Afterword

Dena J. Polacheck Epstein

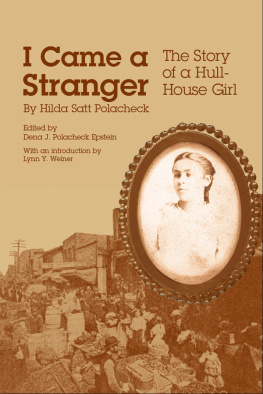

A bout 1953 my mother, Hilda Satt Polacheck, wrote her autobiography at my home in New Jersey, relying principally on her memory, for she had no diary. She felt it was important to tell how an immigrant Jewish girl from Poland became an American at Hull-House, Chicago's first and most important settlement house. It was a way to repay, in part, her debt to Jane Addams and the other people at Hull-House who had done so much to change her life for the better. Although she probably did not know it, her story is the only known description of Hull-House written by a woman from the neighborhood.

When the manuscript was finished she wrote to Dr. Alice Hamilton, asking her to write an introduction. Dr. Hamilton replied that she would be happy to write one as soon as publication arrangements were made. When Dr. Hamilton died in 1970, at the age of 101, three years after Hilda's death, a publisher had not yet been found.

The editors to whom Hilda had introductions rejected the manuscript. Who wants to read about an obscure woman like you? she was told. Write a biography of Jane Addams. We might be interested in that. She made several attempts to rewrite the manuscript to meet their requirements, but eventually she gave up, deeply disappointed. She knew she had lived through important events; she knew she had a story that needed to be told. Three months after her death on 16 May 1967, Hilda's family and friends held a memorial gathering in the second-floor dining room at Hull-House. Excerpts from her autobiography were read by her granddaughters and some friends. I promised myself then that I would try to complete the task she had left unfinished.

Years passed before I could turn to Hilda's manuscript. What I found were loose sheets of various kinds of paper. The first step was to sort this jumbled mass into coherent manuscripts. Eventually seven different versions emerged, all of them incomplete. Some had whole chapters missing, possibly the result of attempts to publish them separately, although none of them were published as far as I know. Others were mere fragments, as though she had tried to begin again but had given up after a few pages. A supposedly complete version had been given to Hull-House by one of her grandsons, but it too proved to be incomplete. All the versions shared an ambiguous chronology and a casual attitude toward dates.

When the sorting was finished I tried to assemble a complete version from seven incomplete ones. Incidents included in some accounts were omitted in others, and statements of her age were inconsistent. Fortunately, two more versions turned up, one in my sister's house and one in the hands of a nephew, carbon copies that had not been changed. With their help I was able to assemble a complete manuscript, although not necessarily the original version.

For the sake of historical corroboration, I tried to find outside documentation for as many statements in the manuscript as I possibly could. In casting about for likely sources, I remembered a box of letters Hilda had given me many years before, letters that she had exchanged with my father during their engagement. For the first time the box was opened and the letters were put into chronological order. What emerged were virtually two parallel diaries, one written in Chicago and the other in Milwaukee from the spring of 1911 until their marriage in April 1912. They wrote almost every day, letters that were wide-ranging in the topics they discussedthe fight for woman suffrage, settlement work, plays, music, family problems, socialism, sex, morals, and business.

According to my birth certificate, my mother was two years older than my father, but the letters hinted that she was either four or six years older than he was. She wrote on 31 October 1911 that she had been cautioned, don't marry a man six years younger than yourself. young men, even boys, have worshipped older women until they reached a certain age, then they (the men) realized that they were poorly mated. On 2 November she wrote: I have such good news to tell you. I looked up the history of the Brownings today and found that E.B.B. was 41 years of age when she married R.B. while he was 35. Shall we wait until I am 41 and you 37?

Ascertaining her true age was important for evaluating her statements of age at various stages of her life. Different versions of her manuscript gave her age on coming to America as five, six, or seven. I estimate she must have been almost tenan age that would explain how she remembered so much of Poland and why she was permitted to do things a five-year-old would probably not do. Establishing her true age also helped in estimating the date when she left school to go to Hilda was born in 1882, not 1886 as she had later claimed.

It seemed likely that this was not the first time she had tinkered with her age. Although she gave conflicting stories of her age when she left school, circumstantial evidence leads to the conclusion that she probably changed her age to get working papers when she was thirteen, before she was legally qualified for them. Altering one's age had been common among the poor of eastern Europe as a means of survival under autocracy, and the practice was easily transferred to America when a poor family needed the wages of its children.

The death of Hilda's father only a year after the family arrived in this country was a disaster. Hilda, at age eleven, was too young to grasp fully her mother's plight, but the impact of the tragedy was evident to her. Her mother had been torn from a comfortable life within a large extended family that viewed life as she did and brought to a strange country. Here she found dirty streets, foul smells, and strange faces. If her husband had died in Poland, she could have depended on informal social patterns that would continue to include her and her children in the Jewish community, while her male relatives saw to her well-being.

My grandmother was a conservative woman who accepted wholly her traditional role of Jewish wife and mother. With her husband's death, her links to the Jewish community died. She was left not only poor and widowed but isolated. When circumstances forced her to become the breadwinner for the family, she retreated into herself. Her piety became profound. In 1912, when Hilda's fianc proposed sending her a book, Hilda discouraged him, writing, She only reads her Bible. The fact that she never learned to speak English symbolized her dislocation in America.

In contrast, Hilda was adventurous, forward-looking, eager to try new things; their relations must have been stormy at times. But as long as Hilda lived at home, she respected her mother's wishes and did not write on the Sabbath. Her letters include such lines as, Just a note because it is Friday and Mother does not want anyone to write on the Sabbath.

The family remained isolated from the activities of the Jewish community in which they lived. Hilda never referred to attending religious services or being a member of a congregation. Perhaps it was not expected that a widow would participate in largely male activities. Hilda did describe her mother's efforts to enroll her sons in a heder (Hebrew school), but they refused to stay, going in the front door and out the back. Coming to America as small boys, they would have remembered very little of their life in Poland and most likely wanted to grow up as Americans. Apparently they were more interested in athletics than in Hebrew school. The youngest, Max, became a star basketball player on the Hull-House team.

It is curious how little space Hilda devoted to her three brothers. Only the oldest, Willie, is even mentioned by name. Apart from their participation in Hull-House athletics, the boys seem to have displayed little interest in Hull-House and its more intellectual activities. Their interests diverged from Hilda's, and they did not share her enthusiasm for education and social causes.