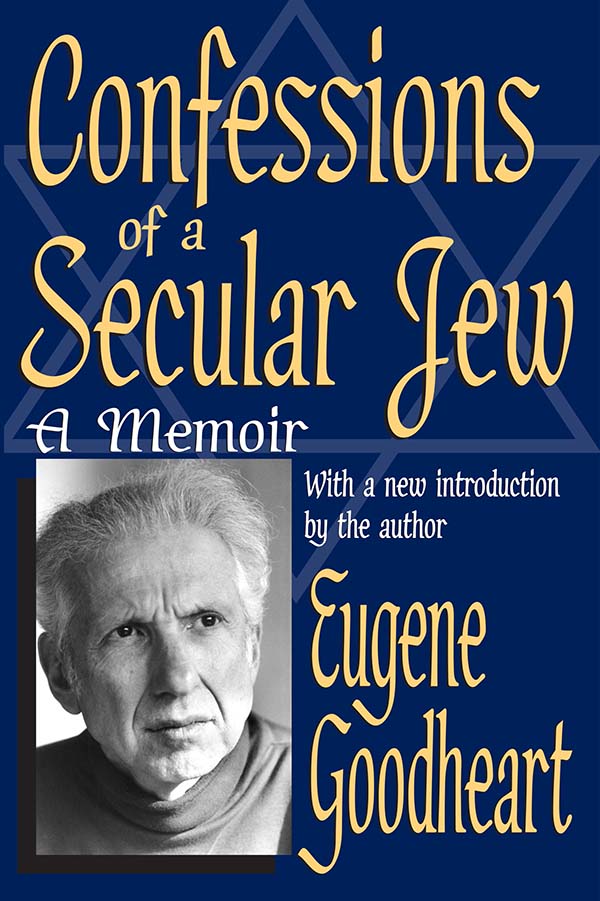

Originally published by The Overlook Press in 2001 Published 2005 by Transaction Publishers Published 2017 by Routledge

Published 2005 by Transaction Publishers

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition Copyright 2005 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2004055367

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goodheart, Eugene.

Confessions of a secular Jew: a memoir/Eugene Goodheart, with a new introduction by the author.[2nd ed.] p. cm.

ISBN 0-7658-0599-5 (alk. paper)

1. Goodheart, Eugene. 2. JewsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Jews Cultural assimilationUnited States. I. Title.

E184.37.G66A3 2004

973'.04924'0092dc22 2004055367

ISBN 13: 978-0-7658-0599-7 (pbk)

Introduction to the Transaction Edition

To begin with, the matter of genre. What is the difference between autobiography and memoir? An autobiography is supposed to cover a whole life, a memoir only a portion of it. In this respect, my book is closer to autobiography than to memoir. But there is another crucial distinction between the genres. Autobiography is personal history, which requires you to report that past with the accuracy of an historian. You need to get the facts right to the best of your ability. The medium of memoir is memory, which is not always reliable as to fact. Memory refracts the past in a way that history does not or is not supposed to. But if the memoirist is not always faithful to the fact, he must not betray memory. The way he remembers reveals who he is. In this respect, I have written a memoir rather than autobiography. What does it mean to be faithful to ones memory? Nietzsche once said that in the contest between memory and pride, memory always yields. The terms, however, cannot be so easily separated. Memory can be self-serving as I discovered in the writing, and there may be pride and courage in ones fidelity to a memory that admits humiliations and bad behavior. Nevertheless, the distinction captures the struggle in the writer between expressing and holding back what he remembers of his past.

Here is a confession that I did not make in the memoir: the title was an afterthought. I did not set out to write about being a secular Jewas if it were a phenomenon as definable as being an Orthodox or Conservative or even Reform Jew. We know what a secular Jew is not, a religious Jew. We might rest perhaps with the positive idea that he is a worldly Jew, but is that sufficient to define him? ReligiousJews may also be worldly. Hasidim, for instance, are famous as diamond merchants. If worldliness were all that secular Jewishness comes to, it would seem not to come to very much. Notice I refrain from speaking of secular Judaism, because of the religious connotations and associations of Judaism. Abstract definition is a fruitless effort. The title emerged from reflection after I had completed the writing.

The author reading Itzhik Feffers poem I am ajew. (Feffer seated third from the left).

The germ of the memoir is a personal essay I published with the title I am a Jew. Enclosed in quotation marks because it is a translation of the title of a Yiddish poem by a once famous Soviet Jewish poet Itzhik Feffer. The poem is a celebration of Jewish struggles for liberation from the time of Moses through the Maccabean uprisings against the Syrian Greeks, Bar Kochbahs revolt against the Romans to the Soviet struggle against Naziism. Here is the opening stanza of the poem:

The forty years in ancient times

I suffered in the desert sand

Gave me strength.

I heard Bar Kochbas rebel cry

At every turn through my ordeal

And more than gold did I possess

The stubborn pride of my grandfather

I am a Jew.

As a kid, I attended a Yiddish shuleh where I learned to recite, better to declaim, Yiddish poems in public. (The shuleh was sponsored by the Jewish Peoples Fraternal Order of the International Workers Order [the IWO]. During the McCarthy period in the early 1950s, the IWO had been placed on the attorney generals list of Communist front organizations.) One of the poems I learned was Ich bin a Yid. In the memoir, I describe my experience of reciting the poem in Yiddish to a large audience in Feffers presence on the occasion of his visit to Camp Kinderland, a summer camp of the IWO, in upstate New York, where I was a camper. One of my gifts was the possession of a Yiddish diction that one hears on the Yiddish stage. How I acquired this precocity I cannot say, but I had an extraordinary ear for the words and cadences of Yiddish poetry and was in demand by Yiddish-speaking clubs to recite Yiddish poems. It was a great event of my childhood. The poem celebrates the achievements of the Soviet Union and its leader, Joseph Stalin. Despots love to be celebrated in poetry. But the rewards Feffer received for his flattery did not last. Several years later he was denounced by the Soviet regime as a traitor.

Joshua Rubinstein of Amnesty International has recently published a book, Stalins Secret Pogrom, about the persecution and prosecution of fifteen Soviet Jewish writers on trumped up charges of treason. All were executed, among them Itzhik Feffer. I did not expect to be surprised by the book. I thought it would merely confirm what I had long ago come to believe about the regime. But I was surprised by the grotesque disparity between the innocuousness of the charge against the defendants and the enormity of the punishment. The crime was little more than nationalist sentiment that itself constituted treason. There was no evidence that the expression of pride in ones Jewish identity and sorrow at the price paid for being Jews at the hands of the Nazis was at the expense of loyalty to the Soviet Union. What also surprised me was the effect of the trial (indeed of the Soviet system) on the integrity of the defendants. Each defendant protested his loyalty to the regime at the same time that the regimes attitude to him and her (there was one female defendant) was execrable. Fear undoubtedly was a motive, but there was also an inextinguishable devotion to a cause that had gone awry. One writer, Kvitko, testified that the October revolution had brought him to life. Though the defendants had confessed under torture, a number of them displayed courage at the trial in defending their innocence and exposing the injustice of the proceedings. The format of the trial was diabolical. The judge was the prosecuting attorney, who refused to believe any statement in court that contradicted the confessions. Even more diabolical was the permission given to each defendant to challenge the veracity of another defendant. Despite the prosecutorial strategy of divide and conquer, many of them behaved admirably. The most craven of the defendants was my childhood hero, Itzhik Feffer.