First printed in paperback format in August 2019.

First published in ebook format September 2019 by Veloce Publishing Limited, Veloce House, Parkway Farm Business Park, Middle Farm Way, Poundbury, Dorchester, Dorset, DT1 3AR, England Fax 01305 250479 e-mail .

Ebook edition ISBN: 978-1-787116-18-4

Paperback edition ISBN: 978-1-787115-72-9

John Starkey and Veloce Publishing 2019. All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review, no part of this publication may be recorded, reproduced or transmitted by any means, including photocopying, without the written permission of Veloce Publishing Ltd. Throughout this book logos, model names and designations, etc, have been used for the purposes of identification, illustration and decoration. Such names are the property of the trademark holder as this is not an official publication.

Readers with ideas for automotive books, or books on other transport or related hobby subjects, are invited to write to the editorial director of Veloce Publishing at the above address.

All ebook design and code produced in-house by Veloce Publishing.

Contents

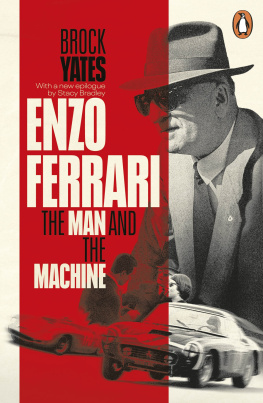

Acknowledgments

The events described in this book took place over fifty years ago. Not many of the main players of this drama are still with us. Jacky Ickx, Brian Redman, David Hobbs are all, thankfully, still here, and all four wrote books that described their part in this drama. But Enzo Ferrari, Henry Ford II, Lee Iacocca, Leo Beebe, Carroll Shelby, Ken Miles, Denny Hulme, John Surtees, Dan Gurney, Mark Donohue, Walt Hansgen, Leo Beebe, John Wyer, Eric Broadley, Roy Lunn and many others involved in this period of motor racing have all passed on.

To write this book, I read many others in which the events of the Ford/Ferrari battle were described, and, having myself written several books about Lola, particularly the Lola T70, the successor to Eric Broadleys Lola Mark VI and the GT40, I had long ago interviewed some of the men from those early years, who had worked on the Mark VI at Lolas little workshop in Bromley. I was already very familiar with the story of how and why Ford had chosen Eric Broadley to help design the GT40.

In truth, when studying the GT40 itself, it doesnt take long to see that, apart from the chassis being made of steel, the car was very much a Mark II version of Lolas Mark VI sports-prototype, sharing the same mid-engine position, the Ford V8 engine, and even the somewhat-lacking Colotti transaxle.

Im lucky that, having been around during this period, and always being racing car mad, I took a very keen interest in everything that was going on in the racing world in the 1960s, and had more than a passing interest in exactly who was doing what with what or even who

The books that I used for research are as follows, in alphabetical order:

Can-Am by Pete Lyons

Daring Drivers, Deadly Tracks by Brian Redman

Ford: The Dust and the Glory by Leo Levine

Forghieri on Ferrari by Mauro Forghieri

Go like Hell by A J Baime

Hobbo by David Hobbs and Steve Matchett

Lola T70, The Design, Development and Racing History by John Starkey and Franco Varani

Racing in the Rain by John Horsman, Chief Engineer at JWAE

That Certain Sound By John Wyer, head of FAV, then JWAE

The Anatomy and Development of the Sports Prototype Racing Car by Ian Bamsey

The Unfair Advantage by Mark Donohue, Driver

Foreword

Enzo Ferrari probably had no idea what he would start in 1962 when he put out tentative feelers through a third party to Ford in Dearborn, Michigan, to see if it might be interested in a collaboration.

To Ford, this meant that Ferrari was interested in selling his prestigious company to Ford; not what Ferrari had in mind. Yes, he was willing to sell that part of his company that made street cars, but he was not willing to sell the part that made and ran his racecars.

Enzo probably never foresaw just how upset Henry Ford II would be when he found his offer to Ferrari rebuffed; indeed, in the great scheme of things Ferrari may have been reaching out to Ford to elicit help from Fiat, which sat up, took notice and shortly thereafter came to Ferraris aid.

Ford had been involved in USAC Indianapolis oval track type events and also in NASCAR. In Europe it was not so involved, although Lotus entry in the Indianapolis 500 saw Ford supplying Lotus with engines: initially in the shape of an aluminum version of the V8 engine that went in the Ford Fairlane car, and then with a purpose-built four camshaft V8 engine.

In 1963, when the order went out from Henry Ford II to build a sports-prototype car that would beat Ferrari at the Le Mans 24 Hours, no such vehicle existed, and there was a mad scramble by Ford executives and their engineers to design and build a car that would embarrass Ferrari on a race track it had virtually made its own over the past few years.

This is the story of what transpired

John Starkey

Chapter

A successful team is born by a succession of people coming together at the right time. Such a team came together to win the Le Mans 24 Hour race in 1966: that of Ford. One of the unsung heroes of the Ford works team was Ken Miles.

Ken had been born on November 1 1918 into a working-class family in Sutton Coldfield, near the city of Birmingham in England. When he was 15 he tried to run away to America, but failed in his attempt. As he liked cars, he became an apprentice to the Wolseley Motor Car Company in Coventry. At that point in the 1930s, the company was producing middle-class cars for middle-class people, and Ken was sent to technical college in Birmingham to study and learn engineering.

Ken Miles, (left) and Lloyd Ruby, seen here after winning the Sebring 12 Hours race, held in March 1966.

(Courtesy Historic Images)

In September 1939 the Second World War broke out and Ken enlisted in the army. Due to his mechanical experience, he was swiftly moved to the Royal Tank Regiment and promoted to Sergeant. He became a tank commander and survived the war. Ken was 26 when the war ended, and he wanted nothing more than to be a racing driver. Unfortunately, he did not have the means to achieve this.

Undaunted, Ken fitted a Ford V8-60 engine in an old Frazer Nash chassis, and won some local hillclimbs and club races. He also tried building front wheel drive F3 cars but, by 1951, his money had run out and he was broke. Luckily, his friend, John Beasley, also from Sutton Coldfield, managed to get him a job in California as a service manager.

The Gough Company was a distributor for MGs, and realized that racing helped sell cars. Ken designed and built his first racing car with the aid of friends after a year of racing the stock MG TD cars: he called it the R1.

The R1 had a chassis made of steel tubing. Steering was by rack and pinion from a Morris Minor, and front suspension springing was by torsion bars. The rear suspension came from an MG TC, and the engine was from an MG TD. The skimpy bodywork was in aluminum.

Driving the R1, Ken Miles won many races in 1952. For 1954, Ken designed and built a lighter and more powerful car, which came to be known as the Flying Shingle. Ken left Goughs shop and moved to Clem Atwaters MG and Austin Healey shop, which was in the San Fernando Valley. Here, he set up his own shop, specializing in race car preparation.