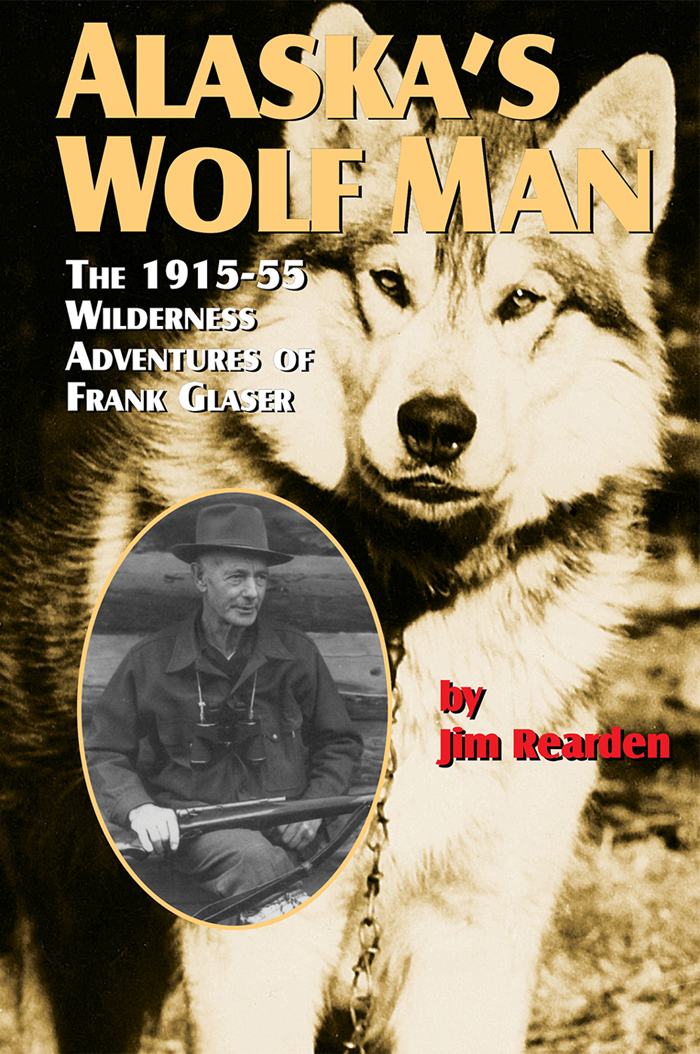

Alaskas Wolf Man

FRANK GLASERS ALASKA

Alaskas Wolf Man

The 191555 Wilderness Adventures

of Frank Glaser

by JIM REARDEN

Copyright 1998 by Jim Rearden

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher.

The print edition is available from

Pictorial Histories Publishing Company, Inc.

pictorialhistoriespublishing.com

Library of Congress

Catalog Card Number 98-66445

ISBN 978-1-57510-047-0

ISBN (e-book) 978-0-88240-935-1

Cover Graphics Mike Egeler

Typography, Map & Book Design Arrow Graphics

Published by Alaska Northwest Books

An imprint of

P.O. Box 56118

Portland, Oregon 97238-6118

503-254-5591

www.graphicartsbooks.com

Contents

Foreword

In 1940, when a letter arrived at Fairbanks, Alaska, addressed to The Wolf Man, it was promptly delivered to Frank Glaser, a wolf hunter (officially, Predator Control Agent) for the federal government.

Frank Glaser possessed encyclopedic knowledge of Alaskas wolves and other wildlife; he was also an expert at living in Alaskas wilderness. From 1915 to 1955 he led an adventurous life in Alaska as a market hunter, roadhouse operator, dog team freighter, big game guide, collector of wildlife specimens for the federal government, trapper, explorer, breeder of wolf-dogs, and federal wolf hunter.

Glasers views on wildlife were those of the late 19th and early 20th centuries when hunting and hunters were respected as an important segment of society. During his time a primary goal of wildlife conservation was to eliminate predators, and the Territory of Alaska as well as most states paid bounties for the killing of bad wild animals in the belief that this would benefit good wildlife.

Glaser was fascinated by all wild animals, but he was especially drawn to the wolf. When wolves became abundant near his Savage River trapping cabin in the Alaska Range after the mid-1920s he had an opportunity afforded a privileged fewthat of daily observing good numbers of wild wolves. For more than a decade as wolf howls resounded among the mountains and tundra flats around his lonely cabin, he watched the big predators hunt and kill, mate and raise young, fight, and kill and eat one another. Several captive wolves he kept also contributed to his knowledge, as did the wolf-dogs he bred. He admired wolves for their intelligence and skill as hunters. At the same time he was determined to kill as many of them as he could to protect caribou, moose, and wild sheep.

Comments of his associates give some insight into Frank Glaser, the man, the woodsman, the companion, the hunter, the trapper:

Sam O. White, himself a top woodsman, once told me, Frank Glaser was a loner. He much preferred to be in the woods and out on his own. He was one of the most skilled and toughest woods-men in Alaska. He was tireless on the trail.

For many years White was a wildlife agent for the Bureau of Biological Survey in Alaska. For several years he and Glaser worked together for the Survey and its successive agency, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS).

Glaser was an expert on extended trips through the wilderness, and always knew where he was. He knew how to use every little advantage the terrain or foliage offered. Frank was never at a loss in the woods; he was as much at home there as a wild animal. He was an expert at finding edible roots and bulbs and other plants to supplement his diet. He was also good with a soup bone, said White.

White added, I searched for one of his camps once in a clump of spruce timber, and although I knew pretty well where it was I was hard put to find it. Another of his skills was being able to call just about any animal in the woods.

He could gain the confidence of captured animals very quickly. He trapped a huge black wolf on Goldstream [near Fairbanks] one winter. That wolf had a head as big as a bearsone of the biggest wolves Ive ever seen. Frank kept him in an old cabin on a chain and he would walk nonchalantly into the cabin with water and food for the animal. While the wolf was mostly sullen, he never offered to attack. I wouldnt have ventured into that cabin unless that wolf had been trussed in chains, claimed Sam.

Frank killed a lot of wildlife, but he used it all. He was a natural conservationist. He did not ordinarily kill for sport only for food and clothing. Even when it made no difference legally he always killed bulls rather than cow moose or caribou; the same with sheephe shot rams, not ewes, said White.

Dr. Wilson L. Du Comb of Carlyle, Illinois, engaged Glaser as a hunting guide in September, 1935. In 1978, Du Comb wrote me, We were both young men then, I was 34 and Frank was in his early forties. I slept in the cabin on Savage River that Frank built alone in ten days. Sod roof and dirt floor, but with a good stove and plenty of firewood it was very comfortable. It was with Frank that I killed my first grizzly, in fact my first bear of any kind. I cannot praise him too highly. Frank Glaser was a gentleman, an excellent guide and a fine companion.

Oscar H. Vogel, trapper, guide, premier outdoorsman and long-time Alaskan, met Glaser in 1934. He told me, During the years from about 1930 to 1940 when wolves were ravishing Alaska, Frank was wolfing the whole northern part of the Alaska Range east of McKinley Park. He worked the year around getting rid of wolves, digging dens in the spring, trapping and snaring in winter. At the same time I was trapping, shooting, and snaring wolves in the Talkeetnas.

Frank knew wolves just about from A to Zed, living with them year in and out. He was well established when I was only beginning and he gave me many valuable tips on trapping, every one of which proved effective, said Vogel.

Dr. Neil W. Hosley, a FWS employee and one-time Leader of the Alaska Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks, and later the Dean of that university, made field trips with Glaser in the late 1940s and early 1950s. He told me, Frank Glaser was a careful observer and his stock of information, particularly on wolves, led to his employment as a Predator Control Agent of the FWS. He worked with Adolph Murie during the studies which led to Muries classic book The Wolves of Mount McKinley, and Murie included Glasers observations in the volume.

Hosley, referring to Glasers years as a government wolf hunter, said, Franks first three days in the office after a field trip were at least tolerable to him since reports had to be written. But then he got itchy to get out in the boondocks again. In midwinter with deep snow and temperatures well below zero, he would decide that the wolves somewhere, perhaps in the Alaska Range, needed control. A pilot with a ski-equipped plane would set him down at the selected place with his pack, rifle and snowshoes. Then for a week or so, he was alone in his element and happy.