Published by Black Inc.,

an imprint of Schwartz Publishing Pty Ltd

3739 Langridge Street

Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia

email:

www.blackincbooks.com

Copyright Joel Meares 2015

Joel Meares asserts his right to be known as the author of this work.

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior consent of the publishers.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Meares, Joel, author.

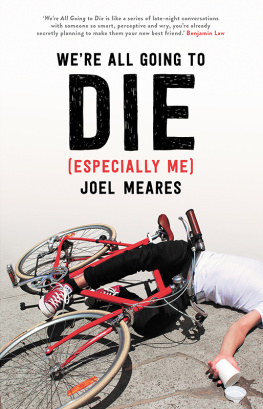

Were all going to die (especially me) / Joel Meares.

9781863957243 (paperback)

9781925203059 (ebook)

Generation Y--Attitudes.

Generation Y--Social life and customs.

Australian wit and humor.

305.2

Cover and text design by Peter Long

Author photograph by Daniel Boud

WERE ALL GOING TO DIE (ESPECIALLY ME)

I was twenty-eight when I first realised I was going to die, and I have a member of the 1988 British Olympic wrestling team to thank for letting me know.

Dr Martin Doyle who, unfortunately, did not place at the Seoul games is my physiotherapist. He works in Pyrmont, in Sydney, where he owns a practice made up of several small rooms equipped with machines that make your lower back vibrate deliciously and a gym that he has decorated with pictures of himself back in his freestyle-wrestling glory days. (He doesnt look all that different today, really: compact, wiry, just a little more salt and pepper on top.)

I started seeing Dr Doyle when the groan in my lower back that Id been hearing since my teens turned into a constant roar. During our first consultation, he nodded knowingly as I told him that I had a desk job and spent my leisure hours watching movies and reading books and decidedly not hiking in the Blue Mountains or cycling to Wollongong. Then he asked me to lie facedown so he could get the lay of the land.

What he saw when I did made him whistle like a mechanic eyeing the kind of busted engine that could pay a weeks rent. Still, Doyle did his due diligence before telling me the extent of the damage. He traced my spine with his firm Olympians hands then squeezed the back of my neck and dug into the soft flesh above my hips, those little pools of fat where apparently all my nerves were congregating.

When I sat up and pulled on my shirt, he looked me straight in the eyes and let me have it. A person your age should not be in the shape youre in, he said flatly. You need to do something and soon.

The shape I was in, as Doyle saw it, was this: I was infirm, unfit, inflexible, stressed-out and held up by a trail of vertebrae that was more curly straw than human spine. And what I soon needed to do, as Doyle saw it, was stop working twelve-hour days, take time out for myself and start exercising (though he added that launching into a full-blown boot camp, as I had done the week before visiting, had probably been too ambitious).

I dont want to be dramatic, he said, before a particularly dramatic pause. But if you dont change your ways, youre not going to live very long.

Then he softened the prognosis, a little.

Youre not going to die tomorrow, Joel, but youre not going to live to be an old man. The way youre going now, youre not going to live as long as most of your friends.

And Id come in thinking I just had a slipped disc.

When I say I first realised at twenty-eight that I was going to die, I dont mean it took me almost three decades to understand that death was a thing and that it was inevitable, even theoretically for me. I knew that people and animals and flowers died Id seen it happen to all three and I knew that I came from dust and to dust I would some day return. Im Catholic-ish: old men have been telling me that sort of thing since before I could walk.

But for a long time, the idea of death occupied the same corner of my mind as winning the lottery or having group sex: I knew these things happened to some people, especially in films, but I could never quite fathom them happening to me. Dr Doyle changed all that. Not only did he confirm that I was going to die and I was probably going to go out in the unspectacular fashion of a heart attack but he gave me a timeframe: sooner than Id bargained for.

Barring disease, accident or severe ill-health, people rarely talk to you about your own death when youre in your twenties. You dont sit down to write a will in your twenties. You dont sign up for life insurance. You dont typically find yourself at funerals for your friends. If you do, its a shock, an aberration someone your age dies and its still very much tragic; no one is going to call twenty-eight a good innings.

My first reaction to someones raising the spectre of my death was to try not to die, or to at least work on that time-frame. Which meant addressing the thing that was going to do me in.

According to Dr Doyle, my bottom and its fondness for cushioning was a big part of the problem. Did you know that sitting is a disease? he asked once, while pasting electrodes to my back. Far from simply being a position that humans like to be in, he went on to explain that sitting had recently been classified as a condition from which a significant portion of the population, mostly office workers, is suffering. It isnt just the damage that sitting for long bouts does to your back particularly if you, like me, find the ergonomically recommended ways of filling a chair far too hilarious-looking to follow, like being that irritatingly over-eager kid in kindy determined to catch the teachers eye by sitting up the straightest at storytime (I was definitely always that kid). But extended periods of sitting can slow organ function along with muscle contractions that are vital to clearing glucose and fats from the blood stream. Sitting, he told me, is like shutting yourself down.

He wasnt wrong: the American Medical Association last year officially recognised the health hazards of sitting. I know because I looked it up the night Doyle set me straight, along with looking up ways to counteract the health hazards all my sitting was causing. Not surprisingly, standing was involved.

And so, several times throughout the day, I began winding a lever on my adjustable desk at the office to raise it to my waist, so I could do my work standing up for a spell. I also, as recommended by Doyle, walked to the stationery closet every so often to fetch Post-it pads I had no use for, just to break up the day and stretch my legs. I began walking to work, too, taking stairs instead of escalators where possible and planking in the living room to strengthen something he called my core.

This didnt last too long, of course. I soon slipped into old habits like sitting at desks and on buses and on couches. Chairs of all forms were just so convenient, I decided, that I couldnt ignore them. Or at least I chose not to ignore them for very long; my newfound mortality jolt was strong, but it was struggling in the battle against my long ingrained and very male tendency to shrug off anything medically concerning. For most of my immortal twenties, there was no ache a Nurofen could not cure and no anything else a Codral (original formula) couldnt fix. And because back pain tends to be a boom-and-bust type deal it comes in big body-crunching waves when the pain again retreated to a dull roar, I took my foot off the panic pedal and slouched once more.

But while my body went back to slouching and not-stair-walking after Doyles not-so-pep talk, my brain could not quite let go of the compact little Olympians warning. Even as I stopped doing what I needed to do to prolong my life, thoughts of my death took hold.