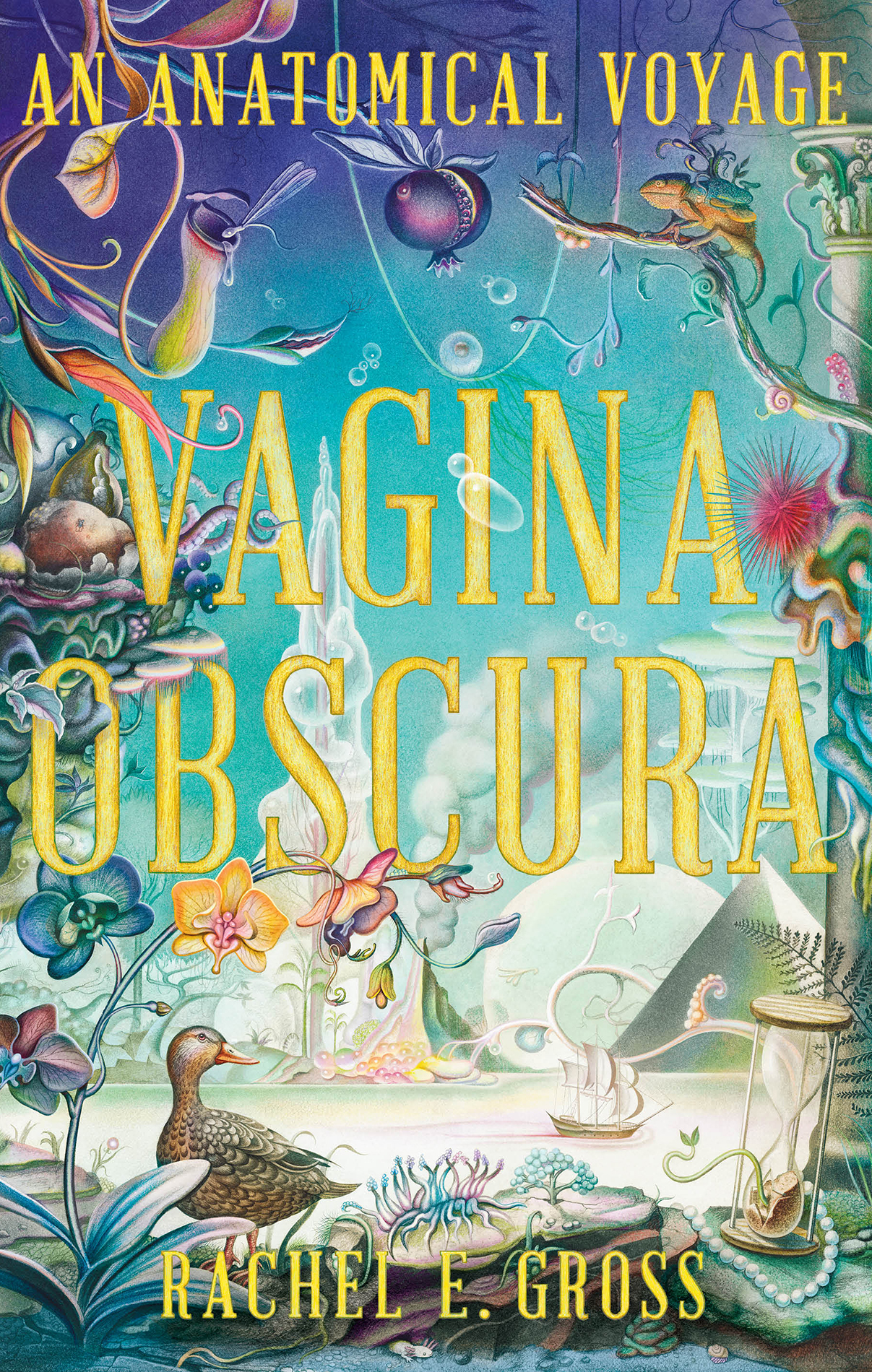

Vagina Obscura

Would it not for this they would have no desire nor delight.

BRITISH MIDWIFE JANE SHARP, 1671

Vagina

Obscura

AN ANATOMICAL VOYAGE

RACHEL E. GROSS

With Illustrations by Armando Veve

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

This book was written for any womanany personwho has found themself mystified by their own body. Anyone who has felt the nagging suspicion that what they have read about their anatomy wasnt written for them, or by someone like them. You were right. This book was written for you. It was written for anyone who has felt unable to talk about their body in language that others could understand. Anyone who wants to better understand the legacy they were born with, by virtue of their reproductive organs and the chromosomes dancing within their every cell.

I hope this book welcomes you in as the remarkable women and explorers in this book welcomed me.

There comes a time in every womans life when her body bumps up against the limits of human knowledge. In that moment, she sees herself as medicine has seen her: a mystery. An enigma. A black box that, for some reason, no one has managed to get inside. Those that I talked to for this book were all made to feel that they alone had a complicated, unruly body. They began to suspect, or were outright told, that somehow it was their fault. That they should be ashamedshould lie down and think about what theyd done.

My own moment came in July 2018. I was twenty-nine years old, and I had an itch I couldnt scratch. For the past month my vulva had felt on the verge of bursting into flames. At first my gynecologist, a tiny, no-nonsense woman named Dr. Lori Picco, thought I had a particularly exuberant yeast infection. But one antifungal treatment and two rounds of antibiotics later, she had bad news: my tormentor was a bacterial infection Id never heard of. For half of women who get it, it pops back up again and again, without warning, like a Whac-A-Mole.

There was one last treatment I could try. Its basically rat poison, said Dr. Picco. Youre going to see that on the Internet, so I might as well tell you now. It was called boric acid, and thanks to its fungi- and bacteria-killing powers, its been used since the 1800s in antibacterial ointments, douching washes, and roach and ant killers. The idea was to nuke the ecosystem inside my vagina, wiping out the bad bacteria along with the good, so I could start afresh.

That didnt sound great. But neither did having a lifelong infection.

More than most, I was primed to take my doctors suggestion. I was the daughter of scientists, a medical doctor (my mother); a theoretical physicist (my father); and a molecular geneticist (my stepmother). I had a masters degree in science journalism and worked as the digital science editor at Smithsonian magazine, where I fancied myself fluent, or at least conversational, in things like cells, biology, and bodies. To a large extent, I trusted medicine. I certainly trusted Dr. Picco, who had always approached my vagina with a curt, businesslike efficiency.

I took my poison like a good patient, every night, on my back. For ten days. But one night, I made a mistake. Exhausted from weeks of surreptitious itching, thinking about itching, and trying not to itch, I passed out early. When I woke up again, it was three a.m. and I had the tingling feeling that something was amiss. I stumbled to the bathroom, half-awake, and unscrewed my orange pill container. Then, without thinking, I swallowed my vagina poison.

I sat down on the toilet, hard.

I took out my phone and typed frantically into the Google search bar. The top result was a study entitled: Fatal ingestion of boric acid in an adult. Boric acid is a dangerous poison, it began. Poisoning from this chemical can be acute or chronic.

I ran back to the bedroom and shook my boyfriend awake. But the words wouldnt come. Until that moment, I hadnt told him about the medication I was taking. Logically, I knew that whatever was happening to me down there had nothing to do with my self-worth. But in the back of my head, I still felt dirty. Contaminated. Radioactive. Like there was a force field of shame around my nether regions. Even for me, even in 2018, you just didnt talk about your burning bush.

I think I swallowed something I shouldnt have, I said, my voice a childs whisper. He took one look at my phone and started putting on his shoes. It was time to go to the emergency room.

On the hospital bed, under the fluorescent lights, I remember feeling profoundly alienated from my body. I pictured myself getting my stomach pumped, convulsed by shockwaves, taken over by a force greater than myself.

Beneath that disconnect was something else. Betrayal. Outrage. This wasnt supposed to happen. I thought of myself as an educated, rational, science-minded woman, equipped with the tools to control my own life. Why didnt I know the inner workings of my own body? Why didnt my gynecologist, or any of the other doctors Id encounteredmedical experts who had spent their lives studying and caring for bodies like mine? Why, for Gods sake, had my gynecologist recommended I shove rat poison up my vagina?

It hit me: I knew almost nothing about how my vagina worked.

That was the moment this book was born.

I set out to write a book on the science of vaginas. It would be fun and jaunty and full of wonder, a Ms. Frizzleesque journey into the intimate depths of the human body. But I soon realized I had a problem: there is a vast knowledge gap when it comes to what we know about the female body. Most of our scientific understanding of this realm is built off of the study of male bodies. It was only in 1993, following the womens health movement, that a federal mandate required researchers to include women and minorities in clinical research. As Dr. Janine Austin Clayton, associate director for womens health research at the National Institutes of Health, put it in 2014: We literally know less about every aspect of female biology compared to male biology.

Until recently, medical research on women in this country was centered mainly on fertility. As I was told by one endometriosis expert: Nobody in Congress really cares about the uterus when it doesnt have a baby in it. Only in 2014 did the NIH start a gynecological branch to look at the health of vulvas, vaginas, ovaries, and uteruses in their own right. That was virtually the first time a federal research branch acknowledged that these organs are integral to womens health, whether or not they intend to get pregnant. (Even that research, however, is housed within the National Institute of Child Health and Development. What part of NIH is interested in lady parts? Its not intuitive, says Dr. Diana Bianci, the institutes director. But in fact it is largely us.)

As a result, there are parts of your own body less known than the bottom of the ocean, or the surface of Mars. Most researchers I talked to blamed this dearth of knowledge on the black-box problem: the female body is considered more complex, more obscure, with much of its plumbing tucked up inside. To get inside it, weve needed high-tech imaging tools, tools that have only come around in recent decades. When I heard these answers, I couldnt help thinking of what science has done in the twenty-first century: put a rover on Mars, made a three-parent baby, built an artificial sheep uterus. And we couldnt figure out the composition of vaginal mucus?

Next page