PIONEERS IN MEDICINE

FROM THE CLASSICAL WORLD TO TODAY

INVENTORS AND INNOVATORS

PIONEERS IN MEDICINE

FROM THE CLASSICAL WORLD TO TODAY

EDITED BY SHERMAN HOLLAR

Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the

Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group, Encyclopdia Britannica

Adam Augustyn: Assistant Manager, Encyclopdia Britannica

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Michael Anderson: Senior Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Andrea R. Field: Senior Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Sherman Hollar: Associate Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Rosen Educational Services

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Karen Huang: Photo Researcher

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Hope Lourie Killcoyne

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Pioneers in medicine: from the classical world to today/edited by Sherman Hollar.

p. cm.(Inventors and innovators)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-741-8 (eBook)

1. MedicineHistoryJuvenile literature. 2. Medical innovationsHistoryJuvenile literature. I.

Hollar, Sherman.

R133.5.P46 2013

610dc23

2011040173

Cover, p. 3 www.istockphoto.com/Chepko Danil Vitalevich; interior background image (pipette and

petri dish) www.istockphoto.com/malerapaso

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

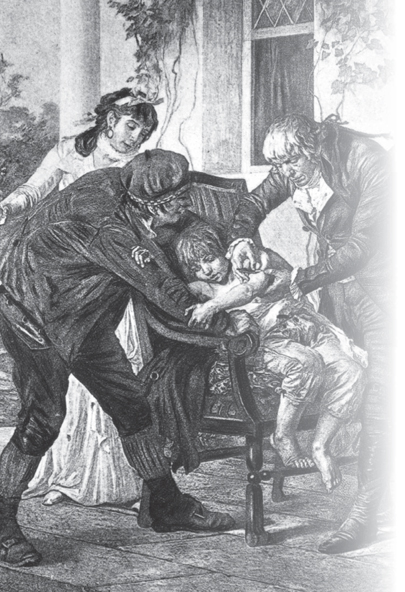

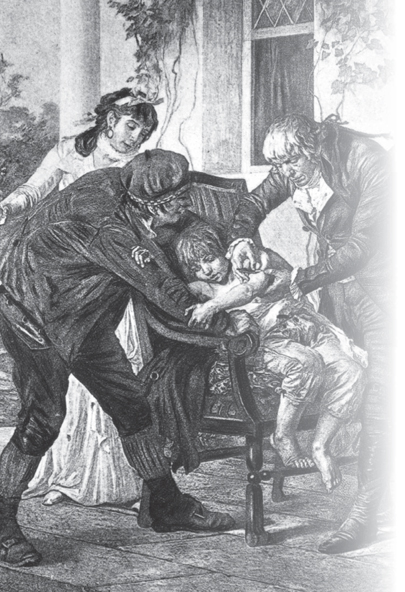

Edward Jenner makes historyand in this 18th-century depiction, draws a small gathering of onlookersas he inoculates an eight-year-old boy with cowpox virus, the first such procedure of its kind. Three Lions/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

O ne sure way to both help humanity and gain a place in history is to tackle a seemingly unstoppable disease. For Walter Reed it was yellow fever. For Jonas Salk, polio. But in order to create a cure, one must break with the past. And doing things that have not been done beforeespecially when lives are on the linecan lead to opposition. Take the case of Edward Jenner. As a young apprentice to a doctor in 18th-century England, Jenner had heard a farm girl tell the doctor that she could not contract smallpox because she had already had cowpox. Years later, after much experimenting with that notion of resistance based on prior exposure, Jenner, then a doctor himself, went so far as to inject a healthy eight-year-old boy with cowpox. Two months later he exposed him to smallpox. Jenners experiment was met with scorn and incredulity. But it worked. And so in time, enough other doctors started using the same preventative method, one which Jenner had given a now-familiar name: vaccination.

Sometimes a medical advance was as basic as insisting upon cleanlinessnamely, noticing that the simple act of washing hands could stop the spread of infection. Such was the now elementary but then revolutionary contribution of 19th-century Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis.

That notion of maintaining sanitary conditions was one that 19th-century English nurse Florence Nightingale championed as well. In her case, doing so in the military hospitals of Scutari, Turkeyused as a troop base during war between England and Russiawas extremely challenging. There, soldiers were dying more as a result of infection than of battlefield wounds. By her own rigorous insistence upon sanitary regulations, as well as the introduction of special diets, Nightingale brought down the death rate from 45 to 2 percent. And for the renowned 19th-century German physician Rudolf Virchow, public cleanliness and proper hygiene became something of a crusade, Virchow going so far as to design the sewage system of Germanys capital, Berlin.

If at first you dont succeed, inoculate, inoculate again. Such might be the motto for 19th-century French chemist Louis Pasteur. Best known for his discovery of the pasteurization process, in 1882 Pasteur turned his attention to rabies, beginning careful and repeated trials in which he attempted to halt the development of rabies in infected animals. He eventually succeeded in curing an infected dog after inoculating the animal 14 times.

And it just so happened that three years later, the number 14 would again resurface in regard to rabies for Pasteur, as it happened to be the number of times that a nine-year-old boy had been bitten by a rabid dog. Though reluctant to try his remedy on a human, at the fervent request of the boys mother, Pasteur did so. The wounds healed and no rabies appeared, making the boy the first human saved by Pasteurs cure.

As readers travel through time in this book meeting healers through the ages, they will also discover tidbits about the lives of those profiled, such as which doctor was challenged to a duel by German chancellor-to-be Otto von Bismarck, which famous doctor married the great-granddaughter of Paul Revere, which nurse was arrested and jailed for her efforts to educate women about birth control, and which psychiatrist came up with the now-ubiquitous personality designations of introvert and extrovert. (Nope, not Freud.)

From Asclepius, the mythic Greek god of medicine, to Hippocrates, the father of medicine, and on to inspiring medical mavericks such as Alexander Fleming, who brought the world penicillin, and Margaret Chan, whose leadership helped avert the widespread outbreak of deadly diseases, Inventors and Innovators: Pioneers in Medicine: From the Classical World to Today presents a clear, concise, and captivating compendium of those who have improved the health and welfare of millions the world over.

CHAPTER 1

ASCLEPIUS

T he Greek god of medicine, Asclepiusin Latin, Aesculapiuswas the son of Apollo (god of healing, truth, and prophecy) and the mortal princess Coronis. Asclepius was brought up by the centaur Chiron, who taught him the art of healing. At length Zeus (the king of the gods), afraid that Asclepius might render all men immortal, slew him with a thunderbolt. Apollo slew the Cyclopes (monstrous one-eyed giants) who had made the thunderbolt and was then forced by Zeus to serve Admetus, son of the king of Pherae in Thessaly. The words panacea, a nonexistent remedy for illness, and hygiene, conditions and practices conducive to health, come from Asclepiuss two daughters, Panacea and Hygieia.

Next page