Copyright 2012 by Purdue University. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jack, Zachary Michael, 1973-

The Midwest farmers daughter : in search of an American icon / Zachary Michael Jack.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-55753-619-8 (paper : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-61249-219-3 (ePDF) -- ISBN 978-1-61249-218-6 (ePUB) 1. Women farmers--Middle West. 2. Farm life--Middle West. 3. Middle West--Social life and customs. 4. Women farmers--Middle West--Public opinion 5. Farm life--Middle West--Public opinion 6. Middle West--Public opinion 7. Women in mass media. 8. Farm life in mass media. 9. Popular culture--United States. 10. Public opinion--United States. I. Title.

S521.5.M53J33 2012

630.82--dc23

2012004918

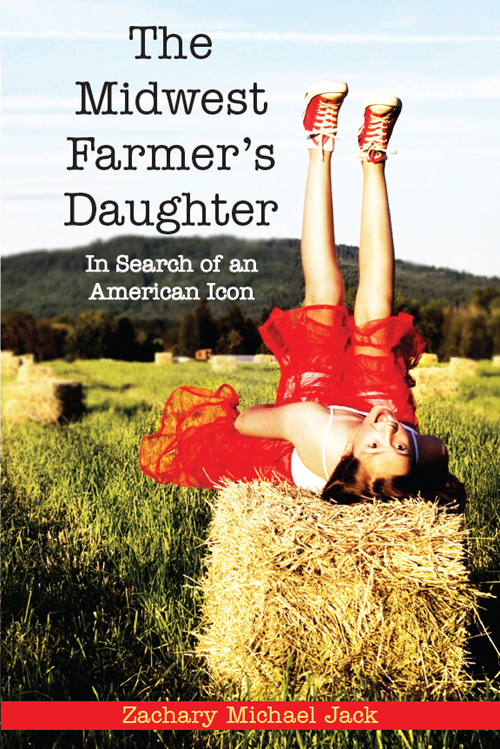

Cover image: The Prairie Was Her Playground

copyright 2008 Lara Blair Images / www.modernprairiegirl.com

PREFACE

PIONEERING WOMEN

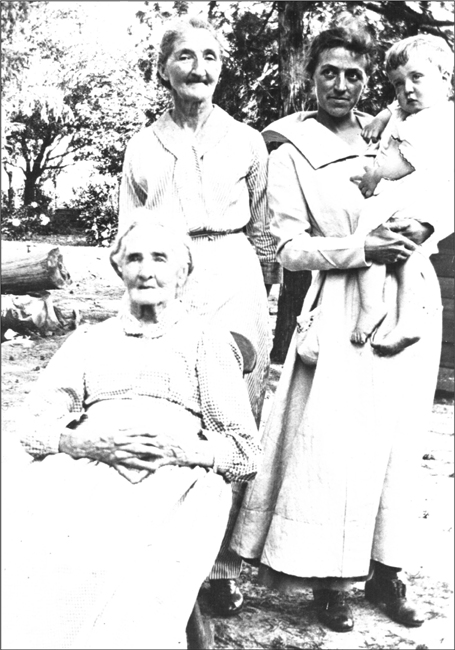

T HE STORY OF a Pioneer Cedar County Farm headlines the account of my ancestor Levi Pickerts settling of our midwestern family farm. The next year, 1855, he again came out to Iowa, the recounting goes, bringing not only his wife and son, but his father and mother also.

So begins the history of my people, and the plot advanced as they planted seeds real and metaphorical in the good midwestern dirt. Yet while the presumed protagonist of the pioneering drama, Levi, earns multiple mentions, his helpmate in life remains nameless but for the unremarkable moniker wife. As the pioneering history unfolds with its breathless stories of the coldest winter in Iowas history when, for forty consecutive days it did not thaw, climaxing in tales of hangings and horses thieves on a frontier where trees in the vicinity [had] been decorated with the bodies of desperadoes, the very name of Levis life partner is lost to the wind, a sound and fury, signifying nothing.

By my late twenties I could recite the names of my male farming forebears on the Pickert side as far back as the early 1800s. But had I been asked to name a wife or daughter predating my great-grandmother, I would surely have come up empty, not because I was a poor student of genealogy, but because the names were seldom found in print. It wasnt until my thirties, in fact, that a bundle of letters Id chanced upon revealed to me the hearts of the familys farm daughters, making them, quite literally, something to have and to hold.

In one letter datelined 1867, Syracuse, New York, Eliza Smith writes her long-lost sister, my great-great-great-grandmother Sally Pickert, wife of Levi, to observe, This world is full of sorrow and disappointment. We was very glad to hear from you once more and know that you are alive, but I think you will not live long if you keep on working so hard as you do. What profit will it be to you to have it said that you were rich after you are dead? I have seen the folly of working so hard for greater riches and see them take wings and fly away. Sally, you do not know how much I want to see you and talk with you. I have so much to say that I cant write...

The earliest missive Sally saved, dated 1855, would have arrived while she, Levi, and her in-laws shared a one-room schoolhouse with four other families, according to a 1962 article in the Cedar Rapids Gazette entitled Three Generations of Pickerts Have Lived in Mechanicsville House. The Pickerts arrived in Davenport, Iowa, in 1854 by train from Waterton, New York, the Gazettes Amber Jackson reported, and began walking west until they came upon the 200 acres of black earth that would become our Iowa Heritage Farm, purchasing the ground from David Platner for the bargain price of $10 an acre. Jacksons recounting makes no mention of the female partners in the enterprise beyond the wife-obscuring umbrella The Levi Pickerts, nor does it mention the baby Sally lost in that first unforgiving year in the Heartland.

Your Uncle Ben told me he would give $100 if you would come back, another New York relative named William Wallis conveyed in his own note to his far-flung Iowa relatives. But there would be no such turning back for pioneering families, not for love or money, no diminution of the arcadian dream of mother and father, daughter and son, cultivating the countryside for generations. To the yeoman the dream seemed unerring, the yield perennial. The farmers son may have made the harvest possible, but the daughter made it worthwhile.

A ND STILL TODAY the same reverie comes each spring, the scenes are the same. Everything, in fact, save for the little girl, my great-grandfather Walter Thomas Jack wrote of his own farmers daughter, Helen, in his book The Furrow and Us. She has grown up now and has gone, but imagination keeps her on the set, and her role will always be that of the leading lady. Still, even as Grandpa Walt penned homage to his own long-gone girl of 1943, powerful cultural and economic changes had already swept many a farms leading lady from her bucolic perch. Lovely Helen Jack proved a case in point: she had grown up, married, and moved off the farm into secretarial work at the John Deere Company in Moline, Illinois, leaving her father behind to pine. Great-grandpas reverie of a girl bedecked in Easter finery was a song, he insisted, that clings to us throughout our whole lives. Neither time nor eternity can take away the particularity, and as time passes, the charm of it remains radiant, immortal, he opined, though he might have classed the same phenomena as a bona fide haunt.

It had been some Rip Van Winkle sleep, surely, in which she had slipped away, his girl of spring. In the pages of Walts wartime glossies, after all, agricultural daughters like Helen Jack werent pictured at desks taking rote dictation for ungrateful bosses; instead they were shown astraddle tractors, tilling the good earth while wearing straw hats and white work shirts rolled at the sleeve, frisky farm collies following in their wake. The advertisements in great-grandpas

WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA

WEST LAFAYETTE, INDIANA