T HE HAUNTING MELODY of a Beethoven piano sonata played softly in the background as I gazed into the slit of darkness evolving before my eyes. I handed another small stone to Achmed, who in turn handed it up the ancient white steps to be added to the growing pile of rubble. Beethoven would no doubt have been incredulous that his Appassionata served as the sound track for such a remarkable scene: the opening of an ancient Egyptian tomb, in the famed Valley of the Kings. It was actually a reopening of this particular tomb, myself being perhaps the fourth person to have done so, I reckoned, over a period of over three millennia.

As I carefully removed the stones, I marveled at the situation in which I found myself. Here I was, in the most famous archaeological site in the world, following in the footsteps of earlier explorers who were likewise entranced by this ancient place. The vertical limestone walls of the valley soared nearby, their golden hues becoming increasingly lighter due to the same intense summer sun that baked us as we worked in the vanishing late-morning shade. What tales these cliffs could tell, having borne witness for centuries to episodes of passionate human drama, the sweat of ancient workmen, the tears of the bereaved, and, now, the drama of modern archaeological discovery.

A view looking down the Valley of the Kings.

Denis Whitfill/Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) Valley of the Kings Project

Approximately thirty-four hundred years ago, one of the most powerful men on the planet, the mighty pharaoh, Lord of Upper and Lower Egypt, Akheperkare Thutmose, commanded that a secret tomb be constructed for his burial in the arid Theban mountains. Unfortunately, the pyramids of his predecessors now stood only as towering beacons calling out to the treasure-minded and had proved to be utter failures when it came to protecting the remains of those considered to be god-kings. Thutmose had instigated a new strategy in the hope of better ensuring his eternal security by building a hidden tomb carved deep into the bedrock in a remote desert valley unseen by the masses with an immense peak hovering nearby, whose natural shape provided a symbolic pyramid over the royal grave. Thutmoses tomb would initiate the Valley of the Kings as the burial place for three dynasties of rulers during the historical period referred to as the New Kingdom, which would span approximately five hundred years, from about 1500 to 1000 B.C. It was this royal cemetery that was the stage for our unfolding tomb opening. Just a few minutes walk from where we were lies the tomb of the famous warrior pharaoh Rameses II and, not far beyond, that of Tutankhamun, the obscure, short-lived king whose virtually intact tomb brought him lasting immortality in the modern world. And just a few dozen yards from our dig is the original tomb of Thutmose I, a deep, dangerous subterranean sepulcher, expanded and later utilized by his daughter, the remarkable female pharaoh Hatshepsut.

The early tombs in the valley were well hidden, often in fissures in the cliffs or in other places easily concealed. Those of the later pharaohs typically boasted large, obvious entrances carved into the valleys limestone. The magnificently painted corridors that followed led to an imposing stone sarcophagus holding the mummy of the king. Like the pyramids, the Valley of the Kings, too, in the long run, would prove to be a failure in guarding against the greedy. Many of its tombs would be robbed even while the cemetery was still in use.

As early as the third century B.C. , several of the tombs were tourist attractions to Greek and Roman sightseers who came to marvel at the remains of the past, much as we do today. Many of them even left evidence of their visit in the form of graffiti, which can still be seen and read today scrawled on the walls of several tombs.

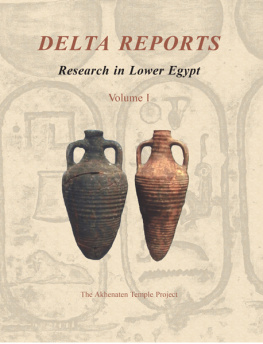

A view of the general vicinity of KV 60. The man in the photo stands above the location of the tomb. The entranceway to KV 19 was cut directly over KV 60, and its door is situated to the right. Just above, in the shadow of the cliffs, is KV 20, the royal tomb of the pharaoh Hatshepsut.

PLU Valley of the Kings Project

Some of the valleys tombs would later serve as austere housing for reclusive Christian hermits, and some would suffer the devastations of flash floods and other natural and human indignities. Ultimately, few of the pharaohs survived in their intended final resting places. Most of their ravaged mummies were gathered up by ancient priests, rewrapped, and stowed in secret caches where they have been rediscovered during the last century or so.

Like most archaeology in Egypt, the Valley of the Kings has a rich history of exploration. Although the location of the valley was long known to European travelers, it wasnt until the arrival of Giovanni Belzoni in 1816 that excavations actually began in our modern era (more on him in another chapter). Then, in 1827, John Gardner Wilkinson wandered about the valley with a container of paint, boldly numbering each known tomb as he went along and establishing a numbering system that provided a ready frame of reference for the scholars and archaeologists who followed. Although Wilkinson got only as far as the number 21, the system would eventually extend to 63, the number that has been assigned to the last new tomb discovered as of this writing, a bizarre cache of mummyless coffins uncovered in 2006.

While the Valley of the Kings is certainly one of the most celebrated sites of antiquity on earth, most people (archaeologists included) are unaware that among the thirty or so beautifully decorated royal tombs lie an approximately equal number of typically small and uninscribed tombs, whose very presence in the valley actually bespeaks some sort of great importance. Some consist merely of a shaft leading to a single rectangular burial room, while others contain a corridor or two and steps that eventually lead to a final chamber. These tombs, whose blank walls routinely render their deceased occupants anonymous, were until recently considered of little interest to Egyptologists. Readily identifiable art and writing on the walls of the bigger royal tombs are certainly alluring and have long attracted the majority of scholarly attention.