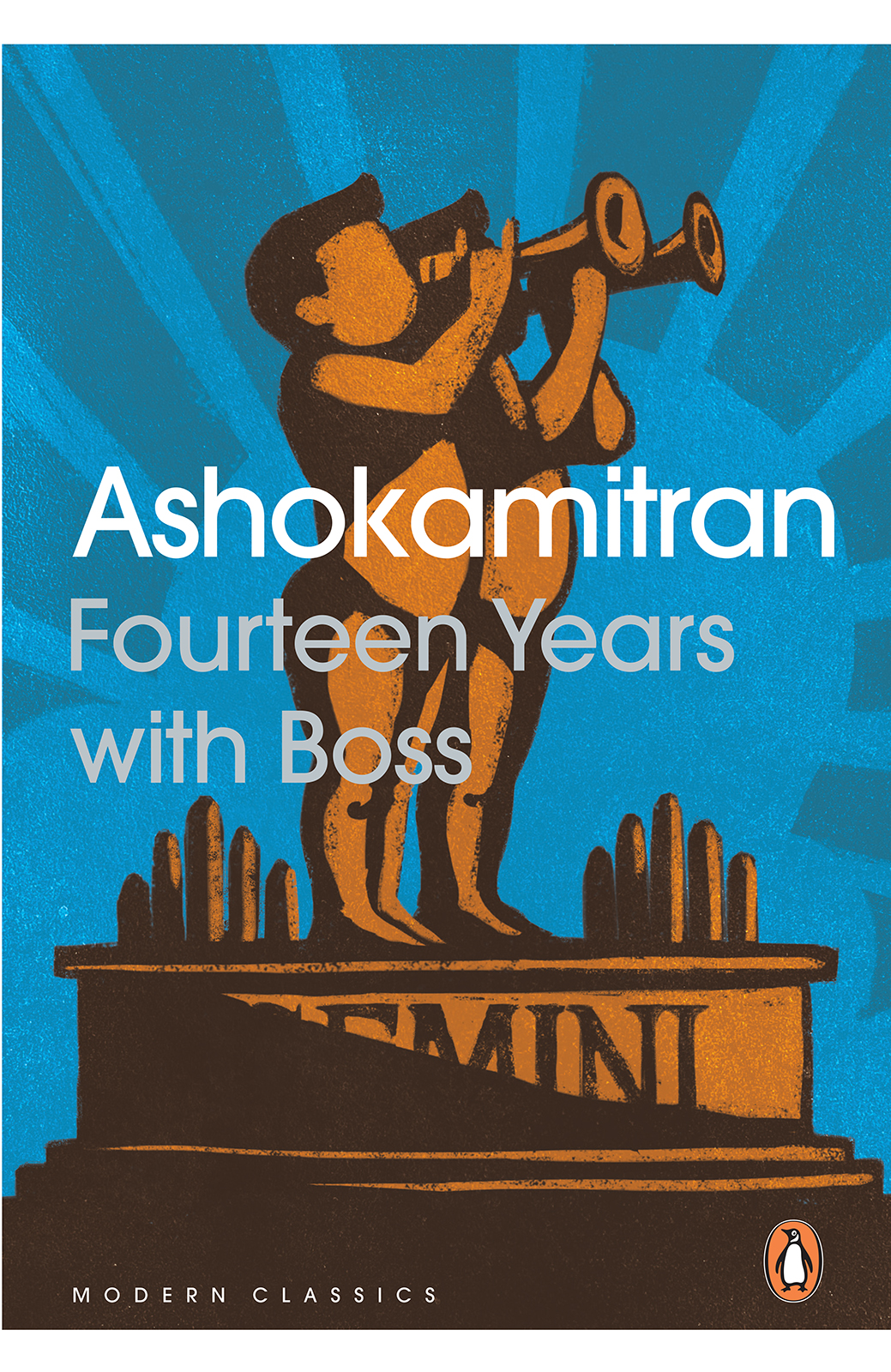

ASHOKAMITRAN, born in 1931 in Secunderabad, is one of the most distinguished contemporary Indian writers. In a prolific career that began in 1955, he has written over 250 short stories along with two dozen novels and novellas, in addition to a steady output of columns, essays and book reviews, earning him a central place in post-Independence Tamil literature. His work has been translated into many Indian and European languages. Five major novels as well as four collections of short fiction from his oeuvre are available in English translation. His years of rich and diverse contribution to Tamil literature have brought him many honours, including the Sahitya Akademi Award (1996). Ashokamitran lives and works in Chennai.

Introduction

I was twenty when I came across an issue of the Illustrated Weekly of India containing, among a bunch of sterling reading material, an article titled The Great Dream Bazaar by Ashokamitran. It was actually the first of a series of articles and at that time not only those in Tamil Nadu but readers in other parts of India as well keenly looked forward to successive instalments. The articles contained a pleasantly unpredictable sequence of events and details (like an English poet in a Madras studio). Of course, at that time I did not discern the artistic and stylistic aspects of the pieces but my friends, relatives and I were excited that what we knew about films hazily and what we did not know at all, was issuing out of the articles in an exceedingly informative and entertaining manner.

It was the year 1984 and Tamil Nadu had outgrown the MGRSivaji Ganesan syndrome and was gradually settling down to another pair, KamalahasanRajinikanth. Kamal Hasaan was Kamalahasan in those days. In the north, Rajesh Khanna had given way to the tall phenomenon called Amitabh Bachchan. A film society movement was flourishing in Madras and though my generation listened to Ilayarajas film songs and watched Kamalahasans films, we worshipped Kurosawa and Fellini. A separate genre of films known as the art film had come about with its votaries in Aravindan, Ritwik Ghatak, Kumar Shahani and Mani Kaul. There was the middle cinema, or the parallel cinema, headed by Basu Bhattacharya, Shyam Benegal and others. Satyajit Ray had created his great Charulata and Sippys Sholay was still drawing crowds. In such an atmosphere of abundance and variety, The Great Dream Bazaar (which I knew was the editors title and that the writer had called it My Years with Boss) made reflecting on Indian films and movie business an intellectual pursuit. The films themselves may not be imposingly great but the panorama of the entire film movement in the context of prevailing sociological, political and cultural forces of India made them a challenging and highly rewarding field of study. The articles also made one more tolerant towards popular cinema. There must be a tiny bit of truth to make hundreds of thousands of filmgoers spend their hard-earned money and sit through the film in a dark, uncomfortable hall for three hours. When that tiny bit of truth is out of sync, the film is rejected mercilessly.

In the Upanishads there is a discussion between a guru and his disciple about a particular daily ritual. The guru had said that the ritual performed three times a day was valueless as far as mukti, or freedom, was concerned but still had to be performed. Naturally, the disciple asks why. The guru replied that at least while performing the ritual one is protected from accumulating harmful karma. The history of films is now important not only to film scholars but to all thinking men and women with a concern for people and society. Many histories are straightforward narratives of events in sequence. Very often mere chronology leaves one unconvinced. But if the historian is able to capture the life and breath of events and make us believe that those men and women really existed, then history becomes meaningful. It is this liveliness and vivacity that makes Fourteen Years with Boss a brief but special book of history.

In Ashokamitrans fiction, human beings are written about as human beings with all their failings and shortcomings but still presented with dignity and earnestness. This book is vintage Ashokamitran. In the growing body of literature on Indian films, Fourteen Years with Boss is sure to find a choice place.

Hyderabad,

T. RAVISHANKAR

15 July 2010

1

My Fathers Friend

A hundred years ago, in the Nizams Hyderabad, people built palaces even if it was a single-room house. However small the actual living place was, the palace had a wide patio and a broad veranda in the front. The veranda was where guests were received; street vendors lowered their baskets to help the resident pick and choose vegetables and fruits, ice cream was bought and eaten, newspapers browsed, and overnight guests accommodated with pillows and blankets to sleep off the night. Percys Hotel, considered the best in Secunderabad, in 1940, couldnt help but look like a palace. With not much room in the front, there was a portico and broad verandas on all four sides. Tall, thin pillars delicately connected at the top by thin arches. Tall doors and a very high ceiling. The residents were provided with a table fan, table light and cot with a mosquito net. The view from the front rooms was enchanting. One saw the racecourse which had an exquisite pavilion. There were very few vehicles in the city so the hotel did not need much parking space. If one had keen eyes he could see the resident in the room, which was not too far from the road, Alexandria Road in this case. It was in one such room in Percys that I first saw the Boss along with my father.

S.S. Vasan, the Boss, had been a kind of salesman right from his teens. He sold small booklets and timetables. After a while he wrote books himself which he sold without claiming to be an author. He produced a truly voluminous book called 500 Ways to Start Small Businesses. I do not know how many put his lessons to practice but the book had no second edition and so no one could trace the author if anything went wrong or right. Then he wrote another voluminous book titled Kudumba Vinotha Kathaikal (strange stories that have happened within the family). He had a postbox and started a mail-order business selling bits of inexpensive but attractive articles, like a pistol which did not require a licence, hand-held spring articles for self-defence, etc. And he would send them with a box of pins with a claim that a thousand articles had been shipped for a rupee. When a tottering monthly magazine came his way, he bought it with all the money he hadabout three hundred rupees. Since he was himself a writer, he managed to get a band of talented but unpublished writers and embarked on journalism with all the enthusiasm possible. He made the magazine a totally error-free compilation of short pieces of various kindsfiction, reportage, current affairs, parodies, pen portraits and jokes. It will appear now that Ronald Ross of the