Roy Kinnard, Tony Crnkovich and R.J. Vitone

To Jean Rogers (1916-1991) in heartfelt remembrance and appreciation

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the following individuals for their contributions to this book: Buster Crabbe (deceased), for consenting to an extensive telephone interview in 1983; Jean Rogers (deceased), for also consenting to a lengthy phone interview in 1981, and for inviting me into her home in Sherman Oaks, California, on several occasions; Carroll Borland (deceased), who shared her memories by phone in 1985; film historian George Turner (deceased), who shared my interest in these films and encouraged me to write this book; Don Lee and Russ Butner of the Margaret Herrick Library (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences); Sandy Williamson and Jeff Pirtle of the Universal Studios Archives and Collections, Document Management Division, Universal City, California; Roni Lubliner of NBC-Universal; Ned Comstock of the University of Southern California (Cinema-TV library), Los Angeles; Josie Walters-Johnston, reference librarian (moving image section), Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Tom Sand; and Ita Golzman and Frank Caruso of Hearst Entertainment. In reflecting on these acknowledgments, my only true regret is the number of times I have had to type the word "deceased" in this paragraph. May God bless all of the above who are no longer with us.- R.K.

Table of Contents

vii

Chapter 8: 65

Chapter 11: 76

Chapter 8: 110

Chapter 9: 113

Chapter 5: 144

Chapter 8: 150

Preface

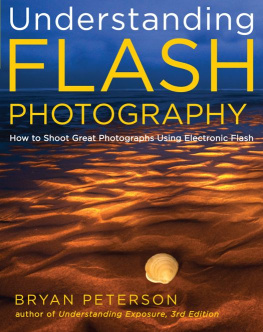

Artist/writer Alex Raymond's newspaper comic strip Flash Gordon debuted on January 7, 1934, and was an immediate hit with a Depression-era public sorely in need of escapist adventure. Conceived by Raymond and the Hearst newspaper chain as competition for the already-established rival strip Buck Rogers, Flash Gordon soon eclipsed Buck in popularity. Tightly plotted and extremely well drawn, Flash Gordon was imbued with swashbuckling romanticism and exotic interplanetary settings that transported world-weary audiences of the time into another, more entertaining world.

The strip quickly became one of those pop-culture sensations that was discussed by readers around thousands of office water-coolers and factory lunch tables the next day. While both Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon were ostensibly science fiction, it was Buck Rogers that emphasized sci-fi gadgetry and jargon, while Flash Gordon, with its towering heroes, beautiful women and unspeakably evil villains, was more fantasy-oriented; Raymond's strip had more in common with the worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs and The Wizard of Oz than the largely austere realm of sci-fi.

In the early 1900s, newspaper circulation, particularly in metropolitan areas, drove every facet of a paper's daily operations. Newspaper baron William Randolph Hearst was a canny publisher who recognized the drawing power of colorful, escapist fare. Comic strips, in both daily and Sunday installments, served to lighten the impact of the often grim daily news, and a popular "talked about" comic strip could increase readership. Hearst's King Features Syndicate sought out, developed, and showcased the comic-strip work of many artists. In a few short years, Sunday comics sections grew from simple fillers to enormous inserts, sometimes using as many as three full-color sections. Every type of feature found its way into these garishly-colored pages; humor, soap opera, historical, crime/detective/mystery, fantasy, adventure and military, all scrambled for the readers' attention. Imitation was inevitable; if a particular western feature generated favorable public reaction, several "new" western strips would appear in short order. Flash Gordon wasn't a direct copy of Buck Rogers, but its creation certainly grew out of that earlier strip's success.

Alex Raymond was a 24-year-old artist who had worked in the newspaper comic strip field as an assistant and "ghost" for other artists. Flash Gordon was his personal creation. A Sunday insert-only, full-page feature, the strip chronicled the interplanetary adventures of Flash Gordon, "Yale graduate and world-renowned polo player." In other words, Flash was a "gentleman"- a WASP in good standing; and who better to battle archvillain Ming the Merciless, whose very appearance suggested the oriental and "foreign," thereby playing into the "yellow peril" slant of Hearst's newspapers? King Features snapped it up, and the strip appeared, full-blown and in full color, in early 1934. Drawing at that time in a tight, blocky style, Raymond packed those early pages with an abundance of plot, and introduced a wide array of characters with dizzying speed, but with narrative clarity. Readers knew in no uncertain terms just what was going on, what the dangers were, and who was on whose side.

Jean Rogers and Buster Crabbe as Dale and Flash.

It's difficult today to even imagine the cultural impact that Flash Gordon had on newspaper readers at that time. There had been science-fiction strips before, but Raymond had virtually reinvented the genre. His work on the strip, particularly as he continually developed his art style to fully illustrate his fantastic vision, represents one of the true milestones of the newspaper comics market. Raymond brought a new artistic depth to the "funny pages." After an early period of experimentation with his characters, Raymond launched Flash Gordon and his extended "family" -Dale Arden and Dr. Hans Zarkov - on a series of outer-space adventures that H. G. Wells (and certainly Edgar Rice Burroughs) would have appreciated.

Flash battled monsters and despotic rulers on every corner of the planet Mongo, all of them controlled by Ming the Merciless, supreme dictatorial ruler of Mongo and selfproclaimed Emperor of the Universe. Ming ruled Mongo with sadistic ruthlessness, consolidating his power by pitting the various tribes of the planet against each other, and, in the process, unwittingly uniting them in their hatred of him. Raymond's stunning artwork vividly transported the reader to Mongo's exotic locales, with his style growing and maturing until, by 1937, his work had attained a high level matched by few others in the field. Given free reign over plot, design, and even page layout, he opened up the Sunday comics page in new, visually exciting ways.

Working at times from live models, he captured unique details with an artist's sensitive perception, as though through a camera lens, and Raymond's creation was a natural for the movies. In 1936, Universal Pictures released the first movie based on the property, a 13-chapter weekly serial starring Olympic swimming champion-turned-actor Buster Crabbe in the heroic title role. Certainly one of the best (and most faithful) live-action comic strip adaptations ever produced by Hollywood, Flash Gordon (with a credit line unabashedly proclaiming it as "Alex Raymond's cartoon strip" beneath the main title) was an immediate hit, spawning two sequels over the next four years.