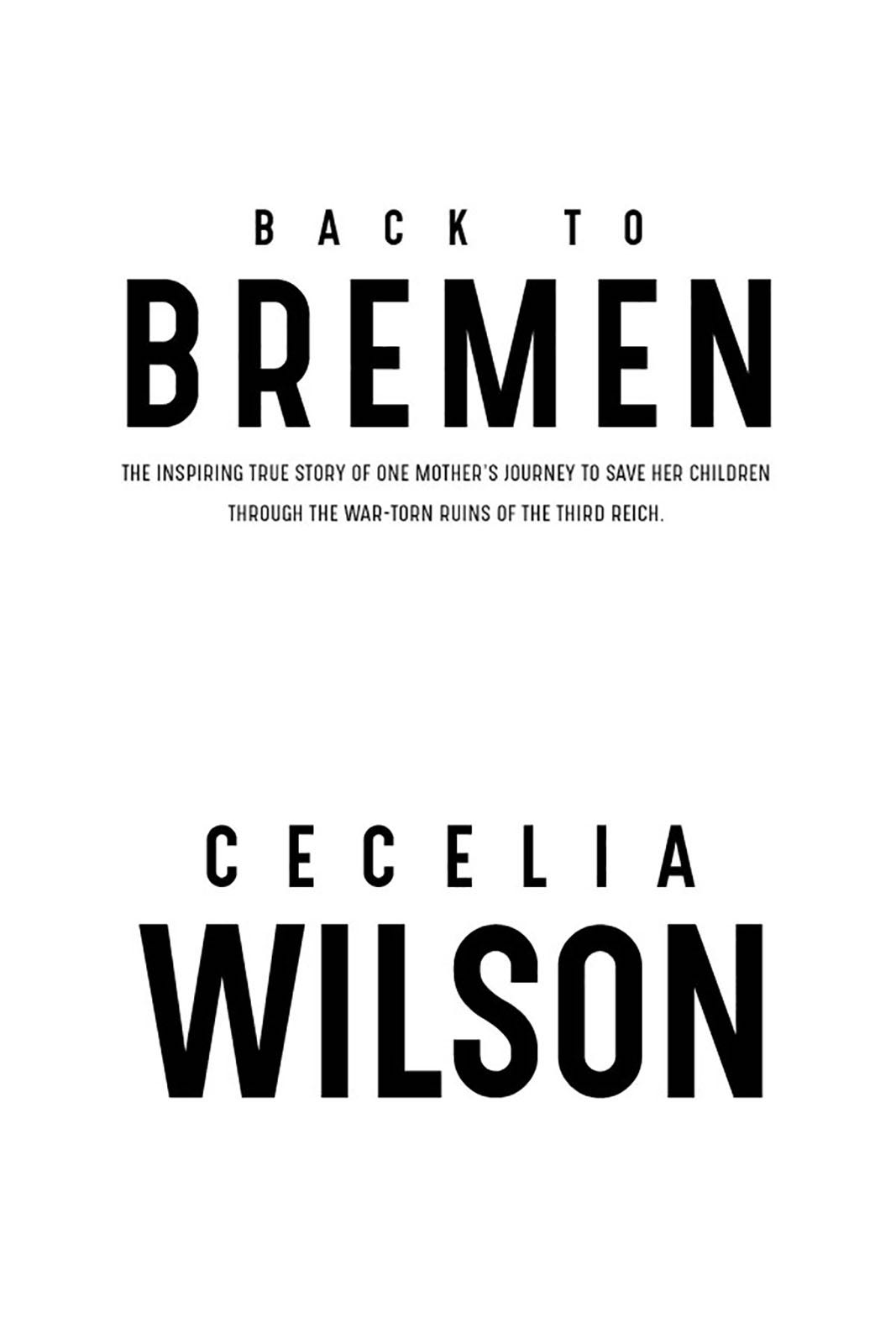

I was nine, Karl-Heinz had just turned twelve, and we were both old enough to know we would be in trouble. Marta Rpke was not a large woman and she had never been the disciplinarian in our family, but the war had forged in our mother a steely resolve to see that her family was kept intact. She had preached always stay together to all of us so often that it was imprinted in our minds. And keeping seven children together during the length of the war without the help of my oldest brother, Gnter, and my father, Diedrech, had been quite a task.

Much of the village we entered had recently sustained heavy damage, but the shops that had been able to withstand the worst of the bombings were open for business, providing services and sparse goods to the locals, and accepting almost any form of payment offered.

Edith! my brother whispered as loudly as possible to get my attention. He cut his eyes toward the small shop up the street from where we stood.

I nodded. He didnt have to say anything more; my nose told me all I needed to know. We had just located a bakery, and as the scent of warm bread floated on the morning breeze toward us, my mouth watered. For two German children who had eaten nothing but stolen vegetables for weeks, we were desperate to taste what had been tempting our senses and making our empty stomachs groan all morning.

The Second World War had ended in Europe and Hitler was dead. But, we could not feel relief. Germany was in shambles and our only thought was returning home to Bremen in the northwest. For two months we hiked with Frau Meier, her son, and two German soldiers from eastern Germany after escaping from the Soviets. We were now somewhere in British-occupied western Germany, but the road seemed to stretch to infinity.

And while the twelve of us had walked together for hundreds of miles, we were hardly alone. Every day, we were surrounded by thousands of souls who, like us, were just trying to get home, yet none us were sure what we would find when we reached our destinations. The longer we walked, the more the refugees seemed to increase exponentially, and the seemingly endless sea of humanity appeared dazed, shocked, and bitterly tired of the war that had brought so much death and destruction.

There was no doubt the crowds included criminals, spies, and Nazi officers trying to avoid detection, and Mother warned us of those dangers often. Despite knowing the repercussions we would endure once our mother saw us again, hunger drove us closer to the open doors of the bakery that was now only steps away.

My heart beat loudly as we approached the front of the shop. Through the window I could see breads and pastries, and I thought I might reel at the sight. I could also see my reflection and was mortified. I hadnt seen myself for almost two months, and I winced, wishing I could forget the image. None of us had bathed, washed our clothes, brushed our teeth, or combed our hair. I have no doubt we smelled terrible. My shoes were in poor condition: they remained either soaked from rain, or dried and cracked from wear and tear. My feet ached from trudging through fields, up hills and across dirt and gravel. The filthy, tattered clothes I wore were all I owned now and they literally hung off of my increasingly shrinking frame. But that was no surprise; we never knew when or from where our next meal would come. We had sipped water from streams we spied along the way or, after a rain shower, we even resorted to finding puddles in order to quench our thirst. And none of us had eaten anything beyond what little we could find near roads or in pastures.

I felt sorry for the farmers whose properties we had passed through. Their hard labor suffered from all the foot traffic in those months at the end of the war. Like us, many people avoided the more-traveled roads to get home. Like thousands of others near starvation, we were driven to steal cabbage, potatoes, and any other vegetables or fruits we could find in tilled ground and orchards. When a garden was spotted, there would be a rush of people digging up what could be found before the owner spotted us. Grabbing a carrot, we would break off the green tops and use the leafy stems as brushes to clean off as much dirt as possible from our stolen entre before eating it raw.

Famished and exhausted, we woke in the wooded countryside to the intoxicating aroma of homemade bread floating from the villages center. Slipping away from our mothers ever-watchful eye, Karl-Heinz and I had stealthily followed the scent until we had located the bakery.

Knowing we looked like vagabonds, I was hesitant to enter the shop, but Karl-Heinz elbowed me in the side and we stumbled through the entry at the same time. Inside, was an elderly man on the other side of a counter, waiting on patrons willing to buy or barter for his baked goods. We made a feeble attempt to blend in, pretending to nonchalantly peer at the food on display on the shelves inside the glass counter, but it was painfully obvious we were without ration cards or Reich marks and everyone in that shop knew it. No doubt, the man was watching the two wretched-looking children in his shop, suspicious of our motives as we loitered behind his legitimate customers.

I glanced over at Karl-Heinz and realized he was not focused on what was inside the counter, but what was displayed on the counter: several long, plump loaves of golden brown bread stacked one atop the other. He didnt have to look at me to communicate his thoughts. It was if his eyes had tracers telegraphing his objective. The only question now was when the timing was right to follow through on the plan.

There was a hausfrau speaking to the elderly baker, and though I could see her mouth forming the words, all I could hear was my own heavy breathing. I swallowed and was sure the seven or eight men and women in the shop could hear the sound as it traveled down my throat. My parents would be mortified. They had not raised any of us to steal, but here my brother and I stood, contemplating just that. I looked up and was sure my thoughts were being read. I noticed the baker was torn between watching us and focusing on the hausfraus requests. She pointed to some item she wanted on a lower shelf and as the old baker leaned over to pick it up, Karl-Heinz made his move, snatching three loaves of bread in quick order, elbowing his way through the startled patrons, and sprinting for the door. I followed suit, grabbing a pair of loaves and running like mad in my brothers wake.